Francis Al˙s: A Story of Deception at MoMA

Nancy and I had the

great pleasure this past Tuesday evening to see an

opening preview of Francis Al˙s: A Story of Deception at MoMA. It is a truly fabulous exhibition,

and I recommend it to your most highly:

Francis Al˙s: A

Story of Deception

May 8–August 1, 2011

Sixth floor

Francis Al˙s

was born in

As you might guess, I do not

typically like video art; but Francis's style of work is a creative expression

all its own. His videos are beautiful, subtle, riveting, humorous, and

entertaining. Consider one of the first great examples in the MoMA

show, Cuento Patrióricos (Patriotic Tales)

(Mexico City, 1997; done with Rafael Ortega). It

is a 24 minute black and white video, shot from a high vantage

point, of an empty square with a flag pole in the center of

it. Francis enters from the side, leading a sheep behind him, and

begins to walk in a large oval path around the flag pole. One-by-one,

individual sheep enter from outside the side of the frame and begin to form a

single-file procession behind Francis, eventually forming an orderly line

8 or 10 strong behind him. At some point, Francis catches up with the end

of the procession, and begins to follow rather than lead the column.

Eventually, one at a time the sheep wander off from the line. It is an

absorbing, fun piece to watch: as with so many examples of Francis's work,

watching it brings a smile to my face—intensified in this instance by the comic

movement style of the sheep and the quiet absurdity of the action. The

filmed image is itself quite beautiful, and its composition is wonderfully

satisfying. It also becomes mesmerizing to watch. Just on this

level alone, the piece is totally successful as an artistic experience.

But then one starts to have feelings about the whole idea of

"sheep"—and about the "following" that is so essential to

what is going on; and then one is confronted with the reversal of the following

and the followed, and all that is evoked therein. Only after all that one

may become aware of the various levels of political implication and

reference. In Cuento Patrióricos, it turns out that there is a very

specific political premise underlying the work, which I was not aware of

until reading the description (which, as typical for me, I did not do until after

watching the video):

This

fiction refers to a key event in the student protests against Mexico's

government that occurred in 1968: on 28 August 1968 of that year,

thousands of civil servants were brought to the Zócalo

or main square of Mexico City to demonstrate in favor of the government,

claiming that the students had defiled the national symbols by raising the Red

and Black flag on the Zócalo pole. But in

a spontaneous gesture of rebellion, the bureaucrats turned their backs on the

official tribute and began to bleat like a vast flock of sheep, forcing the

authorities to disperse them with armored tanks and infantry. [quoted from the catalogue for the show]

It is not in any way necessary to

know this specific historical/political reference to appreciate the piece (and

it is one of my main objections to conceptual art that it often requires such

an explanation in order to be appreciated), although it does adds a dimension

and a depth when you know. What is unavoidable in Francis Al˙s's work is the sense of meaning that goes deeper than

the straightforward significance of the events depicted. Often this sense

of meaning is quite covert, and sometimes it operates only on an unconscious

level; sometimes it is closer to the surface; but it never interferes with the

more immediate artistic appreciation of the works. Interestingly, this

gives a certain politically subversive quality to Francis's art.

Francis was chosen for the Global

Cities exhibition in part because of his extensive interest in cities and urban

issues—and, of course, in even larger part because of the artistic excellence

and artistic power and evocativeness of his urban images. In some of his

works, these urban issues are far more directly in evidence. Paradox

of Praxis I (Sometimes Doing Something Leads to Nothing)

(Mexico City, 1997; 5 minutes, color; a version of which [Sometimes Making

Something Leads to Nothing] available online at www.francisalys.com/public/hielo.html),

Francis pushes a huge block of ice around the center of Mexico City for hours

until it finally melts away. Against the continuous urban backdrop of the

streets of city's poor neighborhoods, one begins to sense the huge exertion and

endless monotony of this physical labor, which, in the end, produces neither

results nor rewards. As usual, there is a bemused humor one feels in

watching the action unfold; and yet there is also an underlying awareness of an

important—albeit subtle—meaning. In Rehearsal I (El Ensayo) (Tijuana, 1999-2001; 29 minutes, color),

filmed on the US-Mexico border, an old VW Beetle heads up a steep little hill

on a dirt road through an arid village. There is a soundtrack

playing of a brass band rehearsing, and the driver has been given the following

instructions:

-While

the musicians play, the car goes uphill.

-When the musicians lose track and pause, the car stops.

-While the musicians are tuning their instruments, the car rolls back downhill.

Even without knowing the mechanics

of what is transpiring, this Keystone Kops' version of a Sisyphean process is

wonderfully comic—and the music of the brass band adds to the overall

humorous effect. And yet, set as it is in a poor Latin American

neighborhood, there is an ever-present echo of the  frustrations

of the economic experience of that region.

frustrations

of the economic experience of that region.

The one other video work I want to

mention is his  documentation, both in color; the photographic

documentation of which is available online at www.francisalys.com/public/cuandolafe.html).

The premise here is "500 volunteers equipped with shovels and asked to form

a single line in order to displace by 10 cm a 500 m-long sand dune from its

original position." This long line of people,

shoveling sand in unison on this dune outside of

documentation, both in color; the photographic

documentation of which is available online at www.francisalys.com/public/cuandolafe.html).

The premise here is "500 volunteers equipped with shovels and asked to form

a single line in order to displace by 10 cm a 500 m-long sand dune from its

original position." This long line of people,

shoveling sand in unison on this dune outside of

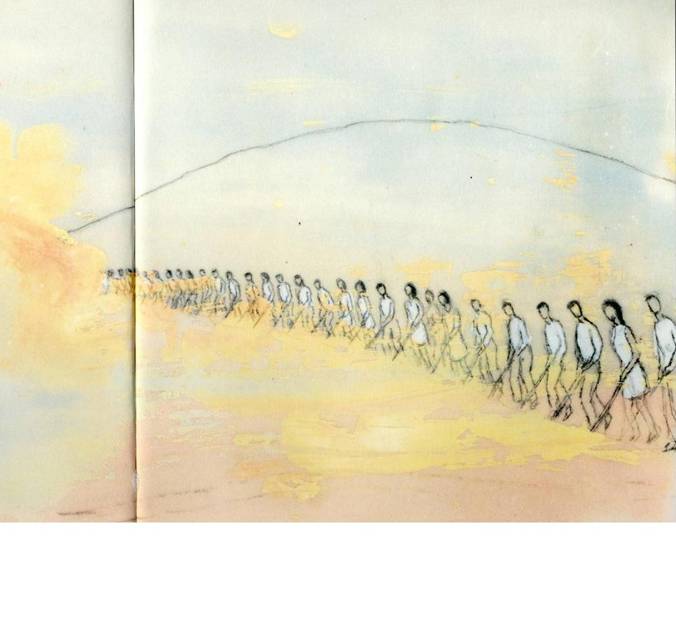

I shall use the opportunity of

discussing When Faith Moves Mountains to mention that

along with Francis Al˙s's video works, there are many

paintings, drawings, and sketches—many with written instructions or

comments—which accompany the videos (like the one at the right, which is a

study for When Faith Moves Mountains, and which I have

shamelessly stolen from the catalogue of the exhibition), and some that are

projects in their own right (like the series Lynchings

(Linchados) [2006; Paintings: Oil and

collage on canvas on wood]). Francis is an extremely talented

painter and draftsman, in addition to being a brilliant video artist.

One of my favorite things in the

show is his Le Temps du sommeil

(1996- present), which consists of 111 small paintings done in oil,

encaustic, crayon, and collage on wood. This series represents an

evolving visual diary of Francis's creative journey, and he paints,

over-lays, and paints over each of the component pieces with images from

and references to the work he has done.

There is also a wonderful piece entitled Song for Lupita (Mańana) (1998; an installation with projected animation, record player, and vinyl record). A long 16 mm film loop, extending 20 feet up to the high ceiling of the gallery, runs continuously through a projector which projects onto a frosted glass screen the simple, black and white outline drawing of a woman pouring a bright, aqua-colored liquid back and forth between two glasses. The visual image plays against the song on the record player, which speaks of "putting off the task until a 'tomorrow' that loops eternally."

Finally there is one totally

unusual visual piece, Tornado (Milpa

Alta, 2000-2010; 55 minutes). In this rather bizarre video, Francis

actually takes his camera and himself—and us with him—into the tornadoes he has

been chasing. He sometimes misses, he sometimes succeed;

but it is a frighteningly tense struggle. Here is the catalogue's

description:

"Ever tried. Ever Failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better."

(Samuel Beckett, Worstward Ho, 1983)

Over the

last decade Al˙s made recurrent trips to the

highlands south of

There is a brief but very suggestive clip from this work on MoMA's website for the exhibition: www.moma.org/visit/calendar/exhibitions/1104

So, the short story is, go to this wonderful exhibit! It is full of things that will please, surprise, and amaze you.

![]()