If you at all can, get yourself

to the

George Braque: Pioneer of Modernism show at Acquavella Galleries in New York. This amazing show closes on 30 November, and it is a must-see! I was just able to get there this past

weekend (it has been up since the middle of October), and I was so glad I did not miss it.

Georges Braque

Pioneer

of Modernism

Oct 12 - Nov 30, 2011

Acquavella Galleries, Inc.

18 East 79th Street (between

Madison and Fifth Avenues)

Open Monday-Saturday,

10am to 5pm

212-734-6300

While there have

been a number of recent major shows in which Braque has figured prominently,

there has not been a retrospective in of his work in New York in more than  twenty

years. I am a great fan, and therefore I

was very much looking forward to this show.

It was curated for William Acquavella’s

elegant East 79th Street gallery by Dieter Buchhart,

and it contains 41 wonderful paintings and papiers collés by this master spanning the years from 1906 to the

mid-1950s. That this show is being

mounted by a private gallery is even more impressive, and it contains several

absolutely fabulous pieces from private collections—although it also contains

works on loan from many the major museums (The Met and MoMA

in New York, the Phillips in Washington, the Pompidou Center in Paris, the Tate

in London, the Pinakotek in Munich, the Kröller-Müller in The Netherlands, et al.).

twenty

years. I am a great fan, and therefore I

was very much looking forward to this show.

It was curated for William Acquavella’s

elegant East 79th Street gallery by Dieter Buchhart,

and it contains 41 wonderful paintings and papiers collés by this master spanning the years from 1906 to the

mid-1950s. That this show is being

mounted by a private gallery is even more impressive, and it contains several

absolutely fabulous pieces from private collections—although it also contains

works on loan from many the major museums (The Met and MoMA

in New York, the Phillips in Washington, the Pompidou Center in Paris, the Tate

in London, the Pinakotek in Munich, the Kröller-Müller in The Netherlands, et al.).

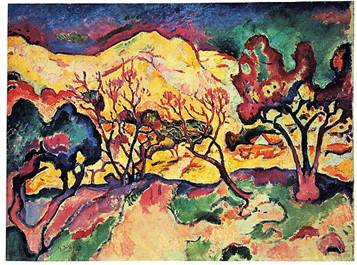

Nancy and I are

always a bit surprised when we come across Braque’s Fauve paintings (from the

first decade of the 2oth century), and some always strike us as deeply

wonderful. George Braque: Pioneer of

Modernism has five  such

paintings, although most of them are not of the sublime quality his works of

this period often achieves. One

particularly successful one, however, is his1906 Landscape

at L’Estaque (above, at right; oil on canvas, 23 ⅝ x 31 ⅞ inches).

such

paintings, although most of them are not of the sublime quality his works of

this period often achieves. One

particularly successful one, however, is his1906 Landscape

at L’Estaque (above, at right; oil on canvas, 23 ⅝ x 31 ⅞ inches).

Among the most interesting of the early paintings is his 1907 oil on canvas, Houses at L’Estaque. (Unfortunately, I cannot locate an

image of this particular painting. I

include at the left, a much less interesting 1908 example from this

series.) This one, from a private

collection, is part of a series Braque did in 1907-8, in which the profound

influence of Cézanne is clear—as is what it  portends for

the development of Cubism, which lies just ahead. Picasso, of course, had also been inspired by

Cézanne in his slightly earlier creation of the pivotal 1907masterpiece, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, which, in

fact, drew Braque to him and into their mutual creation and exploration of Cubism. By the

time Braque gets to his 1909 Harbor

(at right; oil on canvas, 16 x 19 inches), his Cubist style is clearly in

evidence. Heresy though it may be, I

generally prefer Braque’s Cubist works to the similar ones done by

Picasso. Unfortunately, the examples of

these early Cubist paintings in this exhibit are not among

portends for

the development of Cubism, which lies just ahead. Picasso, of course, had also been inspired by

Cézanne in his slightly earlier creation of the pivotal 1907masterpiece, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, which, in

fact, drew Braque to him and into their mutual creation and exploration of Cubism. By the

time Braque gets to his 1909 Harbor

(at right; oil on canvas, 16 x 19 inches), his Cubist style is clearly in

evidence. Heresy though it may be, I

generally prefer Braque’s Cubist works to the similar ones done by

Picasso. Unfortunately, the examples of

these early Cubist paintings in this exhibit are not among  Braque’s

best—although they are still quite spectacular.

Braque’s

best—although they are still quite spectacular.

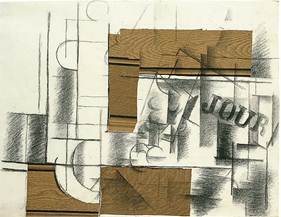

The fabulous

1912 Glass, Bottle and Newspaper

(at left; charcoal and faux-bois wallpaper on paper, 18 ⅞ x 24 ⅜

inches), like the 1913 Glass and

Tobacco (one of my very favorites, for which I cannot locate an image)

and the 1914 Bottle, Newspaper, Pipe,

and Glass (at right; cardboard, pasted and painted papers, newspaper,

charcoal on  paper, 18 7/8 x 25 1/4 inches), is from a private collection, and an

enormous treat. All of the paintings and

papiers collés in the

exhibit form this period leading up to the War are extraordinary, and my

very favorite things in the show.

paper, 18 7/8 x 25 1/4 inches), is from a private collection, and an

enormous treat. All of the paintings and

papiers collés in the

exhibit form this period leading up to the War are extraordinary, and my

very favorite things in the show.

The second half of the show, which is

found in the two first floor rooms of the Aquavella Galeries (the show begins in the front room of the second

floor, continuing on the rear room; this pattern is continued on the first

floor), consists of his post-War works.

My favorites form room three where his oils on canvas from the end of

the 1910s and 1020s: the 1919 Compotier,

and, even more so the 1918-9 Black

Guitar; and the Cézanne reprise

in the form of the lovely 1925 Lemon,

Bananas, Plums, Glass.

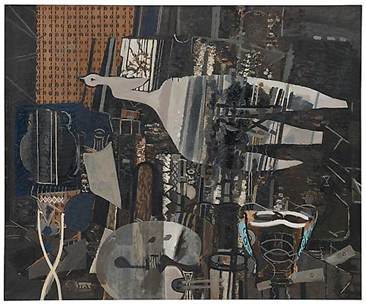

George Braque: Pioneer of Modernism culminates in the final room with paintings he did

in the 1930s, 40s, and 50s—and these are the paintings the show has been

building  toward. While they are incredibly interesting, I do

not like his work from this period nearly as much as I do his earlier

work. His Billiard Table paintings are far and away the most

interesting of the lot. Both the 1944-5

(oil with sand and charcoal on canvas; no image) and 1945 (at left; oil and

sand on canvas, 35 x 45 ¾ inches) are very satisfying.

toward. While they are incredibly interesting, I do

not like his work from this period nearly as much as I do his earlier

work. His Billiard Table paintings are far and away the most

interesting of the lot. Both the 1944-5

(oil with sand and charcoal on canvas; no image) and 1945 (at left; oil and

sand on canvas, 35 x 45 ¾ inches) are very satisfying.

Reminiscent of a number of other

unusual—and predominantly dark—works Braque did late in life that we have loved

when we have come across them, his

Studio V from 1949–50 (at right; oil on canvas, 57 ⅞ x 69 ½

inches) is an exciting late painting.

A lovely 200 page hardcover catalogue for this exhibition has been published by the gallery, and it is well-worth purchasing. In addition to excellent, large, full-color reproductions of each of the works in the show, it contains essays by Dieter Buchhart (the curator), Isabelle Monod-Fontaine and Richard Shiff.

There has been considerable press about

this show, and I include below a piece from the NY Times of 13 October by Roberta Smith.

Meanwhile…get there to see it before it

closes! It is a great show.

The Other Father of Cubism

By ROBERTA

SMITH

Published: October 13, 2011

The Acquavella

Galleries’ splendid Georges Braque exhibition is a 42-gun salute to this

pioneering French Modernist. The first large Braque survey to be staged in New

York in more than 20 years, it musters a vigorous if compressed account of more

than five decades of art making, with 42 paintings and collages, almost all

top-notch. More than half have been borrowed from American and European

museums; the rest come from private collections and in several cases have not

been on public display in quite some time.

This show means to establish

Braque’s importance in a town where Picasso, his flamboyant partner in the

development of Cubism, which set so much of 20th-century art in motion, looms

very large. How large? The Museum of Modern Art’s Web site places the number of

works by Braque in its collection at 31. The number by Picasso (sitting down?)

is 1,211. Picasso was inordinately talented and important, but 40 times more so

than Braque?

Organized by Dieter Buchhart, an Austrian critic, art historian and independent

curator, the Acquavella show rarely lets down its

guard. In nearly every effort Braque is at his most elaborate and ambitious,

from his slightly over-heated Fauvist efforts of 1906-7 to his opulent still lifes of the 1930s and ’40s and his crowded and shadowy studio

interiors of the 1950s. In the show’s middle portion, of course, we see Braque

the Cubist.

His collaboration with

Picasso began in earnest after he first saw the groundbreaking “Demoiselles d’Avignon” in Picasso’s studio in late 1907. But by then

Braque was already alert to the implications of Cézanne’s angled brush strokes

and multiple perspectives and the tantalizing way they destabilized painting’s

traditional unities of form and space, and therefore time.

Braque would later say that

he and Picasso were roped together like mountaineers in their invention of

Cubism. Picasso saw things a bit differently, referring to Braque as “ma

femme,” or “my wife.” Either way, their intensely close collaboration lasted

until the fall of 1914, when Braque enlisted in the French Army early in World

War I. They went their separate ways and, like many divorced couples, rarely

spoke of each other.

They could not have been more

different. Braque’s father was a house painter and decorator who made sure that

his son learned the artisanal skills of his trade; Picasso’s was an academic

painter who gave him drawing lessons.

Braque was tall, reticent,

methodical and quintessentially French, with all that that implies in terms of

reason and balance. He dressed in a neat, discreetly dandyish way, was

intensely private, remained married to the same woman all his life and worked

in the same studio from 1926 until his death in 1963, at 81.

Picasso was short, volatile,

charismatic and innately messy and bohemian, as well as Spanish. He changed

houses, companions and painting styles at regular, closely watched intervals

and did more than his share to establish the persona of the modern artist as

celebrity, complete with entourage.

This show confirms that

Braque may have separated from Picasso, but he never really divorced Cubism,

which he developed, as he later said, “above all to

put painting within the reach of my own gifts.” These gifts did not include,

for example, Picasso’s genius for drawing or for psychological expression conveyed

by continually metamorphosing faces and figures.

Braque was never much for

figures; his abiding, even monogamous, interest lay in the complex act of

perceiving and painting accumulations of objects, in his studio. Cubism gave

him a system, a way of dissecting, enhancing and complicating reality that he

cultivated for the rest of his life.

The show gives a wonderful

account of Braque’s contribution to Cubism and of the way that his early

training in his father’s trade — which included sign painting and the painting

of imitation wood and marble — figured increasingly in this project, and

throughout his career. It was clearly the basis for his interest in what he

called the “tactile” or “manual” space of a painting.

In this spirit, his

innovations included the contradictory practices of painting flatness-inducing

letters and words, and depth-creating trompe l’oeil nails and other details

(with shadows) that so confound Cubist space. Both float among the tensile

scaffoldings and eddies of brush strokes in “The

Mantelpiece,” a shimmering, mostly white and gray Analytic Cubist painting from

1911 that is also strewn with fragmented scrolls that evoke violins and

architectural molding.

It was also Braque who began

to emphasize physical surface by adding sand, sawdust and metal shavings to his

paint and gluing pieces of wallpaper and newsprint to his drawings, inventing

the refined form of collage known as papier collé (glued paper). The papiers collés here include the delicate “Glass, Bottle and

Newspaper,” of 1912, and the wonderfully blunt “Bottle and Musical

Instruments,” with its corrugated-cardboard decanter, from 1918. Wood-grain

wallpapers would inspire him to resuscitate his wood-grain-painting skills,

another habit that you can follow through the later pieces.

It is actually the less

familiar, later work in this show’s second half that is most gripping, as

Braque continues on alone with Cubism, expanding and filling it out, making its

intersecting forms and transparencies and free-range details more legible and

consequently more engaging and seductive.

In the 1935 still life “The Guéridon,” with its eponymous three-legged, oval-topped

table stacked with fruit, glass vessels and a hint of a newspaper, we get lost

in the carefully built composition; the overlapping, papier-collé-like rectangles of color; the contrast between

outlines and full-bodied forms; and the odd decorative details, like the

zigzags accompanied by trios of dots that wander across the wall, but also

float in front of it, pulled forward by an unexpected rectangle of rather real

light.

From the next year, the

tilted still life of “The Mauve Tablecloth” is accompanied by a golden ghost

chair and disrupted by another unquiet background, this one of deliberately

awkward marbleized panels.

These are mysteriously

beautiful, oddly ego-free works. John Russell, writing in The New York Times,

aptly described Braque as “an unemphatic genius.” In

his still lifes and also his studio interiors, his

elaborate physical processes and layers of pattern and shadow slow down time,

but so does the way he disappears into the work, which is personal without

being burdened by personality. Nothing gets in our way as we wander through

these elaborate compositions, warming to the quiet intelligence and patient craft

with which they were made, and slipping into their deep, meditative

strangeness.

In the catalog’s essays,

written by the art historians Isabelle Monod-Fontaine and Richard Shiff, as well as Mr. Buchhart,

several things illuminate these works: Braque’s use of the word “hallucination”

and his interest in Zen, and above all his stated preference, as quoted by Mr. Shiff, for “the lyricism that derives wholly from the

means.” Braque was no Picasso, but his art after Picasso, while mysterious,

should be less of a mystery to us. This show, with its succinct presentation of

high points, erodes that obscurity.