There are two shows in LA worth knowing about,

both at LACMA:

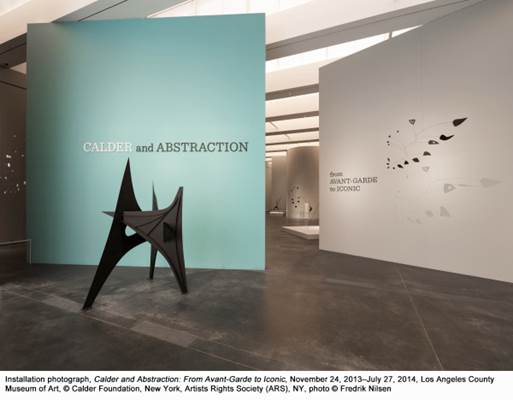

CALDER

AND ABSTRACTION: FROM AVANT-GARDE TO ICONIC

and SEE

THE LIGHT—PHOTOGRAPHY, PERCEPTION, COGNITION: THE MARJORIE AND LEONARD VERNON

COLLECTION. Both are described below.

CALDER

AND ABSTRACTION: FROM AVANT-GARDE TO ICONIC

There is a great exhibition of the mobiles and

stabiles of Alexander Calder in the Resnick Pavilion at LACMA

(The Los Angeles County Museum of Art) that

is being shown until 27 July 2014. It was a pleasant surprise to see just how unexpectedly wonderful this

exhibition, CALDER

AND ABSTRACTION: FROM AVANT-GARDE TO ICONIC, actually

was.

Most everyone is familiar with—and most of us are extremely

fond of—Calder’s marvelous creations;

but this show has some particularly spectacular pieces, and everything is

amazingly well-displayed. We were especially

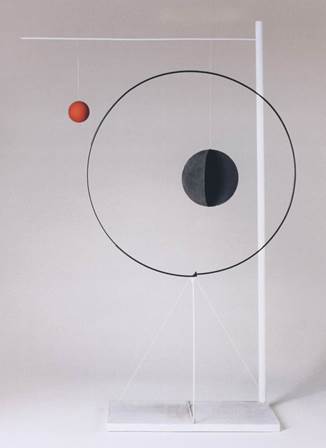

pleased to see some of his early works from 1931, in which he was clearly doing

what he described as “drawing in three dimensions”:

Croisiére. 1931, 37 x 23 x 23

Object

with Red Ball, 1931, 61 ¾ x 38 ½ x

12 ¼

As Jed Perl

notes in his essay “Sensibility and Science” in the impressive catalogue for

the show (eds., Stephanie Barron and

Lisa Gabrielle Mark, DelMonico

Books), Calder “said that it was a

visit to Piet Mondrian’s studio in 1930 that provoked his dramatic turn to

abstraction.” (p. 41) Stephanie Barron (in

her essay “Time, Space, and Moving Forms: Alexander Calder—Beyond the Beautiful”

in the catalogue) quotes Calder as saying after that visit to Mondrian’s

studio:

“The visit gave me a

shock… Though I had heard the word ‘modern’ before, I did not consciously know

or feel the term ‘abstract.’ So now, at thirty-two, I wanted to paint and work

in the abstract.”

He said, “I was

particularly impressed by some rectangles of color he had tacked on his wall in

a pattern after his nature. I told him I

would like to make them oscillate—he objected.

I went home and tried to paint abstractly—but in two weeks was back

again among plastic materials.” (p. 17)

Barron also points out that “Calder would subsequently draw

his palette from Mondrian’s example as well, using black, white, red, and occasionally

blue and yellow.” (idem)

She notes that, “Art historian George

Baker, however, argues that Calder’s abstraction may owe more to the work of

Duchamp and Arp, as well as to Dada in general.” (pp. 17f) Barron

cites a well-known passage in Calder’s 1966 autobiography describing an interaction

in his studio with Duchamp:

I asked him what sort

of a name I could give these things, and he at once produced “Mobile.” In addition to something that moves, in

French it also means motive. (p. 18)

The exhibition, which was organized by Stephanie Barron, is particularly

beautifully displayed. The installation

was designed by Frank Gehry.

The curved walls and subtle colors set off the work to

maximum effect:

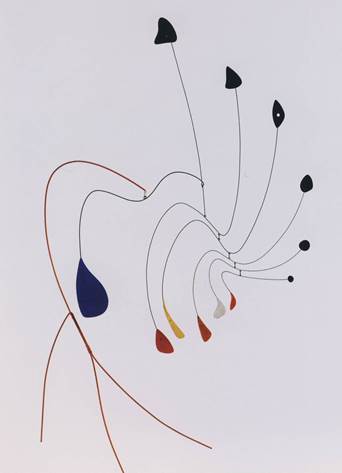

Another delicately beautiful and clearly feminine

piece we loved was

La

Demoiselle, 1939, 58 ½ x 21 x 29 ½

Stephanie

Barron, also in her essay

in the catalogue, notes the importance of Calder

having met Miró in 1928, and quotes Calder as having “admitted,

‘Well, the archeologists will tell you there’s a little bit of Miró in Calder and a little bit of Calder in Miró. (p. 17)’ ” Below is an odd

piece that clearly shows the influence of Calder’s

having met Miró:

Red

Panel, c.1938,

48 x 30 24

There are more photographs of the exhibit available on

the LACMA

website at www.flickr.com//photos/lacma/sets/72157638119901055/show/with/11088061416/. The following is the museum’s description of

the show:

One of the most important artists of the twentieth

century, Alexander Calder revolutionized modern sculpture. Calder and Abstraction: From

Avant-Garde to Iconic, with significant cooperation from the Calder

Foundation, explores the artist’s radical translation of French Surrealist

vocabulary into American vernacular. His most iconic works, coined mobiles by Marcel

Duchamp, are kinetic sculptures in which flat pieces of painted metal

connected by wire move delicately in the air, propelled by motors or air

currents. His later stabiles

are monumental structures, whose arching forms and massive steel planes

continue his engagement with dynamism and daring innovation. Although this will

be his first museum exhibition in Los Angeles, Calder holds a significant place

in LACMA’s history: the museum commissioned Three Quintains (Hello Girls) for

its opening in 1965. The installation was designed by architect Frank O. Gehry

Also in the Resnick Pavilion at LACMA:

SEE

THE LIGHT—PHOTOGRAPHY, PERCEPTION, COGNITION: THE

MARJORIE AND LEONARD VERNON COLLECTION

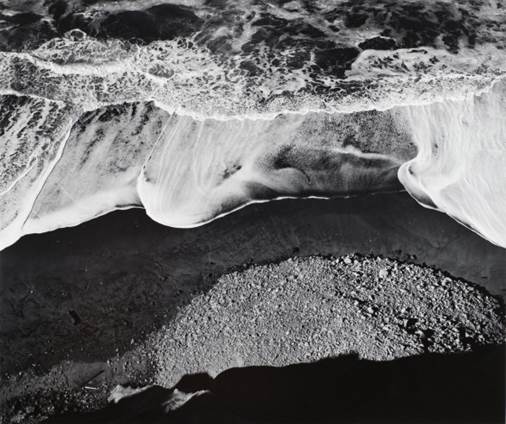

We had not even known this was there; but it is a wonderful collection of photographs by some of the very best photographers—and well-worth seeing. Here are a few beautiful examples:

Frederick H. Evans, A Sea Of Steps—Wells Cathedral,

1903

Walker Evans, Lake

City Bank, Indiana, c. 1930, Image:

4 ¾ x 3

7/8; Mount: 18 x 14; Mat: 18 x 14

And Surf Sequence by Ansel Adams, c. 1940 (printed

after 1972), Gelatin-silver prints, Images: 11 x 14, Mat: 16 x 20

Here is the museum’s description:

Los Angeles residents Marjorie and

Leonard Vernon began to collect photography in 1975, eventually building a

collection of some 3,600 photographs spanning the entire history of the medium.

In 2008 LACMA acquired the complete collection,

making it possible for the museum to represent photography’s full range and its

centrality in modern visual culture. This exhibition of 220 photographs from

the Vernon Collection takes a historical perspective, identifying parallels

between photography and vision science over time. The earliest commentaries on

photography, published at the moment of its invention in the late 1830s,

positioned the medium between art and science. As a scientific instrument, the

camera operates as an infallible eye, augmenting physiological vision; as an

artistic tool, it channels the imagination, recording creative vision. Much of

photography’s authority and fascination resides in its interdisciplinary

grounding. Whether we analyze it as a science or admire it as an art,

photography’s power may never be fully explained, but it will always offer

revelations about vision, perception, and cognition

![]()

Return to Dead Parrot homepage.