[Subsequent to this posting, I issued a CALL TO ACTION about this situation, which I ask that you read at www.rickrubens.com/JM-Action.htm, and I hope that you will consider lending your serious support to the efforts to rectify this gross miscarriage of justice and departure from reason. This is a great project, and it needs our help.]

When Nancy and I visited Jaipur (in the Rajasthan region of India) this past January, we were shown an amazingly wonderful example of a public-private partnership in the restoration of the Jal Mahal (“Water Palace”). Nevertheless, public-private partnerships have many bad possibilities, and there is a problematic aspect to this wonderful project.

“Public-private partnerships” have become the watchword of cities’ attempts to fund projects of late, ever since public coffers have increasingly become empty. There are many problems with such endeavors. My Urban Age program’s governance guru (and friend), Gerry Frug (from Harvard Law School), has at UA conferences fired volleys at the excessive fervor for such deals: once, at the Mumbai conference, he posed the questions, “In a public-private partnership, who represents the public?” and, “Can I see the partnership agreement?”; and, at the Istanbul conference, he more acerbically interjected, “I just want to remind everyone that graft is a well-known form of public-private partnership!” The most pernicious problem, however, is the temptation for cities to abdicate their responsibility through the use of such endeavor: while these arrangements often provide clever and effective answers to how to fund certain projects, it is only government that is capable of and has the direct responsibility to provide the most basic public realm facilities and services. The most essential issues of infrastructure, and the most basic of services (education being foremost among them) must be provided publically, as there is just not room for a profit margin to drive the process privately. Currently there is a pervasive tendency to obscure this reality by focusing on public-private partnership solutions as if they could provide ultimate answers to the problems of lack of public resources. Such arrangement can provide funding for specific projects; but they cannot substitute for the basic things government needs to provide.

The Jal Mahal project is a sterling example of a great and appropriate opportunity to solve a problem using a very creative public-private partnership. (But please read through to the end, as this story does not have a happy ending…at least, not yet.)

Early in the 17th century, Darbhawati River

was dammed to create the Man Sagar Lake. In

1727, with the decline of the Moghul Empire and its control over the region of

Rajasthan, the Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh made the bold move of moving his

capital out of the hilltop fortress of Amber, and establishing it in the city

of Jaipur which founded on the

plains to the south. (The story of this

incredible city and its magnificently successful urban plan is a subject for

another time. Suffice it to say for the

moment, it was based on the shastric principles of

the nine-unit mandala, with a geometric grid, and a geometric system of

subdivisions by secondary and tertiary streets, all in harmonious numerical

proportion, and all creating a comprehensible structure within which more

organic, informal growth and individuality could occur. An incredibly scholarly, insightful, and

riveting history of the creation of Jaipur can be found in Vibhuit Sachdev and Giles Tillotson’s Buliding Jaipur: The Making of an India City, 2002, Reaktion

Books, London.) By 1734, Jai Singh felt

the need for a retreat from the wonderful urban environment he had created, and

he built the floating palace of Jal Mahal in the midst of Man Sagar

Lake.

The Jal Mahal and its surrounding lake became the property of the

Rajasthan government after Independence, and both quickly sank into

disrepair. In the early 1960s, the city

of Jaipur began to discharge its growing volume of sewage directly into the

lake, and before long it became unbearably polluted. The situation was exacerbated by the fact

that in the dry season the lake often was dry.

The entire area became a festering, putrid wasteland. (A look in any guidebook for Jaipur will

include a warning to stay away from this site due to the stench and lack of

anything worth seeing. In the article

attached at the end of this piece, there are pictures of the lake and palace in

their pre-restoration state of decay/)

The Jal Mahal Resorts Pvt. Ltd. consortium, led

by Navratan Kothari, won the bid in 2004 to

rehabilitate the lake and restore the Jal Mahal. The deal was

that the consortium would finance all the restoration work in return for being

able to build two luxury hotels next to the lake. Architect

Rajeev Lunkad assembled an incredible team, including German engineer Harald Kraft (an expert on restoring manmade

lakes), historian Giles Tillotson (whose excellent book on Jaipur I referenced

above) to oversee the historic authenticity of the restoration, Vibhuti Sachdev

(co-author of that book on Jaipur) who curated the art, and anthropologist and

restoration expert Mitchell Abdul Karim Crites.

The results, which Nancy and I had

the unfortunately rare privilege to visit, are astounding! The consortium built a sewage treatment

facility and a vast wetland to handle the effluent; so now the lake is now

clean. Not only is there no smell, the

waters of the lake are now supporting all forms of aquatic life: fish are once again able to live in the lake

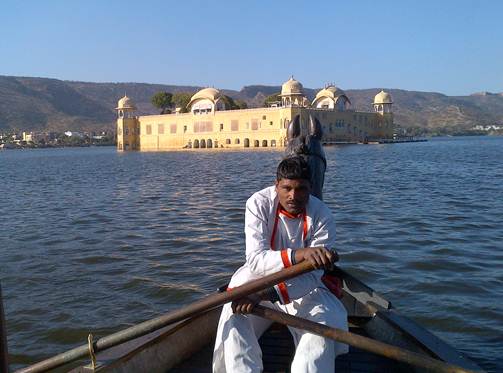

in such abundance that waterfowl have returned in droves to the area. (The photograph below is taken from one of

the beautiful, specially designed wooden boats to row tourists out to the Jal Mahal)

The rehabilitation of the lake,

alone, is an unbelievable achievement.

But the creative but historical restoration of the palace itself is breath

taking. It was lovingly and artistically

done.

Throughout the palace, gorgeous,

photographically enlarged artwork from the period adorns the walls, as this

detail, below, of a swimming scene:

But perhaps the most strikingly

beautiful aspect of the restoration was the creative approach to the roof

garden, the Chameli Bagh, where

more liberties were taken with period accuracy:

it was decided to fill it with fragrant white flowers from around Jaipur

(chamelis, champas and

white lotuses) and light it playfully.

At night it becomes a fantastic

wonderland.

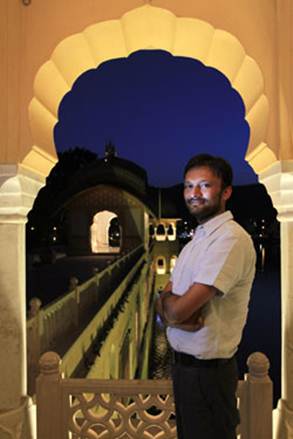

I wish the following picture,

taken as we were rowed back from several extraordinary hours spent savoring the

beauty and wonder of this project with Rajeev

Lunkad’s

associate, architect Gagan Sharma,

was the beautiful end to the story as it was the beautiful end to our visit:

Unfortunately, the consortium made

a major mistake: it rehabilitated the

lake and restored the palace before

building the hotels. In an epic instance

of corruption, malfeasance, greed, and stupidity, the consortium has been

enjoined from building the hotels (which, one should remember, were designed to

be the payoff for fronting the money to do the rehabilitation and

restoration). As the attached (below)

article, “Ruining

a Revival,” by Ravati Laul in Tehelka summarizes it:

Three petitioners took Navratan Kothari

to court, charging him with criminal conspiracy. Of cheating

and forging documents to snatch priceless heritage for private profit.

The police probed these allegations against this perceived heretic

three times, each time returning to the Rajasthan High Court without a smoking

gun. But the court wouldn’t take ‘no’ for an answer. It chided the police for

failing to see a larger conspiracy between Kothari and political actors, and on

16 November 2011, issued a non-bailable warrant

against him. Then, on 17 May this year, Chief Justice Arun

Mishra ruled that the work done by Kothari’s company be reversed. The nalas that had been diverted from the lake must be restored

to their former condition. In other words, the sewage nalas

were directed to be channelled back to the lake.

There was a warrant out for Kothari’s arrest, forcing him to flee the city;

until reprieve came on 25 May. That’s when the Supreme Court stayed the

Rajasthan High Court order, putting the question of Kothari’s criminal

culpability in pause mode till both sides of the case are heard.

The most incredible idea in all

this is the court’s insistence that the sewage be returned to the

now-unpolluted lake! I leave it to the

article to lay out for you the details of what is going on legally; but it is

truly shocking. The short story seems to

be that the BJP government is taking a swipe here at a Congress-initiated

project and the people associated with it, and making an underhanded grab for

the value that has been created in the process. Whatever the details, the

attempt to thwart, steal, and perhaps even undo the fabulous results of this

agreement that has achieved what it was supposed to accomplish is

reprehensible.

The article, which I most strongly

recommend that you read, concludes that the deeper problem is that, “India has

no legal framework for public-private partnerships.” Moreover, it points to the fact that if

India’s historical monuments are to be rehabilitated and saved, there will need

to be such public-private partnerships.

For now, the work has been halted. The Jal Mahal is not open to the public, and this outcome is mired in the corruption of the Indian legal system.

Here is the article which I recommend you read, I suspect with the same outrage that I have felt:

|

|

|

|

|

|

THE HERITAGE DEBATE

Ruining

a revival

The restoration of the Jal

Mahal palace in Jaipur under a public-private partnership

could have become the blueprint for saving our derelict heritage. But what

followed was a slew of petitions and a legal tangle that threatens to derail

similar projects all over the country. Revati Laul unravels the intriguing story. Photos by Shailendra Pandey

|

HAVE YOU ever seen a rough diamond?” asked Navratan

Kothari, his 70-year-old voice, a tragicomic mix of despair and hope. The

diamond he described is an 18th century palace of pleasure — the Jal Mahal. A

jewel that floats in the middle of Jaipur’s Man Sagar,

one of India’s largest manmade lakes. Until Kothari ‘polished’ it, the Jal Mahal and the surrounding

17th century lake had been the dumping ground of the city’s sewage. The palace

with sewage-soaked walls and ravaged floors was in ruins. The Man Sagar lake in which it sat was a

floating cesspool. The migratory birds were long gone. The Mahal’s

only inhabitant — the occasional lost pig.

|

In 2010, after a six-year clean-up, the Man Sagar became a proud home to more than 40 species of

nesting birds. Cormorants flew in and out. Ducks waddled on the now-pleasant

smelling waters. A large turtle lifted its big green head to bask in the

afternoon sun. A group of pink flamingoes returned. And the Jal

Mahal,

restored and resplendent, was a gleaming palace of pleasure once again.

Bubbling under the surface, however, were

countercurrents that stacked up this story differently. As a

story of crimes and misdemeanours. Three

petitioners took Navratan Kothari to court, charging

him with criminal conspiracy. Of cheating and forging

documents to snatch priceless heritage for private profit.

The police probed these allegations against this

perceived heretic three times, each time returning to the Rajasthan High Court

without a smoking gun. But the court wouldn’t take ‘no’ for an answer. It

chided the police for failing to see a larger conspiracy between Kothari and

political actors, and on 16 November 2011, issued a non-bailable

warrant against him. Then, on 17 May this year, Chief Justice Arun Mishra ruled that the work done by Kothari’s company

be reversed. The nalas that had been diverted from

the lake must be restored to their former condition. In other words, the sewage

nalas were directed to be channelled

back to the lake. There was a warrant out for Kothari’s arrest, forcing him to

flee the city; until reprieve came on 25 May. That’s when the Supreme Court

stayed the Rajasthan High Court order, putting the question of Kothari’s

criminal culpability in pause mode till both sides of the case are heard.

Conspirator or not, the story of Navratan Kothari is the kernel around which much larger

questions of development, history, culture and conservation are woven. In the unravelling of the story of the Man Sagar

and the Jal Mahal lies the

answer to a basic question — do we value our heritage? Do we aspire to turn our

cities into concrete-and-glass citadels and ‘Shanghai’ them down a certain

path? Or do we care to listen to the voices of old cities such as Jaipur,

Delhi, Hyderabad or Lucknow and look in their

ramparts for answers to sustainable living.

|

But like all good crime stories, it’s important

to describe the jewel in question. In 1596, Rajasthan was in the grip of a

severe famine. To prevent a recurrence, the ruler of Amer,

Raja Man Singh I, built a dam on what was then the Darbhawati

river to create the Man Sagar lake

in 1610. In 1727, two decades after Mughal emperor Aurangzeb died and the

empire’s grip on princely states such as Rajasthan had loosened, Raja Jai Singh

asserted himself and built the fortified city of Jaipur. In true Rajput

fashion, the warrior king soon felt the need for a pleasure pavilion to get

away from the war and intrigue that was his day job. So, the Jal Mahal was built in 1734 as a

weekend getaway.

After Independence, the lake and palace became

the property of the Rajasthan government and was slowly turned to wasteland. By

1962, the expanding city of Jaipur needed vents to discharge the city’s growing

volumes of sewage. The two stormwater nalas of Nagtalai and Bramhapuri became the dumping ground, carrying the refuse

from the city directly into the lake. The stench from the lake was unbearable

for people living in the vicinity. Rafiq Ahmed, 77,

who lives in Hazrat Ali Colony at the edge of the

lake, describes the discomfort: “When I got my daughter married here 21 years

ago, the guests said ‘Instead of food and drink, we wish you had supplied us

with ittar (perfume).”

THE STRUGGLE to get Jal Mahal

out of the stink began in 1999 when the state government asked private

developers to clean up the Man Sagar lake and restore the Jal Mahal under a public-private partnership — the new buzzword

to get private investors interested in development. The state would do its bit

to clean up the lake by tapping into the Rs 25 crore National

Lake Development Fund. The private firm would do the rest — restore the Mahal and also pay for the annual maintenance of both the

monument and lake. In return, the company would get 100 acres in the vicinity

of the lake, which it could develop into a tourist hub.

|

Many companies, including those with vast experience

in restoring heritage, such as the Neemrana Group,

attended the pre-bid meeting. But as Neemrana founder

Francis Wacziarg pointed out, the road ahead in such

a project could be rocky. So his group, along with other interested parties,

beat a hasty retreat. “It was so complicated and very demanding in cost and we

didn’t have those kind of funds to clean up the lake.

And in our experience, in public-private partnerships, the P of the private

works but the P of the public does not seem to work,” he says.

Eventually, it came down to three companies, and

the KGK Consortium led by Kothari won the bid by

quoting a price 39 percent higher than the nearest rival. It also paid the

minimum bid amount that was 1.5 times more than what the state government had

asked for ( Rs 2.5 crore). The KGK Consortium was an

amalgam of various companies led by Kothari and christened The Jal Mahal Resorts Pvt Ltd.

Kothari’s team soon found out that Wacziarg was right about the public part of the partnership

not quite working. After emptying Rs 25 crore from the lake fund, at the time the property was

handed over to Kothari in 2004, the lake was still stinking. The government

told Kothari that if he wanted to do more, he’d have to spend his own money on

the clean-up job. So, project director Rajeev Lunkad hunted high and low for

someone who knew how to restore a manmade lake. Finally, he zeroed in on German

engineer Harald Kraft, who took one look at the

stinking Man Sagar lake and

said, “It’s an impossible task. You guys are mad to try cleaning this. I love

it, I’ll do it.”

First, Kraft’s team decided to join the two

sewage nalas so that all the dirt converged at once

place, making it easier to clean. This water was treated and then diverted into

a sedimentation tank carved from a small corner of the lake. It was designed

like a deep trough so that the plastic and other refuse would settle at the

bottom to be scooped out later; and the clean water could flow back into the

lake. But this wasn’t enough. The 250-acre lakebed had soaked up so much sewage

since the 1960s that it had to be dredged out entirely and refilled.

In the first rain after the sedimentation tank

was built and the nalas diverted, the results were

dramatic. According to studies conducted by specialists hired by the Jal Mahal Resorts, in the summer

of 2007, the organic waste measured in BOD (biochemical oxygen demand) showed a

sharp drop. It was 450 BOD going into the sedimentation tank, but only 25

coming out. The number of e-coli bacteria in the lake had also shrunk; from 24

lakh in 2000 to just 7,000 in 2009-11. People living in the adjoining colonies

said from 2009 on, they could proudly declare their address to relatives and

guests with heads held high instead of in shame. The stench was gone and so was the unbearable swarms of mosquitoes.

Meanwhile, the team was also busy restoring the Jal Mahal. Historian Giles Tillotson, who has written extensively on the history of

Jaipur, figured out how this would be done. “If you want to give a building

life, it has got to be a new life. You can’t turn back time,”

he said. This meant keeping the spirit of the pleasure palace intact, but

intelligently reusing it. The interiors of the Jal Mahal became a moveable feast of pleasure paintings from

the past two centuries. Blown up to dramatic scale, they are an ode to the rain

gods and to water.

Vibhuti Sachdev curated the

art alongside anthropologist and restoration expert Mitchell Abdul Karim Crites. And so, the arts and crafts of Jaipur,

languishing in forgotten museums in cobwebbed corners, got a new lease of life.

Sachdev explained how craftspersons,

often used only for repair work, now had the opportunity to drive the design of

the project.

Deependra Singh, who was managing the craftspersons,

was misty eyed when he described how it all came together. The scarred floors

and ceiling — ravaged by time and neglect — were marbled and latticed, turning

the gnarled face of the palace into the ravishing beauty it once was. “All your

names and addresses will be put up next to your work,” Singh told the craftspersons. “Well, if foreign tourists, especially

women, are going to see my work, please write my name in English,” said one

artist with excitement.

The biggest challenge was the reconstruction of the

terrace garden, the crown jewel of the pleasure palace. Crites, who was mainly

responsible for this, decided it would be filled with scented white flowers

from around Jaipur — chamelis, champas

and white lotuses. It was named Chameli Bagh. The garden is a happy blend of 18th century India and

contemporary playfulness with some drama added by fountains and cleverly

embedded lighting.

The lighting was a masterstroke of specialist Dhruvjyoti Ghosh, whose firm has

lit up the Humayun’s Tomb in New Delhi and the Sydney

Opera House. The ensemble gives the Jal Mahal a mystical, magical look after sunset. Even before

the garden work was done, it made it to a BBC sponsored book, Around The World In Eighty Gardens by British journalist Monty

Don.

|

With the lake now clean and full of water,

project director Rajeev Lunkad turned to Deependra

Singh one Friday morning with a seemingly impossible deadline. “I need a boat

in this lake by Monday.” Deependra went to Varanasi

in search of boatmen and a day later had managed to track down a suitable man

with a traditional timber boat. There was the small matter of convincing him to

sell his best boat and also accompany it to Jaipur, leaving his flourishing

business in Varanasi behind. That’s when Shah Rukh

Khan came to the rescue. “I told the boatman Aashu, ‘Come with me to Jaipur. The company I work for owns a big

multiplex. We will go see the new Shah Rukh Khan film

Rab Ne Bana Di

Jodi’.” That did it. Aashu found a large

container to cart the boat to Jaipur and by Monday morning the first of four

timber boats set sail in the cool, clean waters of the Man Sagar

lake. Four centuries of damage were undone in six

short years. Jaipur had recovered a piece of itself.

BUT NOT everyone was happy. Precisely when the palace was ready for its

first batch of tourists, a certain set of observers decided it was time to be

upset. Bhagwat Gaur, 30, a high court lawyer, had

been making an inventory of activities around the lake. His biggest objection

was the fact that land along a lake, which is a natural resource, was given

away for private development, for what he felt was a ridiculously low price.

Gaur dug into the tendering process and the conditions of the bid. Kothari’s

actions were now being written up in rough police registers as crimes.

For Gaur, the entire bidding process violated

the principles of public trust because the lake was sandwiched between reserved

forest and no environment impact study had been done before carving out the

project for the bid. He also alleged that the government filled up 13 bighas of the lake with silt to make up for the 100 acres

leased out to Kothari’s company for the lakeside development project. That the

value of the 100 acres in 2010 (when Gaur took the matter to the Rajasthan High

Court) was Rs 3,500 crore,

so leasing it out for an annual fee of Rs 2.5 crore was a paltry sum for the government to collect. It

amounted to “handing over a valuable natural resource to a private entrepreneur

at the cost of the public”.

Furthermore, Gaur argued that carving out the

sedimentation tank from within the lake ruined the lake’s architecture and

ecology. And finally, the original bid said the project would be given to a

public or private limited company but Kothari’s firm was neither. It was a

partnership firm and the rules were bent to suit them, making the bid a

violation of the Constitution and illegal.

Kothari’s lawyers argued against these claims,

backed by the state government — whose various agencies were also named

criminal conspirators. They argued that the Man Sagar

lake does not come under the category of reserved

forest land, that the government agencies had, in fact, got all the necessary

clearances for the project. That it was earmarked for a public-private

partnership right from the 1975 Jaipur city Master Plan onwards. That if the

government indeed acquired 13 bighas of lake to make

up a 100 acres to be given on lease, then equally, the restoration of the lake

has also resulted in its spreading over a larger area than before. So that the lake size has actually increased from 250 acres to more

than 300 acres, as per revenue records.

Kothari’s team also argued against the

perception that the 100 acres was leased out for a song. They said that in 2003

when the bid was won, the land price was Rs 900 crore and not Rs 3,500 crore. In addition, the built-up area they are allowed is

only 6 percent of that. So the price of the land they are allowed to build on

was actually worth not more than Rs 50 crore.

|

Crucially, they questioned the logic of the

petitioner’s case that property around a lake should not be leased out. They

argued that the Jal Mahal

is not a protected monument and had fallen into neglect. Why would a private

party restore it unless there is an incentive, especially since the cleaning up

of the lake and the monument eventually cost Kothari’s consortium Rs 80 crore? Instead of an

outright sale of the land along the lake, the government felt it would be wiser

to ask the private developer to put aside a recurring deposit every year for 99

years. The private party would benefit by not having to pay a fat sum upfront.

And the government would get an annual maintenance fee instead. They also made

the point that the sedimentation tank that ate into 5 percent of the lake was

set up to clean the lake — to restore and improve its ecology, not the other

way around. And that the government had allowed a partnership firm to be part

of the bid because their financials were all in place and that it increased the

competition in the bidding.

The high court remained unconvinced of the

arguments made by Kothari’s team. It ruled that the bid was indeed fraudulent,

unconstitutional and a violation of public trust. However, to get lost merely in

the legalese of the Jal Mahal

case is to miss an important point. Hiding in the subtext of the court papers

is the real reason the restoration of the Man Sagar lake and Jal Mahal

were so supremely stuck: Politics.

THE TELLING of this part of the story is not straightforward at all. But it

all begins with asking one question — who are the petitioners and why did

people like Bhagwat Gaur decide one fine day to make

the restoration of the Jal Mahal

a cause to fight for? Especially since he admitted to TEHELKA that he had not actually set foot on the lake or

inside the Jal Mahal after

it had been restored. The last time he had been in there was as a

student, many years ago. It was only in 2010, after four years of work on the

lake and palace were over that Gaur, having watched big earth-moving machines

in operation from afar, decided that this disturbed him. A story in the Rajasthan

Patrika headlined, ‘Will the lake be without

water?’ added to his alarm. “The government should not give monuments to the

private sector for protection. Not just the Jal Mahal. Even the Neemrana Fort in Alwar was given to a private company. I’m against that,” he

said.

Gaur founded a society called Dharohar Bachao Samiti (DBS) and got it registered in March 2010. Two

months later, he filed a public interest litigation (PIL) against the Jal Mahal Resorts Pvt Ltd in the

Rajasthan High Court. It seemed curious to TEHELKA

that Gaur’s interest in heritage was sparked only two months before he filed

the PIL. However, Gaur explains that the society had

been meeting informally for a few months before that. But when the Jal Mahal project became his big

cause, he realised that the DBS needed to be formally

registered.

|

Where did Gaur’s vehement disapproval stem from?

Had he spoken to conservationists or lake experts? “Some things cannot be

disclosed,” was his mysterious reply. Then, there was another curious event.

Soon after the PILwas filed, Gaur and DBS president

Ved Prakash Sharma had a public

fallout. Gaur called him unscrupulous and a double-dealer and asked him to

leave the society. At which point, Sharma filed an independent case against the

restoration after registering himself as a separate society — the Heritage

Conservation Society. Sharma’s lawyer Aruneshwar

Gupta vouches for his client’s integrity and commitment to the cause of

heritage. “He’s a historian. Not a published historian but a social historian.

Let me put it this way, he is a social activist. One of his PhDs is on the

heritage of Jaipur.”

One year after Gaur and Sharma formed

conservation societies and took the Jal Mahal project to court, a third petitioner joined their campaign.

Professor KP Sharma, head of the Botany Department at

Rajasthan University, told the high court that after the restoration, the

lake’s salinity had increased to alarming levels. His report has became part of all three court

petitions.

The fact that salinity levels of lakes in urban

areas constantly increase over time is a universal truth among botanists. The

Man Sagar lake is in the

middle of a dense metropolis where the groundwater is highly polluted. For KP Sharma to extrapolate from the increasing salinity

levels that it will lead to the entire lake drying up is not based on

scientifically verifiable data, say other botanists. A study published in the Journal

of Hydrological Research and Development pours cold water on Sharma’s

theory. Using primary data collected by the Jal Mahal Resorts and some data of their own, scientists AB

Gupta and three others concluded that the “lake restoration measures like the

diversion of sewage from the treatment plant and provision of the settling tank

have resulted in a significant improvement of lake water quality”.

But the real clue to the politics at work behind

the stalled Jal Mahal

restoration comes not just from the intent or background of the petitioners,

but a point they made in their petition. They had told the court that Navratan Kothari’s biggest crime was that he was favoured by the Ashok Gehlot-led

Congress government, since the lease was signed just a day before its term

ended in December 2003. And for the most of the Vasundhara

Raje Scindia-led BJP regime

that followed, the fresh development plans for the 100-acre lakefront plot were

never signed.

In fact, one of the partners in Kothari’s

consortium is the firm Kalpatru, believed to be close

to Gehlot. It is widely alleged that it is this

connection that got Kothari the project in the first place. As a result, a

project setting out to give back Jaipur a piece of itself was caught in a

political slugfest between the Congress and the BJP.

The timing of the lawsuits against Kothari’s

firm makes for even more interesting observation. Even though the lease was

signed on the last working day of the Congress regime, the project was reviewed

at great length by the BJP-led Raje government. On 27

October 2004, the BJP government signed the lease and licence

deeds. The permission to converge the two nalas and de-silt the lake was given by the environment

ministry and the state Urban Development Secretary. It was only after the

restoration work was complete and the time had come for Kothari to rake in some

profit by developing the 100 acres by the lakeside that he was taken to court.

While the restoration work continued even under

the BJP government’s tenure, the new layout plans for the hotel, restaurant and

crafts bazaar that were to be built on the lakefront, got stuck in approvals.

These plans eventually got passed in 2009, when the Congress returned to power.

This became the subject of a heated political debate in the state Assembly.

In February 2011, Rajasthan Tourism Minister Bina Kak raised questions about

the intent of the Raje government in holding up the Jal Mahal development plans from

2006 to ’08. She accused the BJP of deliberately holding up the plans because

an illegal demand for a partnership in the project didn’t come through. This

was Kak’s oblique way of hinting that the Raje government had its eye on the Jal

Mahal project and that was why the project’s plans

were held up. The BJP MLAs denied these allegations

and stormed out of the Vidhan Sabha.

The questions triggered by the debate hovered

over the Jal Mahal project

like dark clouds. They also led TEHELKA to ask if

there were any links between the petitioners and Raje.

The legal counsel for two of the petitioners denied ever having met the former

CM on the Jal Mahal issue.

But a curious happenstance TEHELKA stumbled upon

makes these denials seem less convincing. When TEHELKA

contacted Raje to ask her about the Jal Mahal project, she said, “I

will get my office to send you documents on the case. Read those and then we

can talk.” Her press secretary emailed TEHELKA the

court documents and also a list of points titled ‘Jalmahal

synopsis’. It’s an email that her office did not realise would connect Raje

directly to the Jal Mahal

petitioner — Bhagwat Gaur. The email was actually a

forward from Raje’s email account, where the original

sender was Gaur’s lawyer Ajay Jain. When TEHELKA

confronted Raje’s office on this connection between

her and the petitioner, we were informed that it was for our benefit that Raje’s office had contacted the petitioner. “You can write

what you like but there is no connection between the petitioners and Raje,” her press secretary said with consternation.

A STORY that started out as an attempt to protect and restore the Man Sagar and Jal Mahal

had now become the theatre for ugly political shadowboxing. Alongside Kothari,

three other government officials, who signed on various documents approving the

Jal Mahal restoration, were

also named as criminals and co-conspirators. But if the government and Kothari

are the villains of the piece, then many others in the conservation business

argue, it’s a forbidding omen for future public-private partnerships.

Indeed, the Jal Mahal restoration story is the pivot around which much

larger questions turn. It could either be held up as a role model for how much

of our heritage can be saved or an ominous sign that heritage is the new

theatre for property wars; its new protectors, the real heretics. Which leads

us to the overwhelming question — How should we

protect and preserve our history, culture and identity?

Conservation architect Anisha

Shekhar Mukherji says

Kothari’s predicament is faced by many, including herself. While working on

Delhi’s Jantar Mantar, she

said: “The entire process of what we were doing had to be re-explained each time

the head of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI)

changed.”

The Aga Khan Trust project director Ratish Nanda puts this in sharp relief. “We still look at

heritage as a burden rather than an asset, which it actually is,” he says. “If

Agra was in Europe, the quality of the citizens’ lives would be very high. We

need to move from a punishment-based system to an incentive-based system,

including the change of land use and tax exemptions. Right now, there are no

incentives but a lot of penalties.”

Conservationist Gurmeet

Rai zeroed in on a crucial missing piece. India has

no legal framework for public-private partnerships. Rai,

who is the director of Cultural Resource Conservation Initiative, explains how

world over, partnerships are the byproduct of an overview a country has of its

heritage. However, in India, no roadmap exists. Therefore, the projects that Rai has been part of have also got stuck in court.

One such was the Nabha

Fort in Punjab. Like the Jal Mahal

project, this was also a public-private partnership. The project was the

initiative of the grandson of the Maharaja of Nabha.

But a petitioner feared that the private player will turn the fort into a mall

and filed a public interest litigation. The Punjab

High Court eventually gave what Rai calls a “historic

verdict”. It said that encouraging the private sector to invest in cultural

heritage is a good thing.

We are now in the 150th year of the

Archaeological Survey of India. While conservationists such as Rai, Mukherji and Nanda all work

with and respect the expertise of the government body, there is a universal

agreement on the need for change. In the way heritage is viewed, and contracts

are drawn up. Everyone agrees that given the vast number of forgotten palaces

and vandalised forts we have, and the countless forms

of lived heritage in our midst, preservation cannot just be the job of the

government. The private sector will need to step in.

But if public-private partnerships are the way

forward, the road ahead will have to be paved with more than just good

intentions. The Jal Mahals

and Man Sagar lakes need to exist in an environment

that understands why we need our past. And how it is an

important part of our present. We need cities to be spaces where malls

and monuments are not necessarily opposites. But can speak to each other

through shared spaces.

The apex court will now decide whether Kothari’s

revival of the Jal Mahal

was right or wrong. Whether the 80 crore he has

already spent in restoring the lake, the lakefront and the Jal

Mahal brings something back to the city. Or if people

like Gaur are right in asking for the sewage nalas to

be put back into the lake. But Kothari’s real crime is now firmly established.

As someone whose vision for Jaipur is caught in a forgotten circus of

administrative and legal holes. Where contracts are part of

political jugglery. Kothari is a private player on a public trampoline.

For this, he is now being punished.

Revati Laul is a Special

Correspondent with Tehelka.

revati@tehelka.com

Return to Dead Parrot homepage.