Cubism: The Leonard A. Lauder Collection

20 October

2014 – 16 February 2015

Metropolitan

Museum of Art

Cubism: The Leonard A. Lauder Collection presents

for the first time the entire collection of works that Mr. Lauder

pledged to the Metropolitan Museum in April 2013--a billion dollar unrestricted

gift that ranks as one of the most significant in the history of the Met. With 81

paintings, works on paper, and sculptures (34 by Picasso, 17 by Braque, 15 by

Gris, and 15 by Léger), The

Leonard A. Lauder Collection is

one of the most significant collections of Cubist works in the world, and certainly

the most significant ever to have been held in private hands. The Met's

collection now has become at least on a par with that of MoMA

and the Pompidou Center in Paris--making New York now the place to

go to see the pivotal examples of the best work of that period.

This is an amazing collection, and a

fabulous show. We plan to return numerous times. You

should not miss it!

Emily Braun (who served as curator of Mr. Lauder's collection)

and Rebecca Rabinow (the recently

appointed Leonard A. Lauder Curator of Modern Art at the Met) co-curated

this magnificent exhibition and also edited the catalogue for the

show, which includes 22 essays by 17 preeminent scholars--ranging

from important art historians and museum curators to unexpected contibutors like Nobel Prize-winning

neuroscientist Eric Kandel--which uses the works in the collection along

with other works to create a far reaching discussion of the theory and

history of Cubism. This wonderful catalogue begins with a conversation

between Leonard Lauder and Emily Braun, entitled "A

Collector's Story," in which Mr. Lauder discusses the origins

of how he first came to be a collector, how in 1976 he began the 35 year effort

of collecting Cubist works, and what that process was like. He says that

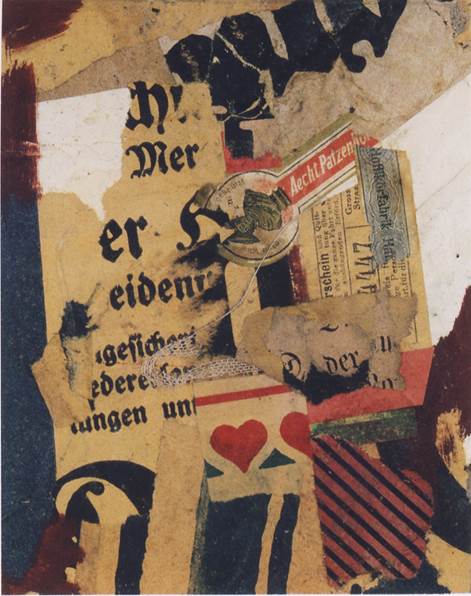

his first "serious" acquisition was a collage by Kurt Schwitters, Mz

79. Herz-Klee. Although

this work is not Cubist and is not in this collection, it does appear

in the catalogue as part of this conversation; and I reproduce it here because

it is so wonderful--and such an amazing first major acquisition:

Kurt

Schwitters.

Mz 79. Herz-Klee. 1920. Printed papers,

India ink, fabric netting, and thread on paper.

Braque and Picasso are the real stars of The

Leonard A. Lauder Collection--and, of course, they were

the real stars of Cubism, which they founded. More than half of

the Collection focuses on the period from 1909 to 1914 when Braque

and Picasso collaborated closely.

In 1907, Braque had still

been working in a Fauvist style. As Jack Flam points out in

his essay in the catalogue, "The Birth of Cubism: Braque's Early

Landscapes and the 1908 Gallerie Kahnweiler

Exhibition,"

In

September 1908 Georges Braque submitted to the jury of the Salon d'Automne six Cezanne-inspired pictures... The jury, headed

by Henri Matisse, rejected them; Matisse reportedly described the refused

canvases as being full of "little cubes." Stung by the

rejection, Braques arranged instead to show

thirty-seven of his recent works at Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler's

gallery... That exhibition, which ran from November 9 to 28

marked the birth of "Cubism" as a concept.

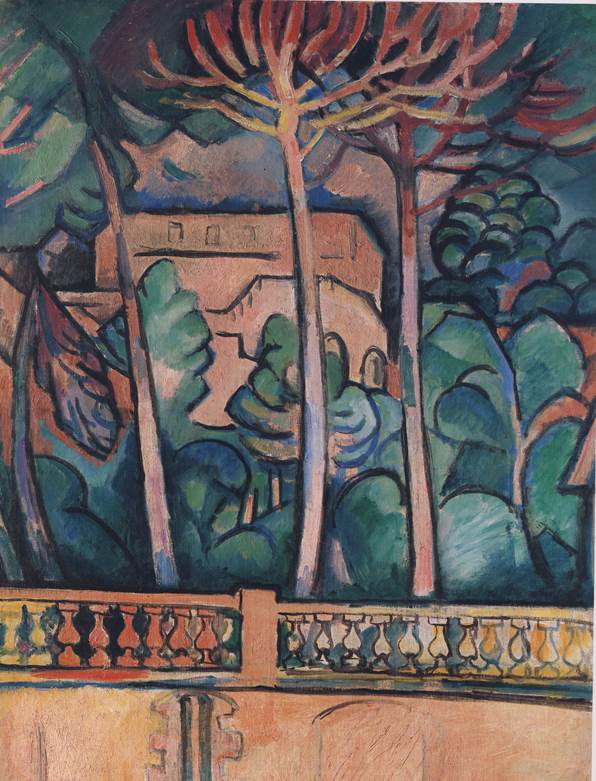

The Collection includes two of Braque's

landscapes from this historic show: his 1907 The Terrace at the Hôtel Mistral, which marks Braque’s

transition from Fauvism to Cubism,

Georges

Braque. The

Terrace at the Hôtel Mistral.

Autumn 1907. Oil on canvas.

and, a year later, the all-important Trees at L’Estaque, which has been said to have inaugurated

Cubism:

![braquelauder[1]](Lauder_files/image006.jpg)

Georges

Braque. Trees

at L'Estaque. Summer 1908. Oil on canvas.

Flam notes that by the time Braque painted Trees at

L'Estaque,

he had not

only seen the two big Cézanne shows but also Picasso's Les demoiselles d'Avignon, which produced such a state of shock that he

later said that he felt as if he had been forced to eat tow or drink

kerosene. By then Braque was assimilating into his own painting the

geometrical substructures, spatial fracturing, and dynamism that he so admired

in Cézanne, while giving himself the freedom to work with some of the roughness

and uninhibited angularity he had seen in Picasso's large canvas.

And, of course, Les demoiselles d'Avignon was a seminally

important moment in the process leading up to what was to become Cubism--not

least because it demonstrated the effects of African art on the development of

Cubism--and the art of the twentieth century in general. In fact, it used

to be in vogue to claim that it was the first Cubist painting,

although it currently is viewed more correctly as the first

"proto-Cubist" work. (If one wants to think competitively

about the importance of the Met and of MoMA in this area, MoMA having the

iconic Les demoiselles d'Avignon gives

it no small leg up.) The

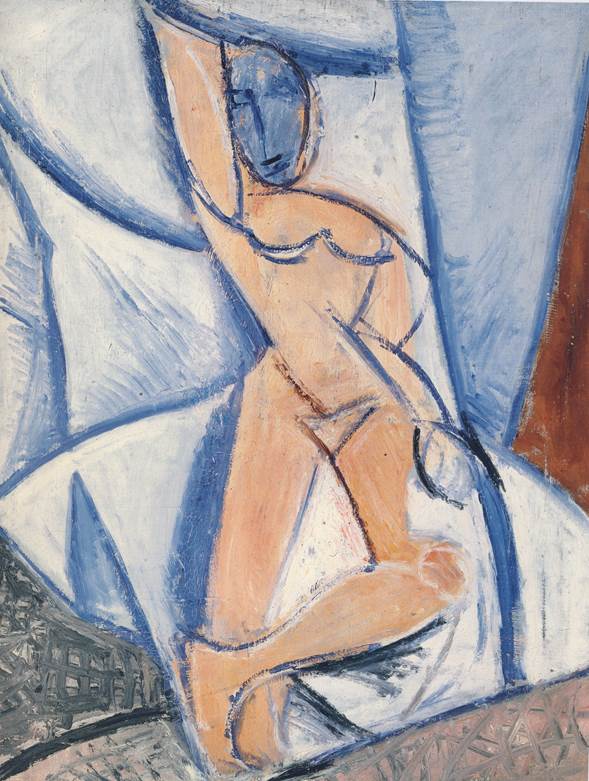

Leonard A. Lauder Collection has

an extremely beautiful and wonderful painting Picasso did as a study for Les

demoiselles d'Avignon, Nude

with Raised Arm and Drapery:

Pablo

Picasso. Nude

with Raised Arm and Drapery. Spring-summer

1907. Oil on canvas.

Michael FitzGerald in his essay, "Picasso, Cézanne, and Accounts

of Early Cubism," discusses the complex relationship Picasso

had to the work of Cézanne--whom he on the one hand said he "was like our

father," and on the other seemed to feel he was more like a rival

"peer than a predecessor." He also discusses the complex

question of whether it was Picasso or Braque who was more

directly responsible for the creation of Cubism. Many of his works, like

the wonderful The Chocolate Pot from 1909, show the

intensity of Picasso's relationship to Cézanne:

Pablo

Picasso. The

Chocolate Pot. Early 1909. Watercolor and gouache with traces of charcoal on white laid paper.

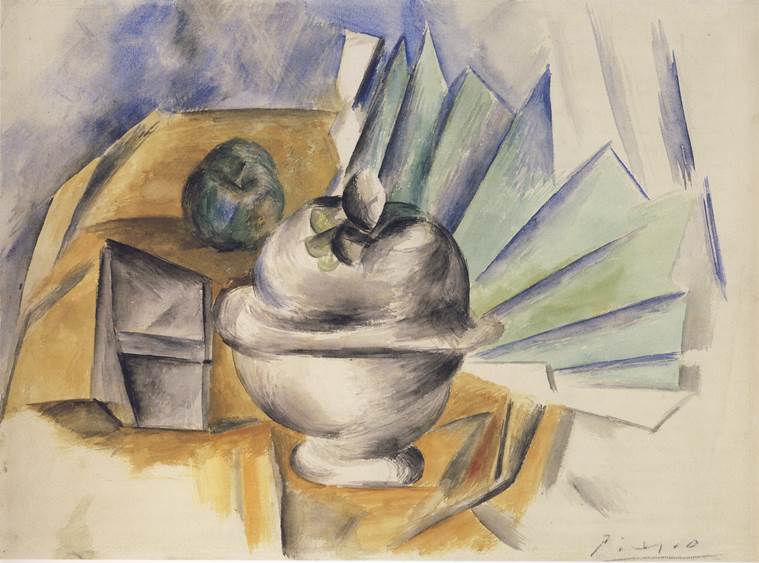

as does his slightly later and equally wonderful Sugar

Bowl and Fan:

Pablo

Picasso. Sugar

Bowl and Fan. Autumn1909. Watercolor on white

laid paper.

While I personally almost always

prefer the works of Braque to those of Picasso, they are both geniuses

of monumental importance in the history of art; and they were both clearly

pivotally involved in the development of Cubism. The work of Cézanne

obviously had a profound influence on both of them (it had an enormous impact

on all of the originators of twentieth century art; Matisse, while

a nay-sayer early-on about Cubism, referred to Cézanne as "the father

of us all") and was a formative influence in the development of

Cubism. Nevertheless, I believe it was through Braque that

the most profound Cézanne influence affected Cubism. (On the other

hand, it was clearly via Picasso that African art influenced

the growth of Cubism.) The simple truth is that Cubism was the creation

of both Braque and Picasso; and, in fact, the direct

interaction between them was essential in the process. And, as the Met's

online write-up points out,

By 1909

Braque and Picasso were inseparable. As Picasso later recounted, “Almost every

evening, either I went to Braque’s studio or he came to mine. Each of us HAD to

see what the other had done during the day. We criticized each other’s work. A

canvas wasn’t finished until both of us felt it was.”

In fact, they worked together

extensively, sharing a fertile back and forth in their creative growth.

Braque’s Fruit

Dish and Glass (1912), the very first Cubist papier

collé (paper collage) ever created, is also in

the Collection. Collages were a revolutionary Cubist art form in which

ready-made objects were incorporated into fine art. In the summer of 1912,

while vacationing with Picasso in the south of France, Braque saw imitation

wood-grain wallpaper in a store window. He waited until Picasso left town

before buying the faux bois paper and pasting it into a still-life composition.

Braque’s decision to use mechanically printed, illusionistic wallpaper to

represent the texture and color of a wooden table marked a turning point in

Cubism. Braque later recounted, “After having made the papier

collé [Fruit Dish and Glass], I felt a great

shock, and it was an even greater shock for Picasso when I showed it to him.”

Georges

Braques.

Fruit Dish and Glass. autumn 1912. Charcoal and

cut-and-pasted printed wallpaper with gouache on white laid paper.

It is impossible to overstate

the importance of the invention of collage in the development of

Cubism--or of abstract art in general. Collage speaks directly to the

main themes in the movement toward abstraction, from the Impressionists and

Post-Impressionists, through the Cubists, and beyond: it emphasizes the

physical surface of a painting, even while creating pictorial depth in the

composition; it plays back and forth between physical reality and

representational reality in a way that is an unavoidable, self-referential

comment on the process of artistic creation itself; and, in the end, it

tends to emphasize the formal, compositional and structural elements of a

work, rather than the representational. Picasso himself

soon took up the papier collé, primarily using newspapers in place of Braque's

wallpaper. A particularly beautiful one from 1912 is included below:

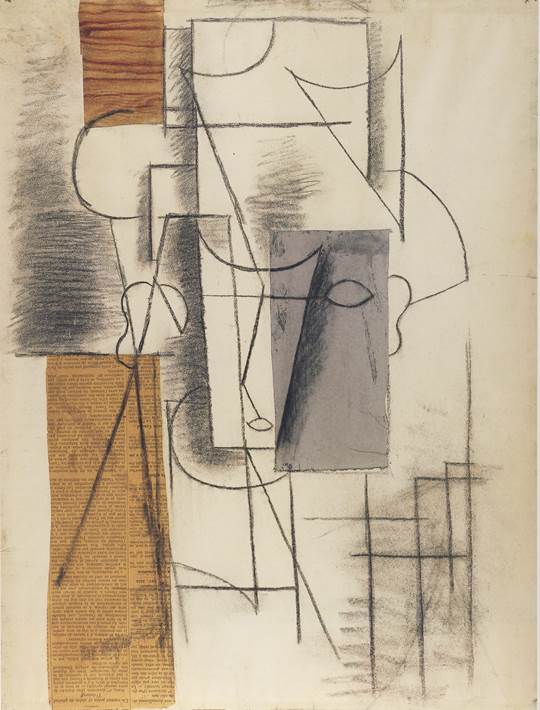

Pablo

Picasso. Head

of a Man. 1912. Charcoal, watercolor, cut-and-pasted newspaper, and gray laid paper on white laid paper.

You will have noted that I have been

focusing only on Braque and Picasso--but that is because I love

the works of these two giants. The Collection also contains great works

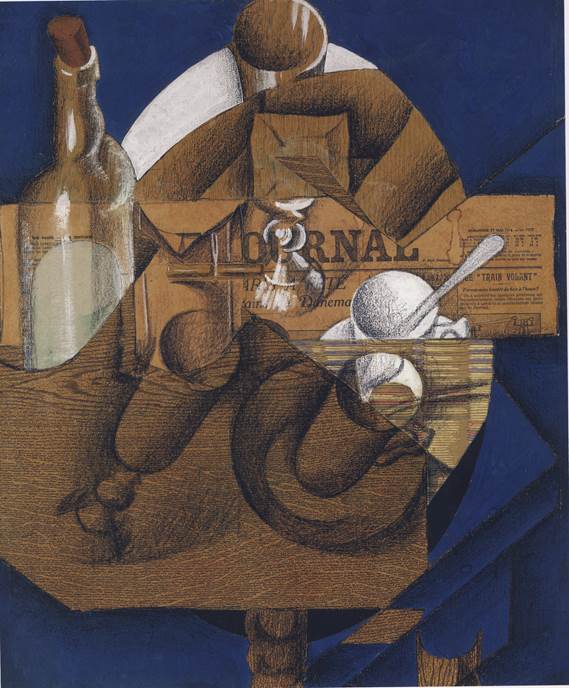

by Juan Gris, like

Juan

Gris. Cup, Glasses, and Bottle (Le

Journal). 1914. Conté crayon, gouache, oil,

cut-and-pasted newspaper, white laid paper, printed wallpaper (three types),

selectively varnished, adhered overall onto a sheet of newspaper, mounted to

primed canvas.

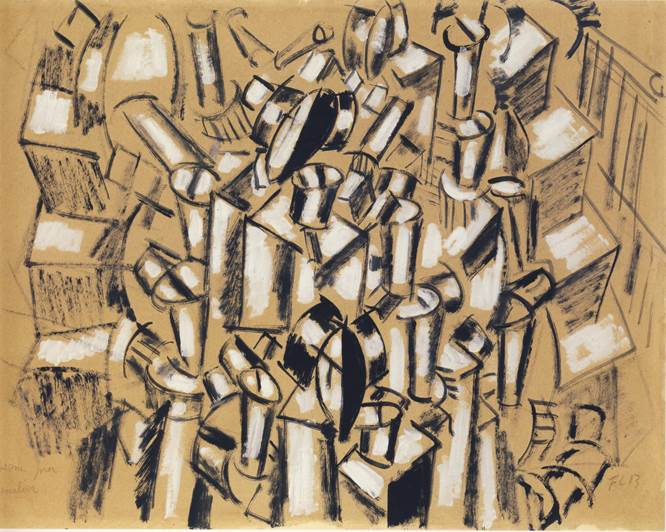

and by Fernand Léger, like

Fernand

Léger. Drawing for "The Staircase." 1913. Gouache and oil on tan wove paper.

or his House Under the Trees:

Fernand

Léger. House Under the Trees. 1913. Oil on canvas.

There is a limit to how many of these marvelous images I can send you. And the ones I am including do not even begin to capture the scope of the treasures contained in this exhibition. The only answer is to get yourself to the met sometime in the next four months and to see the show in person. If you really cannot make it to New York, order the catalogue--it is terrific, and the images are very high quality. (It is available online from Amazon.com)

![]()

Return to Dead Parrot homepage.