Nancy

and I have just spent a marvelous afternoon at the Metropolitan Museum seeing MATISSE:

IN SEARCH OF TRUE PAINTING. This

incredible exhibition (organized by The Met, in collaboration with the Statens Museum for Kunst,

Copenhagen, and the Centre Pompidou, Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris), which

opened in early December, is on display until

17 March 2013, and it simply should not be missed!

Matisse

(1869–1954) was one of the greatest French artists of the first half of the 20th

century, and when he was good, he was extraordinarily

good. Some of his work is among our very

favorite art of all time.

This

show, MATISSE:

IN SEARCH OF TRUE PAINTING, has assembled some fabulous examples of his

painting—some that we haven’t seen since the amazing 1992 retrospective of his

work at MoMA, and some we have never seen. (While many of

these great works are from museums we frequently visit [the Met, MoMA, and the Pompidou Center in Paris], many are from

places we seldom get to [Baltimore, St. Louis, Washington, DC, Philadelphia], some

from places we never get to [Denmark, Switzterland,

Finland, Belgium, and Houston], and some are from private collections. This

fact alone would make the show a necessary experience. But, in addition, this show has attempted to

bring together some of the works Matisse did in pairs or trios or series, which

provides a most unusual insight into the process of his creativity. As described by Rebecca Rabinow

for the Metropolitan Museum's presentation of the show,

Throughout his career, he questioned,

repainted, and reevaluated his work. He used his completed canvases as tools,

repeating compositions in order to compare effects, gauge his progress, and, as

he put it, "push further and deeper into true painting." While this

manner of working with pairs, trios, and series is certainly not unique to

Matisse, his need to progress methodically from one painting to the next is

striking. Matisse: In Search of True Painting presents this particular

aspect of Matisse's painting process by showcasing forty-nine vibrantly colored

canvases. For Matisse, the process of creation was not simply a means to an end

but a dimension of his art that was as important as the finished canvas. (from the Met’s website)

The

comments I quote below from the Met’s online presentation of the exhibition

were written by Rebecca Rabinow, who, along with Dorthe Aagesen, are

the editors of—and important contributors to—the very well-done and informative

catalogue from the exhibition, Matisse: In Search of True Painting,

ed., D. Aagesen and R. Rabinow,

Yale University Press, 2012. (FYI: this

book is readily available from Amazon.com

at $31.50—far below the Met’s $50 price tag.)

My remarks below are highly personal and impressionistic (as, of course,

is the selection of images I have included in my online version of this review);

for a fuller presentation of images and a more extensive, room-by-room

scholarly commentary, I very much suggest you check out the

Met’s online description of the show.

I do include some of what I considered the Met’s most insightful

comments along with my own, below.

Room One

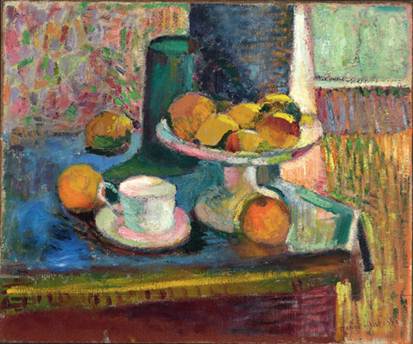

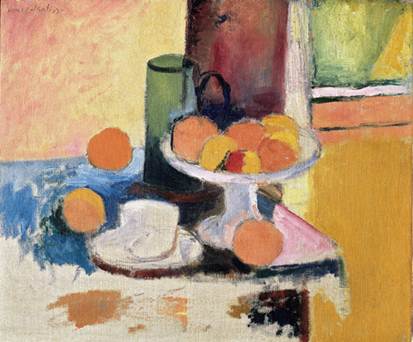

The

online description notes,

Matisse turned thirty in 1899, the year

he painted Still Life with Compote and Fruit (1899) and Still Life with

Compote, Apples and Oranges (1899). He had not yet received any critical

recognition and worried that he would be unable to support his growing family.

For an artist on a limited budget, still lifes were

an obvious and inexpensive subject. Rather than rework a single picture until

it reached a definitive state, Matisse painted these two interpretations on

identically sized canvases. It is not known which was begun first. Both are

related to a larger composition of that year, Sideboard and Table (Kunsthaus Zürich).

Here

are images of the two still lifes Rabinow

is describing. They are both quite lovely, and interesting juxtaposed with one another. (I rather liked the former more than the

latter.)

Still Life with Compote and Fruit, 1899

Oil on canvas; 18 1/8 x 21 7/8 in. (46 x 55.6 cm)

Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, Washington University in St. Louis

|

|

|

Still Life with Compote, Apples, and Oranges, 1899 |

Room Two

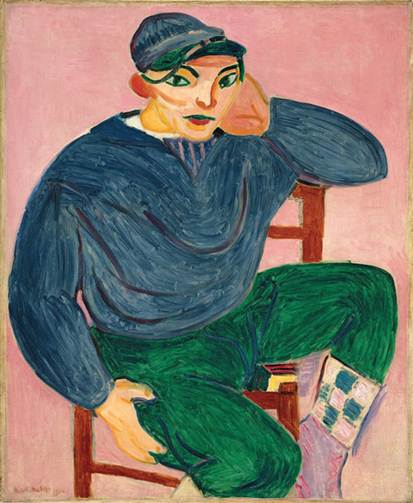

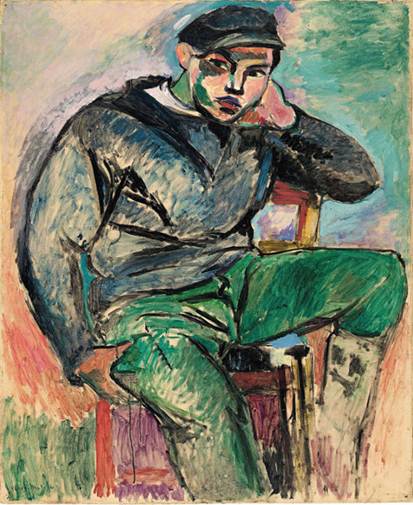

In

1906, Matisse painted two versions of the Young

Sailor. I rather like the earlier

version better. With is Picasso-esque, powerful, proto-Cubist

feel.

Young Sailor I, 1906

Oil on canvas; 39 1/4 x 32 in. (99.7 x 81.3 cm)

Collection of Sheldon H. Solow

In

the reworking, Matisse has simplified the elements—especially the background,

which he has reduced to a monochromatic pink (which Rabinow

claims “evokes Van Gogh's L'Arlésienne, which Matisse had tried in vain to purchase

several years earlier).

|

|

|

Young Sailor II, 1906 |

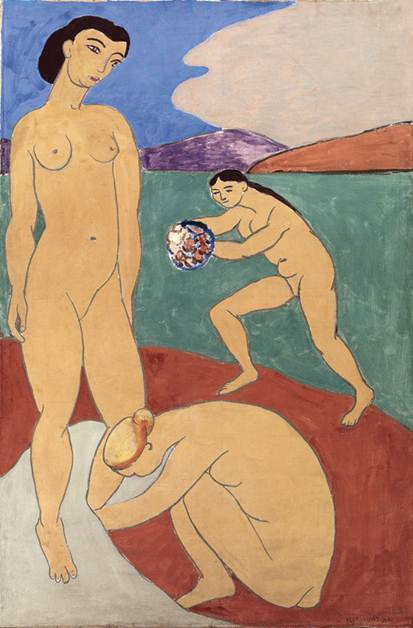

In

the 1907-8 Le Luxe

II, creates a much more interesting, forward-looking, and—to me—pleasing—version

of the earlier 1907 painting, Le Luxe I (also in the show, along with a charcoal on

paper he did of this composition).

Although based on an academic theme, Matisse’s originality and freedom

shines through in this painting.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Le Luxe II, 1907–8 |

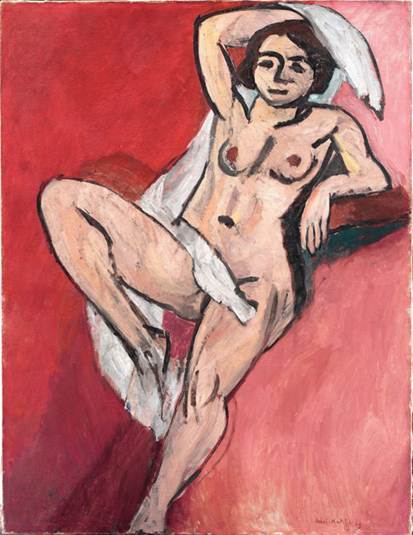

In his pair of nudes from 1909. Nude with a White Scarf (below) is to me

a very good work, while I liked his earlier Seated

Nude far less—as did he, I believe.

|

|

|

Nude with a White Scarf, 1909 |

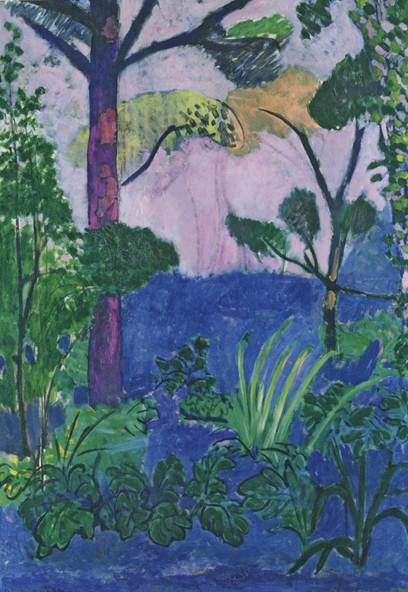

Nancy

and I were totally caught by surprise—and blow away—by his 1912 Acanthus (Moroccan Landscape) (below), with

the incredibly vibrant and resonant range of the purples and violets,

contrasting with greens.

Acanthus (Moroccan Landscape), 1912

Oil on canvas, 45 ¼ x 31 ½ in,

(115 x 80 cm)

Moderna Museet,

Stockholm

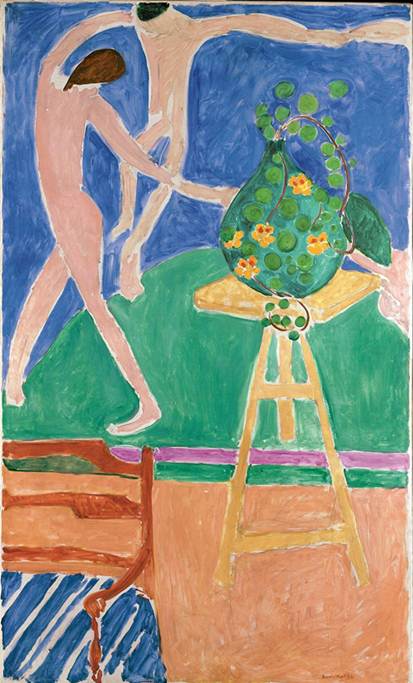

Matisse

painted several views of the interior of his studio (in Issy-les-Moulineaux, just southwest of Paris interior), including Nasturtiums

with the Painting "Dance" I (below). In the background he has painted a representation

his large 1909 painting Dance (now

part of the permanent collection at MoMA), which at

the time was propped against his studio wall; in the foreground there are

objects from his studio—a chair and a tripod table with a vase of nasturtiums

on top of it. The second version (not

included here), is much more heavily worked over and dense in comparison to the

thinness of the pigment of the first; but ultimately it is far less satisfying.

|

|

|

Nasturtiums with the Painting

"Dance" I, 1912 |

Room Three

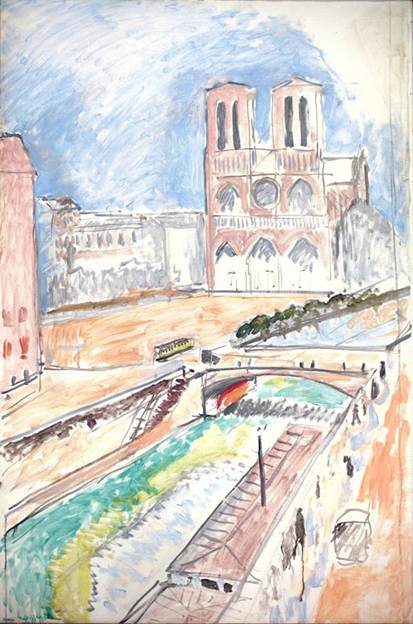

This

room contained four paintings Matisse did of the cathedral of Notre-Dame—all interesting,

but the two large ones from 1914 quite wonderful. They all are views from his studio and contain

elements of his studio within them—some obvious, others, as in the one from MoMA (below), as subtle as a vertical line suggesting the

frame of his window, and curved line suggesting the railing of his balcony. As the online description notes,

Matisse's pictures of Notre-Dame are not

a series per se, at least not in the way that Claude Monet methodically

depicted some thirty views of the façade of Rouen Cathedral during his two

visits to that city in 1892–93. For Matisse the view was part of his daily

life. "I never tire of it," he said. "For me it is always

new." The two larger paintings of 1914 underscore issues that engaged

Matisse in that year: means of representation, the role of color, and the

question of what constitutes a finished canvas.

We

both thought that the one from MoMA (first, below)

was quite fabulous in the evocativeness of its minimalism, the subtle

complexity of its textures, and the elegant beauty of its colors—in particular

his marvelous handling of the shades and saturations of the blues.

|

|

|

Notre-Dame, 1914 While

not as sublime as the painting above, the Notre-Dame,

also from 1914, below is also wonderfully pleasing. |

|

|

|

Notre-Dame,

1914 |

|

1914

is also the year in which Matisse painted some interiors which rank among our

very most favorite pieces in his oeuvre. |

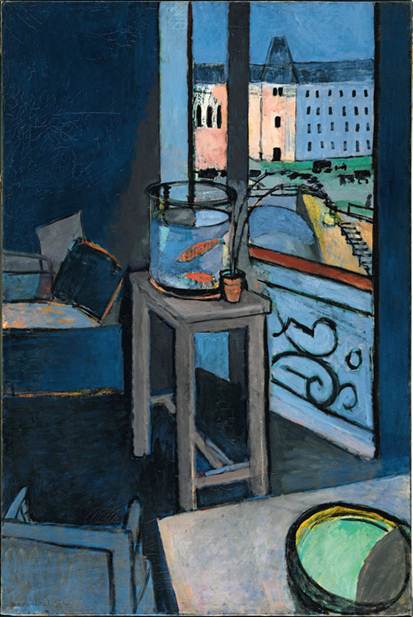

|

One, his sublime Interior with Goldfish (below), is one we spend a great deal of

time looking at in the Beaubourg in Paris—and paused

twice to spend time with in this show.

The deep, rich blues of the interior are highlighted with contrasting

orange elements (the diagonal of the window ledge, the flower pot, and the

goldfish themselves, the outline of the pillow and piece of furniture on

which it is placed, and the mix of colors on the top surface of that piece of

furniture), which actually function powerfully in creating the compositional structure

of the painting. And the details

within the work are endlessly fascinating and satisfying: the curved line of

the fish bowl which mirrors the curve of the underside of the bridge; the way

that the stems of the plant carry one’s eye around to the line of the stairs

on the quay). It is an amazing work of

art. |

|

|

|

Interior with Goldfish, 1914 Goldfish and Palette, also from 1914

(and an old friend from MoMA) is far more abstract and

les directly representational than the one above, and exists far more on the

surface plane of the painting itself. There is a Cézanne-like tilt to table on

which the fishbowl is standing; and there is an almost Picasso-like sense of

geometry. It is another painting of

his we cherish and spend a great deal of time taking in. |

|

|

|

Goldfish

and Palette, 1914 |

In

1916-7 he painted Sculpture and Vase of

Ivy (below), which is the far more interesting of the two by this name (the

earlier one, done in 1916, is not shown here).

In the later version, the deep blues add

meaningfully to the richness of the painting—and effect that is enhanced by

introducing the contrasting vertical tan element of the left side of the

composition. The tilted-forward top to

the dresser adds a Cézanne-like quality and tension to the composition—and there

is something reminiscent of Cézanne in the appearance of the fruit on that surface.

|

|

|

Sculpture and Vase of Ivy, 1916–17 |

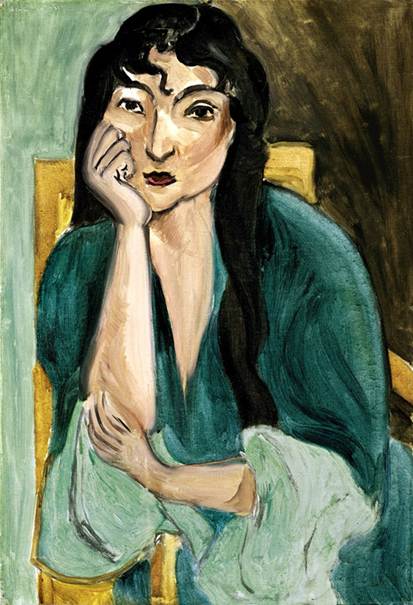

There

is only one of the three paintings of Laurette I

found at all interesting, and it was Meditation (Portrait of Laurette), below. Concerning the woman herself, the online

notes tell us that,

Laurette was the first

professional model with whom Matisse worked over a prolonged period. She posed

for him for six or seven months in 1916–17, a period of intense creativity that

resulted in some fifty pictures of her. Her presence was instrumental in

reorienting Matisse as he abandoned the restrictions inherent in painting in

pairs and fully embraced larger series.

As

with many of the good paintings of Matisse, this one seems to have elements

that are reminiscent of Cézanne—in this case some good allusions to his

portraits of Mme. Cézanne.

|

|

|

Meditation (Portrait of Laurette), 1916–17 |

Room Four

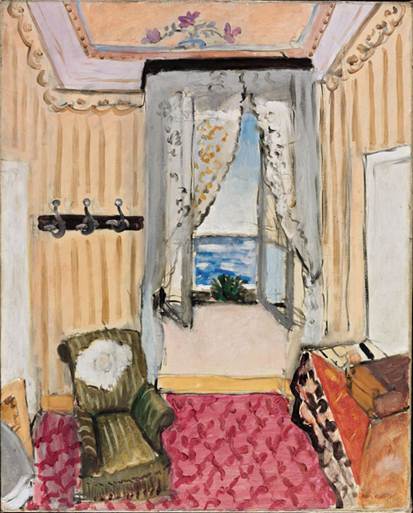

The Open Window

(Room at the Hôtel Beau-Rivage) of 1917-8 (not

included here), is by far the least interesting of the three included in this

show. His 1918 Interior at Nice (Room at the Hôtel

Beau-Rivage) (below), an

almost identical view of the very same elements from the identical perspective,

is wonderfully different in the details of its presentation—and thus a much better painting, with much more

life in it.

|

|

|

Interior at Nice (Room at the Hôtel Beau-Rivage), 1918 |

The

third of this group, Interior with a Violin

(Room at the Hôtel Beau-Rivage), also from

1918, is almost totally different from the other two, even though it is

essentially the same scene in the same hotel room. It is an exciting painting, with an intensity

created by the contrast between the blacks and grays of the interior and the blues

and greens in the bright light outside the window—with the counterpoint, of

course of the intensely bright blue of the interior of the violin case, and the

highlights of yellow and orange inside the room.. According to the online notes:

Matisse repeatedly returned to Interior with a Violin, painting over

his earlier composition. The predominant use of black and gray felt fresh to

him and enhanced his impression of "the silver clarity of the light in

Nice." Matisse considered it to be a particularly important work and later

commented that in this canvas he had used black to paint light.

I

had never heard his use of the phrase, “used black to paint light”—but I love

it!

|

|

|

Interior with a Violin (Room at the Hôtel Beau-Rivage), 1918 |

Room Five

This

room features three paintings which are 1920 variations he painted of a spot on

the beach under the cliffs at Étretat. Neither of us found them to be very good or

interesting. I’d suggest sticking with

the far better paintings done of this area by Gustave

Courbet and Claude Monet.

The

three still lifes included from this period are

slightly better, but nothing to get excited about.

Room Six

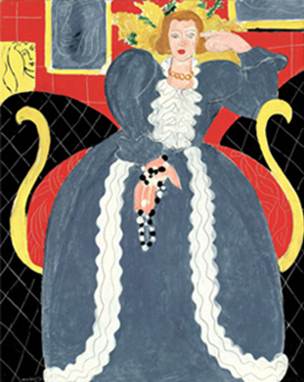

The Large Blue

Dress

of 1937 (below) is not a particularly satisfying painting—particularly in its

subject matter, which we both found more off-putting than engaging. The details of line, color, and composition,

however, are quite interesting and merit close examination.

The Large Blue Dress, 1937

Oil on canvas; 36 1/2 x 29 in. (92.7 x 73.7 cm)

Philadelphia Museum of Art

Room Seven

Room

Seven contains a totally fascinating presentation of works from 1945. In December 1945, there was an exhibition of six

of Matisse’s paintings at the Galerie Maeght, in which each painting was accompanied by a series

of black and white photographs recording stages of that painting’s evolution. In this room, sets of three of the paintings

and accompanying photographs from that Galerie Maeght exhibition are presented.

We

were completely entranced by these presentations—but I must confess that both

Nancy and I misinterpreted the nature

of what was being shown in this room! We

thought these were multiple studies Matisse had done for each painting, not

photographs of stages of the paintings themselves. (We do not read the descriptions on the walls

of these exhibitions; we look directly at the work itself and develop our own

reactions. Only later do we consult the

catalogues and/or online information to get the curator’s take on what we have

seen.) Although wrong about the physical

nature of what we were viewing, it turns out we were not so off about the

meaning and artistic nature of what we were looking at. As the online notes say,

Matisse embraced the opportunity to put

his process on display at the Galerie Maeght. He repeatedly insisted to Aimé

Maeght that the only point of the exhibition was to

present "the progressive development of the artworks through their various

respective states toward definitive conclusions and precise signs." The

photographs proved that the paintings were the result of a complex process. By

agreeing to make them public, Matisse tacitly acknowledged that their presence

added to the viewer's understanding and appreciation of his work.

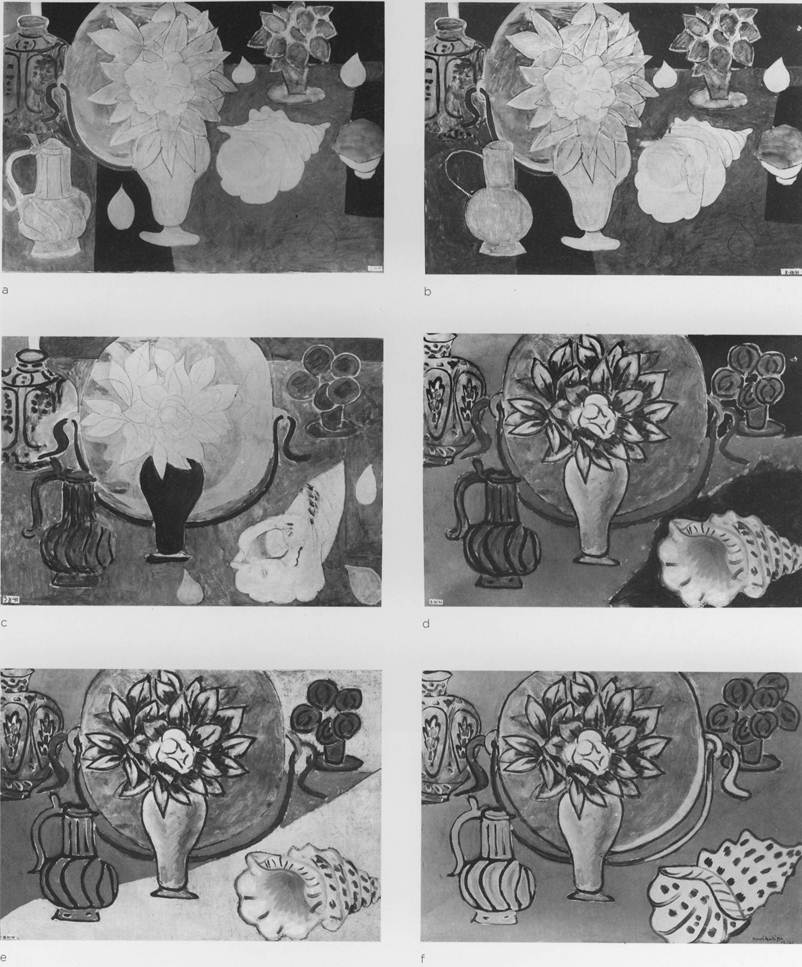

And

Dorthe Aagesen, co-editor

for the catalogue, wrote in one of her pieces in the catalogue, “Painting as

Film” (pp. 159f):

The photographs of Still Life with

Magnolia reveal how the painting gradually fell into place. Viewed as a whole, they may seem at first to

describe a linear progress towards a specific end, a movement toward

simplification and clarity as superfluous details are culled away, elements are

rendered more distinctly, and differences are accentuated so that each element

becomes a sign. Yet, upon close

inspection, they may also be viewed as a sequence of different—and, in

principle, equally valid—“takes” on how the final painting might have

looked. According to Marguerite Duthuit [Matisse’s daughter and often used source about his

works], her father had his works photographed only when he felt that they had

reached a certain stage of completion.

This suggests that in addition to capturing stages of the creative

process, the photographs were intended to capture different versions of a given

motif that had proved productive for that process. They may therefore be regarded as analogous

to the multiple canvasses that Matisse employed as he worked out various

versions of a painting.

The

least interesting of the three was his 1929 La

France (not shown here), a woman in a huge gown (described by the online

notes as “patriotic” and “dating to the early days of World War II.” The only thing of interest to me was the

subtle variations Matisse went through in the positioning of the woman’s arms

and elbows (which extend outward on both sides of her): at some stages they were more rounded in

overall form, at some more angular—but these minor variations greatly affected

the feel of the composition.

The

very most interesting was his 1941 Still Life with Magnolia (below).

The final painting is a good—but not great—one; but the process of

getting there was riveting. The online

note quoted him as having said, “He has put all of his strength into its

creation,” and that it was one of his favorites. Looking at the photographic record of the

stages of its progression (which we erroneously had taken to be separate

studies made for the final painting) was riveting: how it simplifies, combines,

changes emphasis; how problems appear and are resolved. I have included (below the image of the

finished painting) a reproduction of a page from the catalogue that shows all

six of the photographs of this painting included in the exhibit. We both we totally taken by “c,” the photograph

from 3 October 1941—and in particular by the way he has condensed the

representation of the flower and leaves into a marvelously draughtsman-like

composition. It was a version that we

both individually focused on as most exciting to each of us.

|

|

|

Still Life with Magnolia, 1941 |

a. 7 September, b. 8 September, c. 3 October,

d. 6 November, e. 18 November, f. (final) December

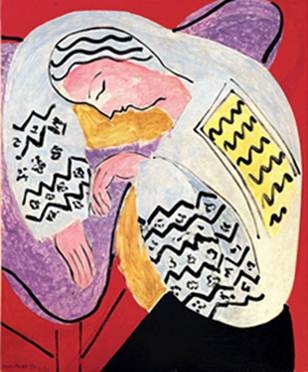

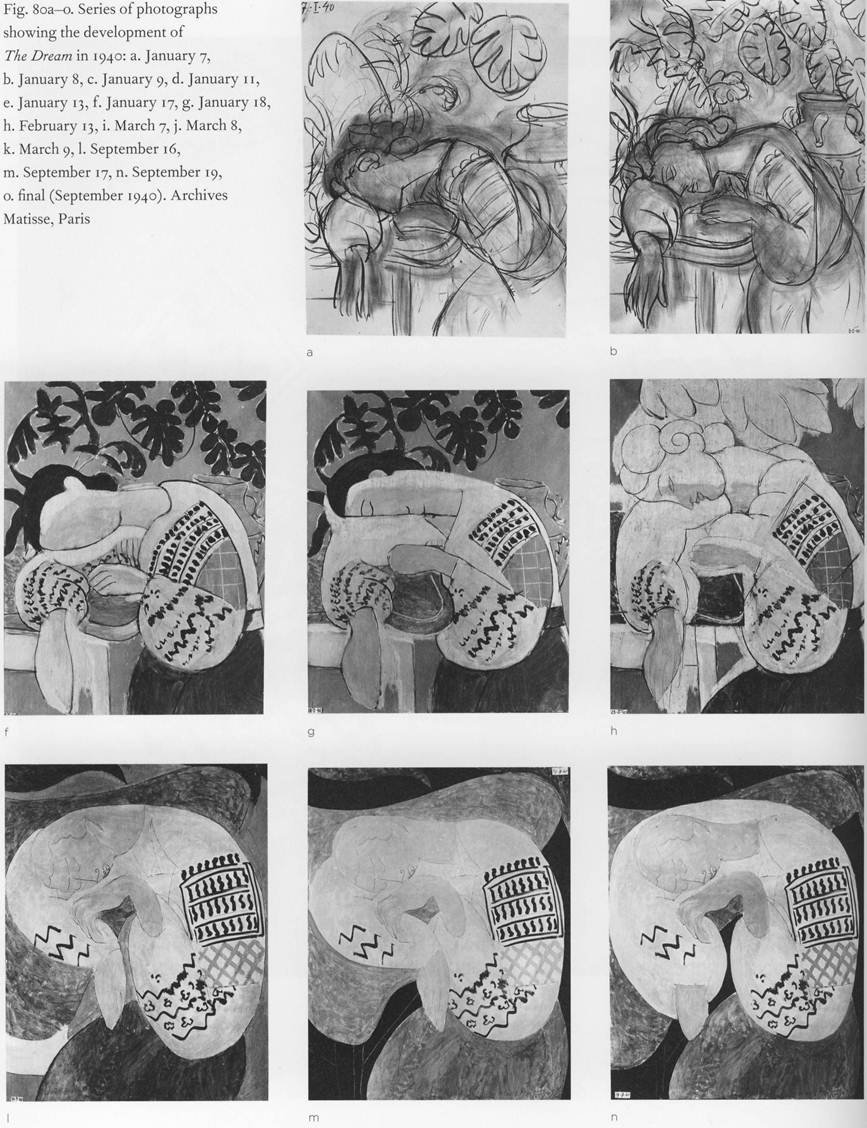

The

third, The Dream from 1940 (shown

below), is also more interesting for its progression than for its end product. There are 14 photographs (8 of which I have included

below the image of the finished painting) of stages of the painting studies,

taken over the period January-September.

I must say I completely fell in love with the very first, from 7 Jan,

which I incorrectly took to be a perfectly wonderful drawing in its own right. The online notes report that The Dream, “engrossed him for almost a year.

He told his son that at first it was ‘very realistic, with a beautiful woman

sleeping on a marble table amid fruit, [and it] has become an angel sleeping on

a violet surface.’"

|

|

|

|

Room Eight

During

the War, Matisse ended up spending time in Vence, in

Provence; as the online notes say,

Matisse had the opportunity to leave

France at the beginning of World War II. He refused. "I would have felt I

was running away," he said. Health problems necessitated major surgery in

1941, and he spent the following years recuperating; worrying about his wife

and children, who were active in the French Resistance; and working as best he

could. Matisse remained in Nice until summer 1943, when, as a precaution

against bombing attacks, he moved farther inland. He created his final painted

series during the five-and-a-half years he spent in Vence,

while living in a rented house known as the Villa le Rêve

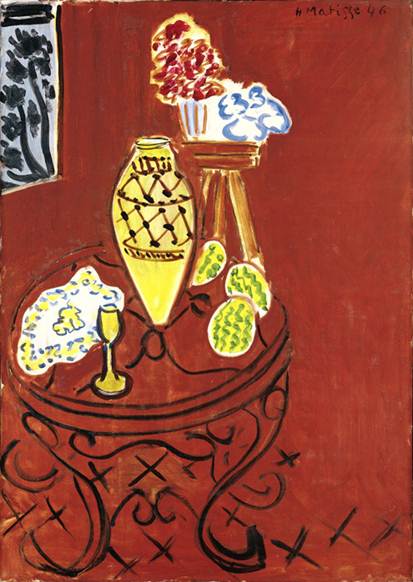

His

1946 Interior in Venetian Red (below), is a very simple still life which owes its specialness to

the off centered composition—two thirds of it is on the left half of the

painting—and the fact that the background is a rather uniform but intensely

rich shade of Venetian red. The effect

is quite stunning. Add to this the

playful abstraction of the evocation of the table and the floor tiles, and it

is a very effective work.

|

|

|

Interior in Venetian Red, 1946 |

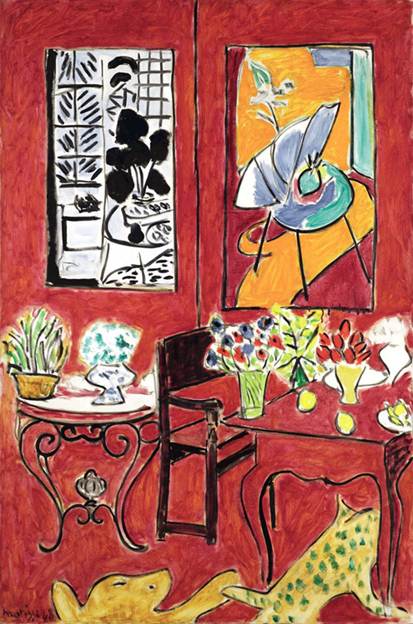

There

are three paintings in this room from 1948, all quite interesting. There is his rather playful Large Red

Interior, again wonderfully enhanced by the flattened walls (even across the

corner of the room) done in vibrant red—enlivened even further by the areas of brilliant

white, and the playful house pets in yellows at the bottom.

|

|

|

Large Red Interior, 1948 |

|

|

|

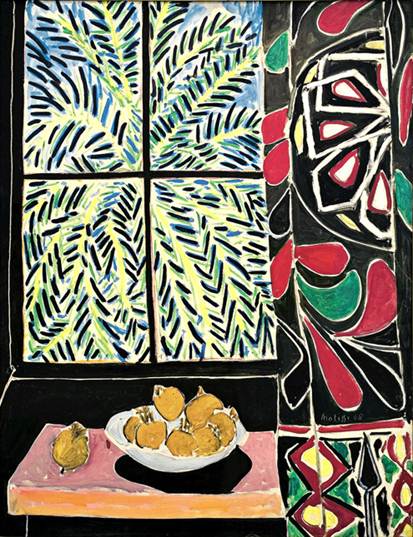

The second,

Interior with Egyptian Curtain (below), |

I am afraid would do better without its

Egyptian curtain—which makes it far too busy for my taste. The palm tree outside the window is fabulous—and

the pink table with its white bowl of fruit below the window is also wonderful. The fact that all of this is punctuated by

the mostly vertical diagonal if the curtain works quite powerfully—except the

brightly colored pattern of the curtain, while great in itself, seems

overpowering in combination with everything else going on in the painting. To me, a near miss at

greatness on this one.

|

|

|

Interior with an Egyptian Curtain, 1948 |

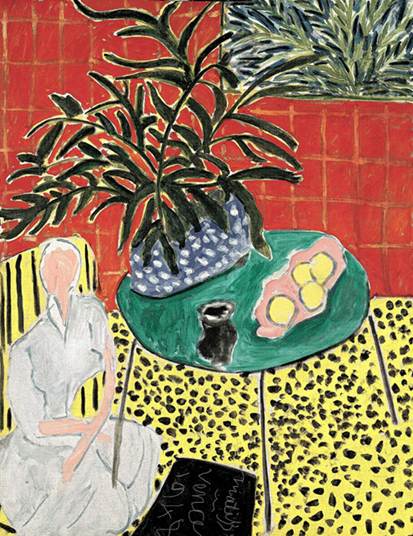

The

third painting from 1948, Interior with

Black Fern (below), is a very interesting painting, but also just a bit too

busy for my taste. Nevertheless, its

individual elements are quite wonderful—the red tiles of the walls, the bright,

speckled yellow of the floor and striped yellow of the chair, and the stylized

woman in white sitting in that chair, and not least of which being the whole

idea of a black fern.

|

|

|

Interior with Black Fern, 1948 |

![]()

Return to Dead Parrot homepage.