There is a fabulous and extensive exhibition of the art of Kurt Schwitters currently on display until 26 June 2011 at the Princeton University Art Museum (after that, it moves to UC Berkeley):

Kurt Schwitters: Color and Collage

OPEN Tuesday, Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday,

10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.,

Thursday, 10:00 a.m. to 10:00 p.m., and Sunday, 1:00 to 5:00 p.m.

Organized by the Menil

Collection in Houston (and exhibited there from 22 October 2010 to 30

January 2011) under the direction of Josef

Helfenstein and guest curator Isabel

Schulz, Kurt Schwitters: Color and

Collage is the first major U.S. retrospective of his

work since the 1968 show at MoMA. The

show contains an impressive array of important works from museums and private

collections in America and Europe, concentrating on the abstract assemblages, collages,

and sculptures related to his Merz concept—and including a

full-scale reproduction of Schwitters’ Merzbau. It is in Princeton

26 March-26 June 2011, after which

it moves to the

Those of you who— like Nancy (who excitedly discovered

Schwitters’s collages when she was already years into doing collages of her own)

and me (who, years earlier, had had the great fortune to go to the 1968 MoMA

retrospective of his work)—already know and love Schwitters, will immediately

recognize what a rare and wonderful opportunity this is. (We took the easy, one hour drive down to Princeton this past Saturday morning; but

the Museum is also easily reachable by

train: one takes NJ Transit from

NYC’s Penn Station to Princeton Junction,

transfers to the shuttle [the “Dinky”] to the

Kurt

Schwitters (1887-1948) was one of the outstanding figures in European modernism

at the beginning of the twentieth century, and together with Marcel Duchamp one

of the “father figures” for the generation of the avant-garde after the Second

World War. Equally gifted as artist and writer,

he began working in 1918 at the periphery of Dada and Constructivism on the

realization of his “Merz—a Total Vision of the World,” which to him was nothing

less than the integration of all forms of art. The syllable “Merz,” from Kommerz (meaning commerce), which in 1919 he cut out of an

advertisement for a bank and used for a label for his own unique position,

became synonymous with Schwitters himself, as applied to his entire oeuvre and

ultimately to himself.

Schwitters’s

Merz works exploded the boundaries of traditional genres and radically expanded

the possible ways of making art through the determined use of found materials…

(p. 7)

As the great Clement Greenberg wrote in 1959,

Collage was a major turning point

in the evolution of Cubism, and therefore a major turning point in the whole

evolution of modernist art in this century. Who invented collage--Braque or

Picasso--and when is still not settled. Both

artists left most of the work they did between 1907 and 1914 undated as well as

unsigned; and each claims, or implies the claim, that his was the first collage

of all. (in Art and Culture: Critical

Essays, Beacon Press,

According to Isabel Schulz in the

catalogue for the exhibition, “In addition to Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque,

Greenberg included only Arp and Schwitters among the ‘few great masters of

collage…’” (p. 8) Schulz writes,

After

1918, Kurt Schwitters contributed greatly to the establishment of the collage—the

“most revolutionary” pictorial practice of modernism… …Schwitters never stopped

thinking of painting as central to his work. To him, the two techniques were not mutually

exclusive but rather formed an integral whole. (Ibid.,

p. 51)

There is an elegance and subtlety

to the collages of Schwitters—and this applies to their colors as well as to

their composition. I am particularly

drawn to his earlier collages, in part because of their simplicity and purity,

but also because for me they achieve something quite sublime in their overall

effect. (Fortunately for me, this show is

particularly rich in collages from this early stage of his work.) I shall present below some examples of my

favorites from Kurt Schwitters: Color and Collage., Since I find that many people are not that

familiar with Schwitters’s work, I am going to present them here sequentially

rather than interspersed with text so as to allow for somewhat larger format

images, so as to maximize your ability to get some sense of how marvelous they

are. Of course, to get a true sense of

them, you need to see them in person—so, please consider a trip to see this

amazing exhibition. (There are several

museums that have extensive and significant examples of his work in their

permanent collections [e.g., MoMA in

NYC, the Tate Modern in

The first one I present—one of his

earliest collages, and the earliest in this show—is one of my very favorites due

to its subtle, dark, muted richness—juxtaposed to the brilliant blue form it

contains, partly painted, partly collaged:

Zeichnung

A 3 (Drawing A 3), 1918

Collage: paper on paper (5 ¼ x 4 ¼ )

Next, another simple but beautiful

little masterpiece from 1920, with a gorgeous, resonant shade of blue:

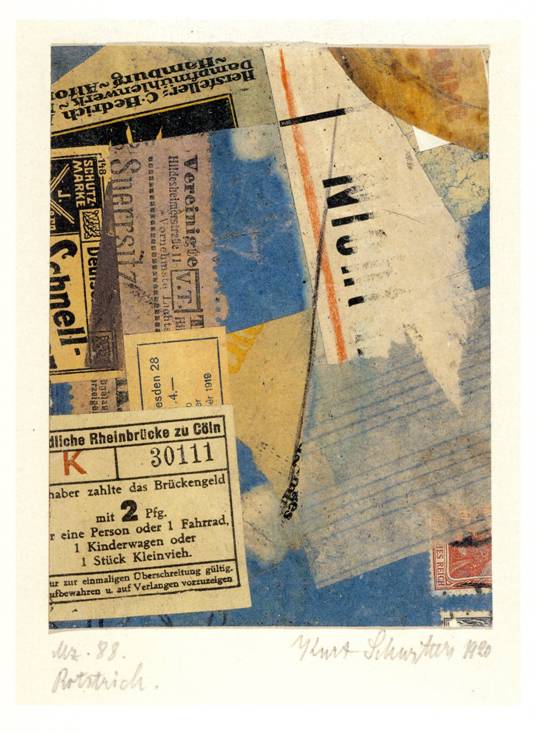

Mz. 88.

Rostrich. (Mz. 88. Red Stroke.), 1920

.Collage; printed paper and crayon on paper, (5 3/8 x 4)

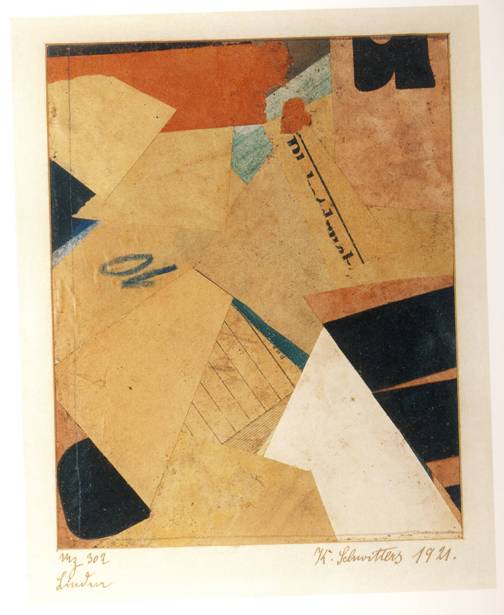

Another beauty from 1921,

Mz. 302

Collage; pen and paper on paper. (7 1/8 x 5 5/8)

Private Collection,

This particularly strong collage

reminded me very much of some of

![Kurt Schwitters Mz 371 bacco [Mz 371 bacco], 1922 Collage of cut and torn printed, handwritten, tissue, and coated papers on paperboard Sheet: 11; Image: 6-1/4 x Sheet: 7-1/2; Image: 4-7/8 inches The Menil Collection, Houston Photo: Hickey-Robertson, Houston © 2010 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn Kurt Schwitters Mz 371 bacco [Mz 371 bacco], 1922 Collage of cut and torn printed, handwritten, tissue, and coated papers on paperboard Sheet: 11; Image: 6-1/4 x Sheet: 7-1/2; Image: 4-7/8 inches The Menil Collection, Houston Photo: Hickey-Robertson, Houston © 2010 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn](Schwitter_files/image019.jpg)

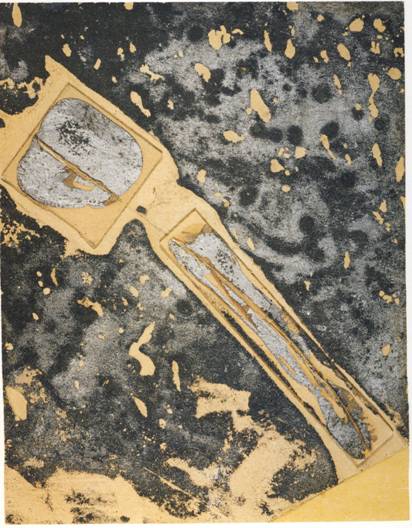

Mz 371 bacco, 1922

Collage; paper on paperboard. (6 ¼ x 4 7/8)

Menil Collection,

One of the things that distinguishes

the collages of Schwitters which I love from those that I do not like all that

much is their underlying compositional vision. It is my contention that many (and most of his

earlier works) are based on what Heinrich Wölfflin would have described as a

classical (with a closed, balanced, vertical and horizontal [or sometimes pyramidal])

composition, rather than baroque one (with an open, swirling, mannered,

non-linear composition)—and my preference always tends strongly toward the

classical end of the spectrum. To be

clear, even his most classical compositions have dynamic tensions distorting

the classical balance, but those tensions play against a strongly structured,

static foundation. These tensions are

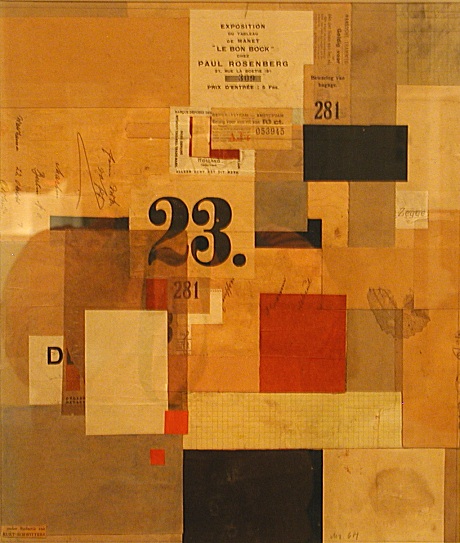

very visibly at work in the otherwise highly structured Mz. 601 below:

Mz. 601, 1923

Collage; paint and paper on

cardboard. (17 x 15)

In what I consider to be one of

Schwitters’s best large assemblages (many others of this type I find too

confused and clunky)—and one that I liked enormously—I see the other, more

baroque compositional vision. Even

though in this particular example I find the overall effect to be amazingly compelling,

it will serve as an example of the sort of vision I like much less in Schwitters.

(Since I am only presenting here

examples from the exhibition of ones I truly loved, I shall not show the type I

do not feel to work so well.)

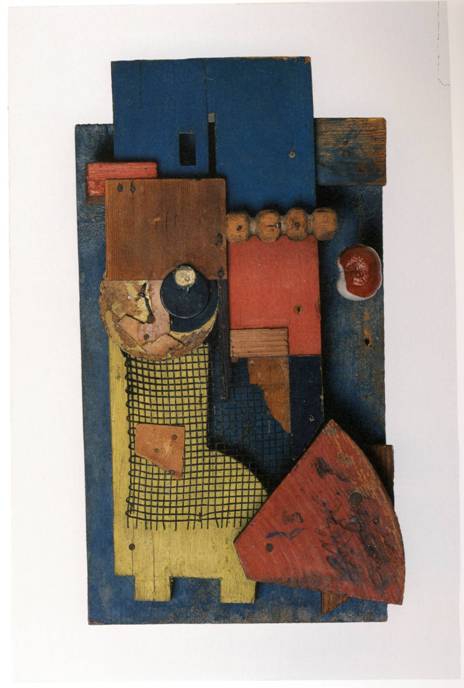

Ja-was?

–Bild (Yes-what? Picture), 1920

Assemblage; oil, pasteboard, cardboard, and wood on

cardboard. (38 5/8 x 25 7/8)

Private Collection

While in general I am far less impressed

with most of Schwitters’s sculpture, some of them are quite exquisite, as is the

elegant construction below:

Untitled

(Merz Construction, Top), ca. 1923-26

Relief; painted wood, wire mesh, cardboard, and paper

nailed on wood. (15 x 18 ¼ x 2 ½)

The Nazis considered Schwitters’s

modernism to be a “degenerate” for of art; and, in January 1937, Schwitters fled

I have already

hinted that I do not like his later work nearly as much as his earlier, but

there are many wonderful exceptions. One

unusual and entrancing collage—one of

the few in the show from his

Untitled

(Silvery), 1939

Collage; silver paint and cardboard on paper on tracing

paper.

There are many other forms of art

Schwitters engaged in represented in the show, from poetry to the “sound poetry”

of his Ursonate (1922-32); but I do not find these forms to my taste. The one project he created that I do find

fascinating, however, is his Merzbau. Starting in 1923, Schwitters began

transforming some of the rooms of his family home in

A reconstruction of one room of

the original

Seeing reproductions of art is

always a far cry from experiencing the real thing, but hopefully these images

will have provided a little taste of the wondrous experience of Schwitters’s

work. Get thee to

Here is a review of the show that

appeared in the New York Times of 31 March 2011 (www.nytimes.com/2011/04/01/arts/design/kurt-schwitters-exhibition-at-princeton-museum-review.html):

March 31, 2011

Versatile Collagist, Dangerous

Times

By HOLLAND COTTER

By

then Schwitters was living, self-exiled, in

An

application for a

The

facts of his late years are painful to contemplate, yet much of the art in

“Kurt Schwitters: Color and Collage,” a gift of a show at the Princeton

University Art Museum, feels just the opposite. Even when hermetic and

melancholic, as many of them are, the collages are a delight, transcending the

number-crunching, language-mangling modern world they reflect. And when they’re

joyous, they have a true in-love-with-life lift, with hints of nature blooming

through.

Inside

the first gallery, before you can even examine the art, you hear a semi-natural

sound, something between a thrush’s call and a cuckoo clock, then a kind of

Papageno’s song of mews, blips and nonsense syllables, broken by a military

rat-a-tat. It’s all Schwitters, performing his phonetic poem “Ursonate,” or

“Sonata in Primeval Sounds.”

For

decades he regaled European audiences with the piece, driving some listeners

from the room, leaving others in stitches. He made at least two recordings of

the piece and was still performing it in

Schwitters

made no categorical distinctions between his art (painting, collage, sculpture,

design, installation), his writing (poetry, essays, children’s stories) and his

performances. To him they were all integral parts of a one-man cultural

movement called Merz, which he invented, deriving the name from Kommerz, German

for commerce.

The

multidisciplinary nature of Schwitters’s output, which can make a career survey

look like a group show, may be one of the reasons he remains an underknown

figure. His sole American retrospective, at MoMA, was 25 years

ago. Representative samplings of his art have since rarely been on view, there

or elsewhere.

Yet

he has had a huge effect on post-World War II artists and is revered by many.

Two of the collages in the

Even

in his own time he was hard to get to know. He made contradictory impressions

on people who encountered him. To those who knew him through his performances

he was an extrovert: a large, hammy guy with big ideas and a big voice,

relishing the role of clown.

But

he could quickly drop into loner mode, shy away from company, rebuff unsought

friendship, assert the middle-class proprieties he grew up with. After bouts of

what seemed like compulsive extroversion, he spent long stretches on his own.

And the dozens of collages and assemblages at

Meticulously

puzzled together from paper, fabric, wire, scrap wood and other everyday materials,

these pieces are the work of a sorter and measurer, a concentrator, a tabletop

worker, someone who found satisfaction — more than that, comfort — in up-close,

fine-grained aesthetic control. Even the Merzbau, with its interior network of

nooks and shelves, projected deep focus, on a walk-in scale.

The

exhibition, which originated at the Menil Collection in

It’s

an unadventurous approach, with problems. No doubt the curators — Isabel

Schulz, executive director of the Kurt and Ernst Schwitters Foundation at the

Sprengel Museum in Hanover, Germany, and Josef Helfenstein, director of the Menil

Collection — wanted to correct a mistaken view of Schwitters as an

anarchic, antiart wild man.

But

reducing him to “primarily a painter” is also a distortion, and one too in line

with current, conservative market fashion. Still, it’s hard to complain about

any show that brings together as many wonderful things as this one does.

And

Schwitters did begin as a painter, and stayed one. Born in

At

the same time he was attracted to a new movement called Dada, which embraced

art and literature equally and strove to confuse distinctions between art and

life.

In

1918, under its influence, he made his first abstract collage from bits of torn

trash, including bus tickets, cigarette packaging, chocolate wrappers and

cloth, and then published a collage-style poem called “To Anna Blume.” To his

surprise the poem was a popular hit, too popular in the view of certain Dada

big shots who declared him ineligible for membership in their antiestablishment

movement. He didn’t care. He was far more interested in creating than in

rebelling. And besides he already had Merz.

The

1920s became a personal Merzathon.

Collages,

sculptures, prints and poems flowed. Schwitters met all kinds of vanguard

artists — friendly Dadaists like Tristan Tzara and Hannah Höch; Constructivists

like El Lissitzky; Theo van Doesburg, a founder of the movement known as De

Stijl — and collaborated with many of them. He traveled

A

good part of the

A

very early collage called “Mz 11 Strong Picture” from 1919 is a jumble of words

and numerals; a visual poem, tense and tight, like two cellphone conversations

in proximity, with one word, “stark” — the German word for “strong” — repeated

at different volumes.

In

other abstract collages, color and texture become content. This is true of “Mz

371 bacco” from 1922, with its bursting yellow and red tobacco label, its scrap

of handwriting like a whispered aside and its all-over surface pattern of

crackling and wrinkling. Similar effects become combustive in “Mz. 410.

Something or Other,” as cut-paper shards fly outward, fabrics unravel, and a

bird feather, stabbing into the composition’s center, seems to be exploding and

disintegrating.

These

collages have an ambiguous dynamic: they’re festive, but they’re not benign.

Thought of in terms of sound, they could be fireworks or gunfire. World War I

was just a few years in the past. The atmosphere of cosmic uncertainty it

generated was still very much in the air. For Schwitters, who was both an

adventurer and an elegist, drawn equally to the new and the old, who kept

dashing to the cultural front lines then pulling self-protectively back, art

making was a crucial stabilizer.

You

sense the steadying role it played for him in “Mz 601,” a 1923 collage radical

in its pre-Minimalist play of grids and classical in its precisely judged

asymmetries. And you sense it in the strikingly spacious, airy 1932 assemblage

called “Körting Picture.” Done during or after one of Schwitters’s repeated

getaways to a remote Norwegian island, it replaces urban detritus with a frond

of seaweed and a patch of bark, and adds flickering strokes of paint like

water-reflected light.

Overt

references to nature, to cloud-filled skies and forests, recur in the 1940s,

along with diminutive wood and plaster sculptures — surely Cy Twombly knows

them well — as personable as pets. But organicism in the late work more often

takes abject form. Collages grow denser and junkier, soiled with pigment and

dirt, affixed with lumps of matter as dark and moist looking as chewed food or

dissolving flesh.

Even

the immaculate-white Hanover Merzbau, in a much-traveled full-scale reconstruction

from the 1980s by the stage designer Peter Bissegger, feels claustrophobic and

tomblike. To Schwitters this precursor of contemporary installation art was

Merz in excelsis, a fit container for everything he cared about. But it isn’t

an opening-out, heart-gladdening utopian space. It’s the equivalent of a Joseph Cornell box: a

repository for relics, secrets and occult signs, a personal theater, and a

retreat.

No

wonder Schwitters was shattered by its destruction. (He started two other

Merzbaus, in

Kurt Schwitters: Color and Collage

WHEN AND WHERE Through June 26,

MORE INFO (609) 258-3788, artmuseum.princeton.edu.

EATING IN PRINCETON Blue Point Grill, 258

Nassau Street, (609) 921-1211, bluepoint.jmgroupprinceton.com; Elements, 163 Bayard Lane, (609)

924-0078,

elementsprinceton.com;

Olives Deli and Bakery,

“Kurt Schwitters: Color and Collage” remains

at the

![]()