Nancy and I just went this past Thursday to see a performance of On the Twentieth Century. We went with our friend David Rockwell, who did the amazing set design for this show.

This Roundabout Theatre Company revival of the 1978 musical, with book and lyrics by Betty Condon and Adolph Greene and music by Cy Coleman, is the tale of desperate Broadway producer/con man/womanizer, Oscar Jaffee (played by Peter Gallagher), running from creditors in Chicago fresh from his third consecutive failed production there (“It closed early.” “How early?” “Intermission.”), who is planning a comeback by enticing/seducing Lily Garland (played by Kristin Chenoweth), the brassy, insecure, temperamental former Broadway actress Oscar “created” (out of the accompanist audition pianist Mildred Plotka, “from the Bronx”), had a five year affair with, and who left him to become a successful film star in Hollywood, currently fresh from winning an Oscar. The seduction/recruitment and all that accompanies and ensues take place during the 16 hour trip from Chicago to NYC on the Twentieth Century Limited.

David’s incredible sets alone make this show worth seeing: they are exciting, entrancing, and gorgeous in their own right; they also perfectly set the tone for 1932 America and the iconic Twentieth Century Limited (the NY Central RR train that for years was the status means of luxury travel between NY and Chicago) with all the Art Deco style and period detail imaginable; and most of all, they create ideal environments to contain and express the human activities that dramatically take place within them—Rockwell is an accomplished architect, and the creation of such spaces is what architecture is (or, at least, should be) about. It always feels strange to praise an architect for creating space that is successfully designed to contain, express, and encourage the human activity it is designed to house, as this actually defines architecture as far as I am concerned; but, nevertheless, it is appropriate to do so, as so few architects succeed at this—and so many actually don’t even seem to try. David’s intense interest in theater sets (this season alone You Can’t Take It with You [also directed by Scott Ellis, who directed On the Twentieth Century], and Side Show, and the continuing successful hit musical, Kinky Boots), temporary structures (such as the amazing temporary TED theater he designed for Vancouver), and hotels and restaurants (we ate after the show in his dramatically successful Nobu 57…but that is another, delicious story) both express and encourage his exquisite interest in the nuance and power of human expression within specific environments, and have contributed to his being a grand master if this art.

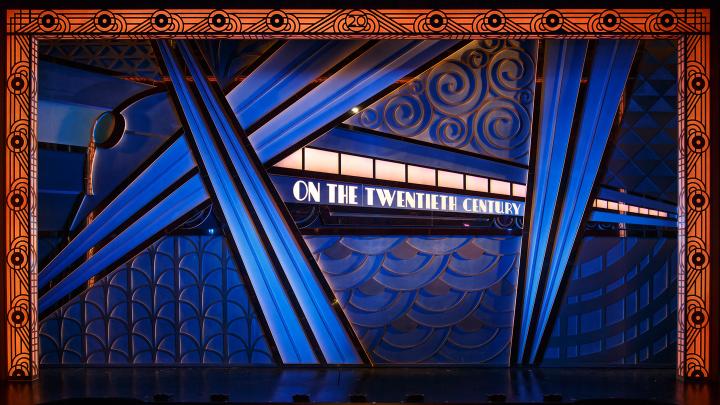

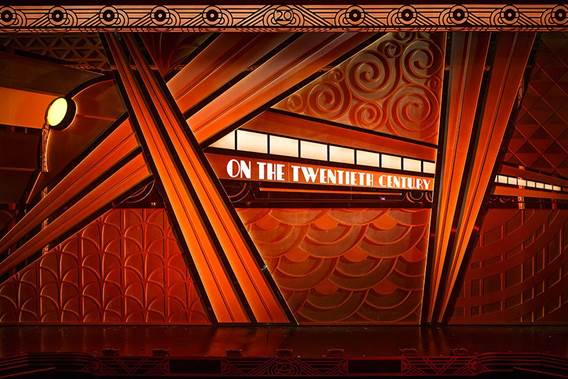

From the moment one enters the theater, the magnificent stage drop commands ones attention: it is a massive stylized representation of the train, dynamically expressing its rising energy in a diagonal thrust across the multiple fields of Art Deco patterns—one of which, one slowly realizes actually represents the smoke from the train’s engine.

This partly metallic tour-de-force sparkles with reflected light, without blinding its spellbound onlookers with glare. This stage drop makes numerous appearances throughout the course of the show, often looking quite different when lighted in different colors (the photo below is from later in the show)

—and, at times, actually appearing animated by the effective lighting by David Holder (whose successful lighting of the entire show is profoundly effective throughout the performance).

I consider Rockwell to be the reigning master of the stage drop: the one he did for You Can’t Take It with You was incredibly novel, powerfully effective, and artistically striking in an equally creative but totally different way.

The train on the stage drop is only one of many “trains” David creates for the show. The first scene in the Chicago train station features the metallic exterior of the train—beautiful in its incredible detail and impressive in its careful execution—and all the more unbelievable, given that it only appears for a couple of minutes. (The scene also has one of those profoundly evocative Rockwell renderings of a ceiling—in this case the steel and glass roof of the train shed—impressionistically invoked by the presentation of specific details.)

When this exterior is rotated 180 degrees, the interior of the car is revealed in all its Art Deco splendor. The fabulous, painstakingly accurate detail of this interior becomes the main setting for most or the ensuing scenes, although occasionally it withdraws up stage, receding into varying levels of subdued lighting, and, at times, almost disappearing.

There are two more trains: the one, a delightful miniature; the other an unexpected final transformation that accompanies the final denouement.

There are some other sets that reveal the breadth of Rockwell’s range: my favorite is a flashback scene of the audition during which Oscar discovered Lily, powerfully but minimally evoked with nothing more than an upright piano, a chair, and a drop consisting of a lowered batten from which is hanging some sandbags, ropes, and other rigging—these sparse elements against a dark background successfully create the audition environment in a way that is in sharp contrast to the rich detail of most of the sets.

On the Twentieth Century is something of a strange mix of a rollicking farce and an operetta. The original choice to follow an operetta musical style creates music that was challenging for me—although the energy of Scott Ellis’s skilled direction and the strength, energy, and power of the performances makes the play a thoroughly amusing and enjoyable experience—albeit one that is ultimately rather silly, in a fun way. Peter Gallagher bring power and comedic energy to the show in a way that would not work without his talent in the role; and Kristin Chenowyth gives a performance that is being viewed as the likely winner of this year’s Tony for best actress in a musical—and it is not clear who else could currently have been able to pull off this role, originally created in 1978 by the amazing late Madeline Kahn.

The supporting cast is also wonderful: Mark Linn-Baker and Michael McGrath give great performances as Oliver and Owen, Oscar’s partners in crime; and the octogenarian Mary Louise Wilson gives a most enjoyable performance as Letitia Peabody Primrose. We both found the second act more successful than the first; but, all-in-all, On the Twentieth Century is a fun evening of theater.

On the Twentieth Century is playing at:

American Airlines

Theatre

227 West 42nd Street, New

York, NY, 10036 | Ticket Services: 212.719.1300;

online

tickets

Return to Dead Parrot homepage.