Nancy and I just got a quick look at a fabulous exhibition

at the Asia Society of works by Wu Guanzhong—an amazing

painter we ‘discovered’ at the Hong Kong

Museum of Art during our trip to the Urban Age conference there last

November. (I am regretting more and more that I have not yet gotten to

write up our touring Hong Kong [although I did write up the conference proper: www.rickrubens.com/hk.htm];

it is really an incredible city.) I put ‘discovered’

in quotes, as it turns out Wu Guanzhong (吳冠中), who died at 90

in 2010, is an extremely famous

painter, considered by many to be the father of modern Chinese painting. His obituary in the Hong Kong South China Morning Post described him

as “one of the most important figures of 20th-century Chinese art”; and the NY Times just a few days ago ran an

article by Jane Perlez (“China

Extends Reach Into International Art”) which features

Wu and this exhibition.

We cannot wait to get back to the Asia Society to spend more time

in this great exhibition, Revolutionary

Ink: The Paintings of Wu Guanzhong, and I encourage you to do so as

well. It is on until 5 August 2012:

Revolutionary

Ink: The Paintings of Wu Guanzhong

24 April 2012 - 5 August 2012

725 Park Avenue (at 70th

Street)

New York, NY 10021

Tel: 212-288-6400

Hours: Tuesday - Sunday, 11:00 am - 6:00 pm, with

extended evening hours Fridays until 9:00 pm (except for July 1 through Labor

Day, when it closes at 6:00 pm on Fridays).

The Museum Galleries are closed on Mondays.

Wu Guanzhong went to Paris

to study at the École Nationale

Supérieur des Beaux-arts in 1947. He returned to China in 1950, bringing

with him many aspects of Western art, but returning to traditional Chinese

themes and techniques as well. He was sent to a labor camp during the upheaval

of the Cultural Revolution, and many of his earlier works were destroyed; his career

did not actually takeoff until the late 70s.

Revolutionary Ink: The Paintings of Wu Guanzhong, organized by the Shanghai Art Museum (to which Wu donated 113 of his works in 2008)

and Asia Society Museum, displays

examples of his work from the mid-1970s to 2004, focusing on his works in the

medium of ink. As the Asia Society’s

website notes,

It is notable that Wu began to work more

extensively in ink in the 1970s in his mid-career—turning to a traditional

medium at a time when most artists looked to western art for inspiration. The

exhibition traces the development of Wu’s work during this period with a

thematic focus illuminating the rich historical legacy of ink painting in

China, and also representing his radical individual style steeped in his strong

belief in formalist principles. Wu pushed the boundaries of our understanding

of how a traditional medium of ink can be made new for a new century.

I have included the complete website description and the Asia Society’s

press release at the end of this piece.

Here are some wonderful images from the show:

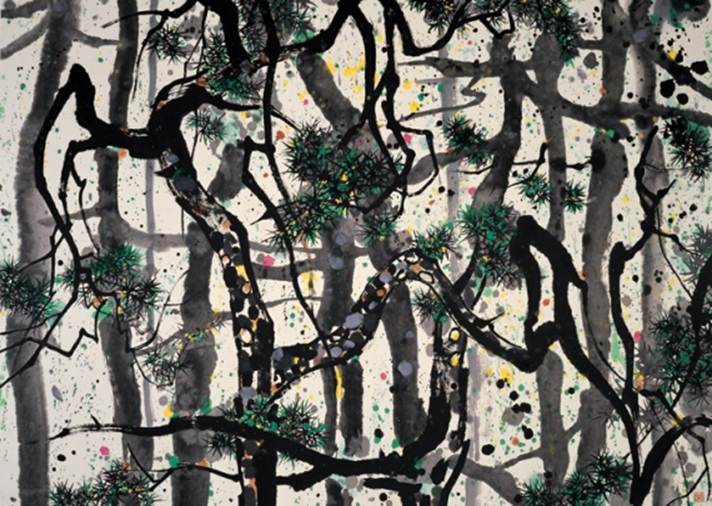

This one captures some of the vitality that Wu

introduces with his use of color:

Pines, 1995, ink and color on

paper, 140 x 179 cm, Shanghai Art Museum.

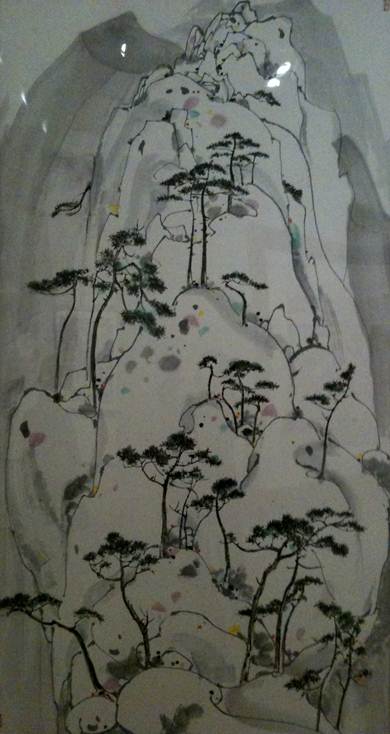

This one, which is the image

in the full-page ad that ran in Friday’s NY Times, is wonderfully reminiscent

of traditional Chinese landscape painting, yet at the same time so different in

its modernity:

Pines and Rockes in the

Lao Mountains, 1987, ink and color on rice paper, Shanghai Art

Museum.

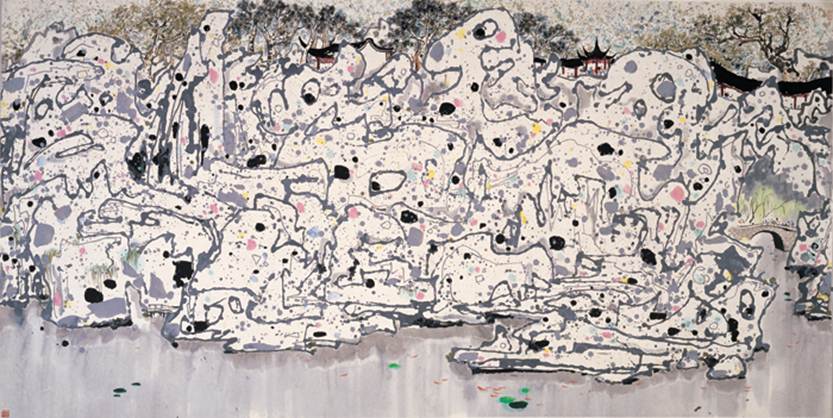

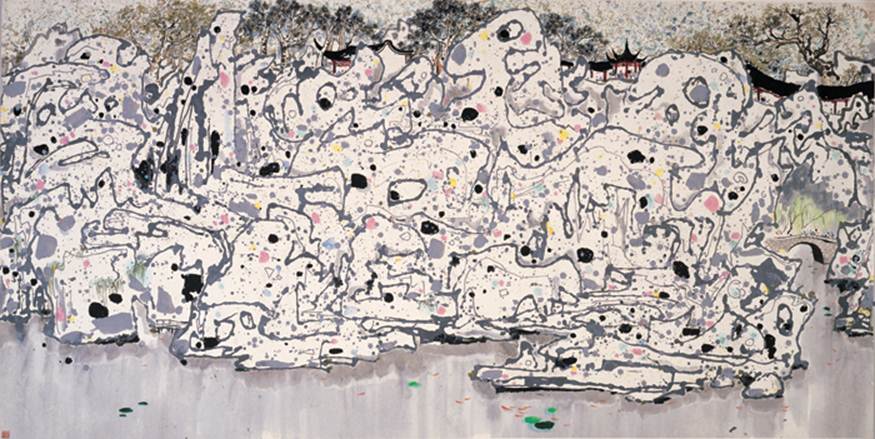

Lion Woods,

1983, ink and color on rice paper, 173 x 290 cm, Shanghai Art Museum

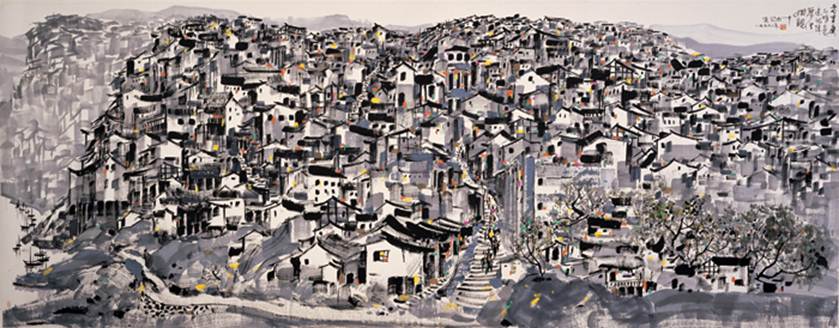

I particularly

enjoyed this cityscape:

Chongqing of the Old Times, 1997, ink and color on rice

paper, 145 x 368 cm, Shanghai Art Museum.

Here is one we loved from the exhibition in

Hong Kong:

Home of Man, 1999, ink and color on rice

paper, 69 x 69 cm, Shanghai Art Museum.

A Big Manor, 2001, ink and color on rice paper, 70 x 140 cm,

Shanghai Art Museum.

The Asia Society’s website description:

Revolutionary Ink: The Paintings of Wu Guanzhong

24 April 2012 - 5 August 2012

Wu Guanzhong (1919–2010) stands as one

of the most important artists of twentieth-century China. Born in Jiangsu

Province, Wu studied art at the National Academy of Art in Hangzhou (today’s

China Academy of Art) and, from 1947, in Paris at the École

nationale supérieure des

beaux-arts. He returned to China after three years and taught at the Central

Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing. His works were condemned before and during the

Cultural Revolution because his oil paintings did not comply with the political

interests of the time. In spite of this he continued to paint and emerged as a

national cultural figure whose works came to be celebrated inside and outside

China. He is also well known for his eloquent writings on art and creativity

that sometimes led to controversies and spawned heated debates among Chinese

artists and intellectuals. Wu Guanzhong created works

that embody many of the major shifts and tensions in twentieth-century Chinese

art—raising questions around individualism, formalism, and the relationship

between modernism and cultural traditions.

With a career spanning over sixty years, the selection of paintings in this

exhibition focuses on some of his best works in the medium of ink and spans the

decades from the mid-1970s to 2004. It is notable that Wu began to work more

extensively in ink in the 1970s in his mid-career—turning to a traditional

medium at a time when most artists looked to western art for inspiration. The

exhibition traces the development of Wu’s work during this period with a

thematic focus illuminating the rich historical legacy of ink painting in

China, and also representing his radical individual style steeped in his strong

belief in formalist principles. Wu pushed the boundaries of our understanding

of how a traditional medium of ink can be made new for a new century.

Landscape

Lion Woods, 1983, ink and color on rice paper, 173 x 290 cm, Shanghai Art

Museum

Wu Guanzhong often compared his revolutionary

approach to ink painting to the way a kite is navigated; not flying too far

from the ground. The use of ink and wash clearly reveals his solid grounding in

the centuries-old tradition of Chinese ink landscape painting. Monumental

mountains in Wu’s paintings echo the regal presence of mountain peaks in the

iconic landscape painting Early Spring by Guo

Xi (1000–ca. 1090), dated to 1072. Some other works by Wu show influences of

painters from the Song dynasty (960–1279) to the Qing dynasty (1644–1911) in

the compositions and the types of brushstrokes he uses to add a variation in

texture and an atmospheric effect. However, he has also created works that are

fundamentally different from the tradition, particularly in his use of bright

colors, liberal use of wash, and radical compositions based on an interest in

formalism. This section comprises several examples of drawings from nature that

Wu produced during his sketching trips throughout China and paintings from the

late 1970s to 2000 that trace his constant reflection on tradition and

experimentation.

Architecture and the Everyday

A Big Manor, 2001,

ink and color on rice paper, 70 x 140 cm, Shanghai Art Museum.

A Big Manor, 2001,

ink and color on rice paper, 70 x 140 cm, Shanghai Art Museum.

Where traditional ink paintings emphasized the grandeur and majesty of the

natural environment over small-scale pavilions or other architectural elements,

the most distinct compositions that Wu created are found in those paintings

depicting rural yet grand homes and towns that emphasize a constructed,

man-made environment. Rather than including buildings as a small part of

painting, he extracted geometric beauty and a structural rhythm from

architecture. To Wu, whether artists are painting buildings, mountains, rivers,

grass, or trees, it is of primary importance that they paint with feeling.

Abstraction

Alienation, 1992, ink and color on rice paper, 69 x 138 cm, Shanghai Art

Museum.

In his later period Wu’s landscapes became more and more abstracted. Most

of these works are from after 1990 and show an intention to represent states of

being, emotions, and concepts over more realistic representation. For example,

rather than showing birds-eye or long-view perspectives usually associated with

ink landscape paintings, the works provide a closer view as if the viewer is

fully immersed in the environment. On this subject he has said, “I want to

express the transformations in space and time that occur in my mind. The many forms

I see with my eyes inspire the unpredictable transformations that I haven’t yet

seen.”

Quotes from Wu Guanzhong

Select Quotes of Wu Guanzhong from Abstraction

and Form, Meishu (Fine Arts) in 1992, translated

by Valerie C. Doran for the exhibition catalogue Revolutionary Ink: The

Paintings of Wu Guanzhong (New York: Asia

Society, 2012)

"The beauty of abstract form is extracted from concrete objects and

distilled according to the intrinsic qualities of the form. The art of root

carving retains certain concrete aspects, and it is considered very beautiful.

This is called transforming the common and useless into the marvelous and the

quality of abstract beauty is foremost in creating this effect. On the other

hand, we also see some artworks that transform the marvelous into something

common and useless."

"The relationship between semblance and non-semblance is in fact the

same as the relationship between concrete and abstract. What exactly

constitutes spirit resonance and lifelike motion (qiyun

shengdong) in Chinese traditional painting? Whether

in landscape or in flower-and-bird painting, it lies in the expressive

difference between motion that has spirit resonance and motion that does not.

Within this there is the question of the harmony or conflict between the

abstract and the concrete, and the factor of either beauty or ugliness that

hovers just beyond. The principle of analysis for form is the same as for

music."

"The fundamental elements of formal beauty comprise form, color, and

rhythm. I used eastern rhythms in the absorption of western form and color,

like a snake swallowing an elephant. Sometimes I felt I couldn’t gulp it all

down and I switched to using [Chinese] ink. This is why in the mid-1970s I

began creating a large number of ink paintings. As of today in my explorations

I still shift between oil and ink. Oil paint and ink are two blades of the same

pair of scissors used to cut the pattern for a whole new suit. To nationalize

oil painting and to modernize Chinese painting: in my view these are two sides

of the same face."

"Brush-and-ink is misunderstood as being the only choice for life and

the future path of Chinese painting, and the standards of brush-and-ink painting

are used to judge whether any work is good or bad. Brush-and-ink is a

technique. Brushwork is embodied within technique, technique is not embodied

within brushwork, and technique is only a means that serves the artist in the

expression of his emotions."

"Whenever I am at an impasse, I turn to natural scenery. In nature I

can reveal my true feelings to the mountains and rivers: my depth of feelings

toward the motherland and my love toward my people. I set off from my own

native village and Lu Xun’s native soil."

This exhibition has been organized by the Shanghai Art Museum and Asia

Society Museum.

The curators of the exhibition are Melissa Chiu, Asia Society Museum, and

Lu Huan, Shanghai Art Museum.

Asia Society Museum Staff

Melissa Chiu, Museum Director and Senior Vice President, Global Arts and

Cultural Programs

Marion Kocot, Director, Museum Operations

Nancy Blume, Head of Museum Education Programs

Clare McGowan, Collections Manager and Registrar

Adriana Proser, John H. Foster Curator for

Traditional Asian Art

Jacob M. Reynolds, Associate Registrar

Miwako Tezuka, Associate

Curator

Davis Thompson-Moss, Installation Manager

Donna Saunders, Executive Assistant

Special thanks to Zixuan Feng and Renny Grinshpan, Museum Interns.

Contact:

Elaine Merguerian 212.327.9271,

elainem@asiasociety.org

ASIA

SOCIETY MUSEUM PRESENTS FIRST U.S. RETROSPECTIVE OF ONE OF CHINA’S MOST

IMPORTANT ARTISTS OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

REVOLUTIONARY INK: THE PAINTINGS OF WU GUANZHONG

On

view April 25 through August 5, 2012

Media

preview and private exhibition viewing: April 24, 2012 at 4:00 p.m.

Wu Guanzhong, Pines,

1995, ink and color on paper, H. 55.1 x W. 70.5 in. (H. 140 x W. 179 cm),

Shanghai Art Museum.

Revolutionary

Ink: The Paintings of Wu Guanzhong celebrates the sixty-year career of Wu Guanzhong (1919–2010), one of China’s most significant and

admired twentieth century artists. This first-ever major retrospective,

organized in collaboration with the Shanghai Art Museum, traces the artist’s

development in the medium of ink painting from the mid-1970s through 2004.

Exhibition works represent Wu’s radical individual approach that integrates

European modernism and abstract expressionism with traditional Chinese ink

painting.

Wu

lived in tumultuous times; persecuted during the Cultural Revolution at a time

when western art was decried, he was forced to abandon painting and he

destroyed most of his works in oil. However, he persevered, continuing to paint

and draw even when he was sent to the countryside for hard labor and

reeducation.

“Wu

Guanzhong is one of the most important artists of the

twentieth century,” says Melissa Chiu, Asia Society Museum Director and Senior

Vice President of Global Arts and Culture Programs. “He revitalized and

reinvigorated Chinese traditional ink painting at a time when most artists were

turning to western art for inspiration. We are grateful to the Shanghai Art

Museum for collaborating with us on this exhibition, which celebrates his

legacy as a modern master who pushes the boundaries of our understanding of how

a traditional medium like ink can be made new for a new century.”

News

Communications Department

725 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10021-5088

AsiaSociety.org

Phone 212.327.9271

Fax 212.517.8315

E-mail pr@asiasociety.org

Revolutionary Ink: The Paintings of Wu Guanzhong is

curated by Chiu and Lu Huan, Curator, Shanghai Art

Museum.

About

the artist

Wu Guanzhong, A Big Manor, 2001. Ink on

rice paper, H. 27 9/16 x W. 55 1/8 in.

(H 70 x Q. 140 cm), Shanghai Art Museum.

Born

in 1919 in Jiangsu Province, Wu Guanzhong enrolled in

the acclaimed Hangzhou Art School (today’s China Academy of Art in Hangzhou) in

1936. At the age of 27, he left to study in Paris at the École

National Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, where he studied

western painting traditions and methodologies. After three profoundly

influential years, he chose to return to China for patriotic reasons, to teach

at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing. Painting in oil, he developed

an original style that combined both traditional Chinese ink painting and

western techniques of watercolor and oil painting, and became a mentor to a new

generation of Chinese painters.

However,

his paintings, which were influenced by both western

art and formalism rather than the then accepted style of Social Realism, along

with his writings soon led to trouble with the authorities. As the Cultural

Revolution began in 1966, Wu destroyed most of his works before the Red Guards

searched his house and confiscated his properties. Wu was still heavily

persecuted during the revolution as a bourgeois formalist and was forbidden to

paint, write or teach for two years. He was sent to the remote rural

countryside and subjected to reeducation through hard labor. Yet in spite of

harsh living conditions, he continued to paint whenever he could, and

eventually was allowed to teach an oil painting class for the army in Hebei province.

Finally

in 1973, his living conditions began to improve when Premier Zhou Enlai commissioned him to paint a large mural in a Beijing

hotel. Wu was reunited with his family, and also around this time, began to

paint in ink. His resulting ink painting “Chongqing the Riverside City”

launched a new stage of his career in a country now more receptive to his

ideas. Somewhat ironically, Wu went against the tide in returning to ink at a

time when many of his students, most born in the 1950s, became greatly

interested in European and American oil painting and, they adopted subjects and

compositions of Western European art and experimented in styles as diverse as

surrealism and expressionism.

In

1978, at age 59, he had his first solo show since his return to China in 1950,

which traveled throughout the country. He continued to paint in ink, creating

landscapes distinguished by their expressive line and unusual application of

color. In 1985, an exhibition of his latest works was shown at the National Art

Museum of China in Beijing, followed by a solo exhibition at the British Museum

in 1992. Late in his life, he traveled widely throughout China and other parts

of Asia, as well as to Europe, to attend a series of his solo exhibitions and

to give lectures on those occasions. His prolific career as a writer on his

philosophy of art has produced numerous monographic publications in various

languages. Wu died in Beijing in 2010 at the age of ninety.

The exhibition

Revolutionary

Ink: The Paintings of Wu Guanzhong is organized thematically into three sections that

evoke Wu’s approach to the medium of ink and account for distinct genres of his

practice. Landscape, the first, emphasizes the ink and wash

painting tradition while showing the departure from tradition that some of his

work represents, for example, in the random use of color. The section comprises

paintings from the late 1980s and 1990s, representing views of high altitude

mountains in vertical format, or expansive horizontal landscapes, in which he

used ink to create an effect of flatness, in contrast to the traditional effect

of depth and vitality.

The

second theme in the exhibition is Architecture. Where traditional ink paintings

emphasized the grandeur and majesty of the natural environment over small-scale

pavilions or other architectural elements, Wu’s paintings depict rural yet

grand homes and towns and emphasize a constructed, man-made environment.

The

final section of the exhibition is Abstraction, representing Wu’s later period

in which his landscapes became more abstracted. Most of these works are from

after 1990 and show an intention to represent states of being, emotions, and

concepts over more realistic representation. For example, rather than showing

birds-eye or long-view perspectives usually associated with ink landscape

paintings, the works provide a closer view as if the viewer is fully immersed

in the environment.

Revolutionary

Ink: The Paintings of Wu Guanzhong is accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue with

essays by leading Chinese and American scholars. The exhibition begins a year

of programming at Asia Society in arts and culture, policy and business that

explores China’s past as a window onto its present and future. For program

updates, visit AsiaSociety.org/nyc

Exhibition

funding

Support

for this exhibition is provided by the Take a Step Back Collection. Asia

Society also acknowledges the generosity of China Guardian Auctions Co., Ltd.

Support for Asia Society Museum provided by the Friends of Asian Art; Asia

Society Contemporary Art Council; Arthur Ross Foundation; Sheryl and Charles R.

Kaye Endowment for Contemporary Art Exhibitions; Blanchette

Hooker Rockefeller Fund; National Endowment for the Humanities; Hazen Polsky Foundation; New York State Council on the Arts; and

New York City Department of Cultural Affairs.

About

Asia Society Museum

Asia

Society Museum presents groundbreaking exhibitions and artworks, many

previously unseen in North America. The Museum is known for its permanent

collection of masterpiece-quality works gifted by Mr. and Mrs. John D.

Rockefeller 3rd and a contemporary collection launched in 2003. Through

exhibitions and related public programs, Asia Society provides a forum for the

issues and viewpoints reflected in traditional, modern and contemporary Asian

art. Founded in 1956, Asia Society is a nonprofit educational institution with

new multi-million dollar, state-of-the-art cultural centers and gallery spaces

in Hong Kong and Houston, and offices in Los Angeles, Manila, Melbourne,

Mumbai, San Francisco, Seoul, Shanghai, and Washington, DC.

Asia

Society Museum is located at 725 Park Avenue (at 70th Street), New York City. The

Museum is open Tuesday through Sunday from 11:00 A.M. – 6:00 P.M. and Friday

from 11:00 A.M. – 9:00 P.M. Closed on Mondays and major holidays. General

admission is $10, seniors $7, students $5, and admission is free for members

and persons under 16. Free admission Friday evenings, 6:00 P.M. – 9:00

P.M.

The Museum is closed Fridays after 6:00 P.M. from July 1 through Labor Day.

AsiaSociety.org/museum

Return to Dead Parrot homepage.