DEAD PARROT’S GUIDE to FLORENCE (PLUS PADUA, VENICE, and ROME)

This

is my guide to Florence (with some

added suggestions about eating and touring in

and

[click on the name of the city to go directly to that section in this guide]). I have just updated it after our May 2013 trip to Florence and Venice. (It was originally written after our visit in April 1997, and it has additions and emendations as the result of our trips in April 1999, May 2003, and September 2006. It also includes schedules of hours {indicated within this sort of wavy brackets}, which, at least for Florence, were current as of the beginning of June 2013, but which change with some frequency—so, while a useful starting point, they are worth checking at the time of any visit.)

The guide is focused on the places

and people who led up to and then began the Renaissance in Florence; and, in

particular, the three men who worked in Florence together at the beginning of

the quattrocento (“[one thousand]

four hundred,” the Italian way of referring to the 15th century) and

created the architecture, painting, and sculpture of the period: Brunelleschi,

Masaccio, and Donatello (respectively).

These three men were friends (and, at least, Donatello and Brunelleschi

were close friends), were well-acquainted with each other’s work, and, probably

together at times, traveled to Rome to study the art of classical

antiquity. It provides a tour that is

roughly chronological, and, of course, can and should be rearranged to suit

where you are staying, the amount of time you have, the weather, your own

preferences, and the whims of your actual visit. Things in bold type represent those

extremely special places and objects that are ones I myself would visit multiple

times on any trip to Firenze. Things in [square

brackets] are places and activities I am not particularly interested in, and

would readily omit unless I had unlimited time—or interests different from the

ones I actually have. Items underlined

and in blue are links to places that have web sites of their

own (and can be clicked on to get there, if you are looking at this guide

online). The “*XX*” symbol indicates an unpleasant level of tourist

concentration. On this subject, there

are a few museums and sites in Florence that present difficulties in terms of

long lines to get in (most particularly the Uffizi Galleries), and I recommend

you consider purchasing either a FirenzeCard or a

membership in the Association

Amici degli Uffizi as a solution to this problem. (Since this is primarily an issue at the

Uffizi, I present a discussion of the problem and the options in the section

about the Uffizi toward the end of the Florence part of this guide.) I suggest you use as basic guidebooks for

general information, maps, other sites, etc., R. Wurman’s ACCESS: Florence and Venice and ACCESS: Rome (Harper Perennial), which are by far the best and most accurate (particularly

artistically). I have drawn art

historically on several scholarly works (at times, too heavily drawn on them,

were this intended as in any way a scholarly work): H.W. Janson, The Sculpture of Donatello

(Princeton Univ., Princeton, NJ: 1963); Bates Lowry, Renaissance

Architecture (Braziller, New York: 1965); Peter Murray, The Architecture

of the Italian Renaissance (Batesford, London: 1963); and, Charles Seymour,

Jr., Sculpture in Italy: 1400-1500 (Penguin, New York: 1966); and, on

the guidebooks just cited. Have you the

time, I recommend them all to you.

Santa Maria Novella One enters through through the garden at the

right of the façade of the church (the FirenzeCard entrance is around at the

back [railway station] side of the church) {Monday

- Thursday 0900-1730, Friday 1100-1730, Saturday 0900-1700, Sunday 1300-1700; Chiostro di Santa Maria Novella (Green

cloisters): Monday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday 1000-1600}- A Dominican church

(therefore very

large, to meet preaching needs), begun in

1246

(the façade is the

1470 work of Alberti).

This is the first Italian

Gothic church of Florence, and actually the first fully developed example of

this style anywhere.

The Italian Gothic style has certain connections to

the northern Gothic of France (which

physically entered Italy as early as 1135 in the form of the Abbey of

Chiaravalle, near Milan): the grandeur

and huge scale, the mystical and otherworldly quality of the space, the vaulted

masonry ceilings, and the pointed arches and groin vaults, themselves, are all

typically Gothic. There are numerous

distinctive differences, however: there

is always more structural presence in the walls of the Italian Gothic (whereas

the French opened the walls and filled them with stained glass); the supports

are more massive (compared to the tall, slender columns of the French Gothic);

there was no use of flying buttresses (which are necessary to thin down the

support members and open the walls in northern Gothic)—these spiky external

forms would have offended the Florentines; while there is great height, there

is not the emphasis on the verticality of the French Gothic—a strong horizontal

feel is evident in both the proportions and architectural detail (showing the

clear influence of the horizontality of the Italian Romanesque [q.v., below in discussions of Il

Battistero and of San Miniato al Monte]–as

well its use of decorative patterning in colored marble); the bays are

invariably deeper in proportion to their length (usually square) than in

northern Gothic, where they are invariably quite shallow; and, in general,

there is a greater relation to the equilibrium of classical antiquity than one

finds in the soaring feeling of French Gothic.

Interior: Italian

Gothic - a great, formative example of this style: check out the feel of the

space. Also note the use of dark gray

stone (pietra serena)

against white plaster walls—very Florentine.

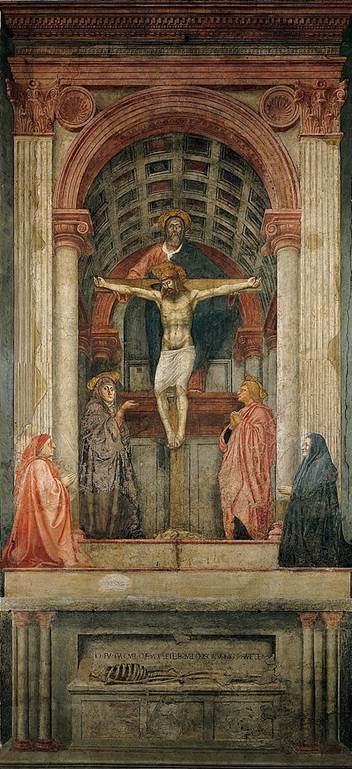

Holy Trinity: 1425 (this is way out of chronological sequence here: this is one of the pivotal works of the

Italian Renaissance, although it is in a church that was the first

fully-developed Italian Gothic building.) It is a fresco of the Holy Trinity (God the

Father enclosing Jesus on the cross, with the Holy Ghost as a necklace-line

bird between their heads) by Masaccio, on left side of nave, in the

middle. Note the classical architectural space he created for the scene (so

markedly different from the space of the church it is in) and the general

classicism of the references, the accurate use of linear perspective, the statuesque and sculptural nature of the human forms, the

emotion. A work of major

importance, here.

[Crucifix: Supposedly by Giotto;

in the La Sagrestia, off the left transept.]

[Cappella Filippo Strozzi: some frescoes by Filippino Lippi (who is good, but not nearly as good as his father,

Filippo Lippi—you have to look carefully at some of these names!), at right

front of the church.]

Chiostro Verde (“Green Cloister”): {

Monday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday 1000-1600} One now

enters through the church itself, through the garden at the right of the façade

of the church (the FirenzeCard entrance is around at the

back [railway station] side of the church).

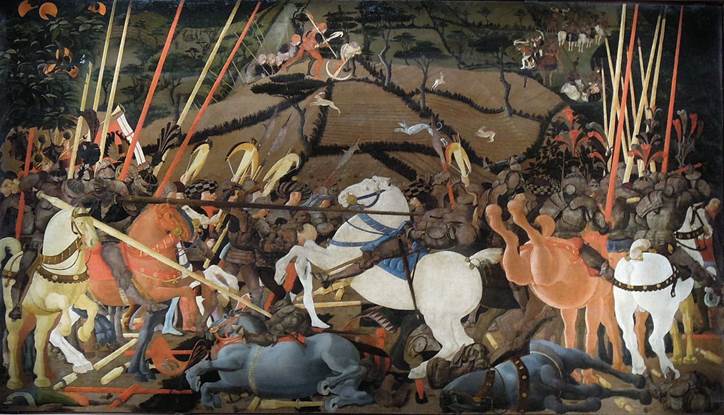

This relatively undistinguished cloister contains a fabulous

cycle of frescoes by Uccello—but,

unfortunately, as of this

visit, these marvelous frescoes are off somewhere being restored, and therefore

are not available for viewing. Many

of the frescoes were in poor condition; but the magnificent “Flood” fresco had been largely intact

and gave some sense of the genius of the artist. (I’m interested if any of my readers know of

any other work anywhere nearly this old that powerfully and realistically

contains a direct representation of weather, as this works so successfully

does.) I sincerely hope that the

restoration does justice to these wonderful paintings.

Il Duomo - Santa

Maria del Fiore - begun in 1294 (much of the design was done by Arnolfo di Cambio), this cathedral is

the heart of the city. (The photograph

below is one I took from the top of the tower of the Palazzo Vecchio.)

Exterior: late (19th

Century), but still an example of the Florentine love for pattern and, in

particular, for the patterned use of different colored marble—although this

example is pretty gaudy.

[Porta

della Mirandola, sculptural entry on N exterior wall: a very

interesting project containing works by all sorts of people, including

Donatello, but confusing without a plan]

Interior: Another

example of Italian Gothic style–again, get the feel of

it: it helps to then understand what is

going on in the changes that occur with Brunelleschi. Worth noting:

on entrance wall—3 stained glass windows by Ghiberti, and a big clock,

the hands of which move backwards.

(Access to the central space of the Duomo,

always interfered with by the volume of tourists, it now further restricted by

barriers which restrict access—and intensify the crowding.)

Dome by Brunelleschi

-1420-36 [One

can climb up into the structure of the dome, which ought to be interesting and

provide spectacular views of the city, but I never have done it. *XX*]

Beautiful proportions,

although more Gothic in design than he would have done had he not been

constrained by the pre-existing structure and underlying shape; and an

engineering marvel. The problem was that the

Florentines had constructed a cathedral so big (this has directly to do

with penis size and competition with the surrounding penises of Sienna and

Pisa, in particular) that they couldn’t figure out how to build a dome over the

140 ft opening they had created 180 ft off the ground. A dome is essentially an arch in three

dimensions (the construction of which is easier for us two-dimensional thinkers

to envision), and one builds one by first placing a horizontal beam across the

spring points of the arch and then building a frame in the shape of the arch to

support the stones until the keystone (the somewhat triangularly-shaped center

stone at the top) is put in place—at which point the whole thing is

self-supporting, and the framework can be removed. Since there were not many 140 ft trees in

Italy, this presented a problem. Brunelleschi finally came up with the

solution (inventing, along the way, machinery, construction techniques, and

materials to make it possible—examples of which can be seen in the wonderful Museo dell’

Opera del Duomo [ q.v., below], across the street behind

the apse of the cathedral): he designed

a dome that consisted of pointed sections, supported by 8 vertical ribs

(visible on the exterior). The structure

of the sections between the ribs was designed so as to be as light as possible: a lattice of minor ribs and open spaces,

contained between the two walls of the double shell Brunelleschi

constructed. The final solution to the

unsupported construction problem was to build the dome in horizontal units,

each roughly circular and self-supporting on top of the level which had just

been finished below it.

Il Campanile

(“The Bell Tower” - begun 1334) Called “Giotto’s”

because he was in charge of the construction for a period—but only because he

was Florence’s most famous artist. As a

painter, he actually contributed little to the plan or building.

Exterior: much better

example of Italian Gothic—still pretty over the top, but much more

beautiful. Note where the statuary is placed,

high up on the façade; but don’t waste time looking too carefully, as they are

only copies. (All of these very

important works are actually in the Museo

dell’ Opera del Duomo, q.v., below.)

[You can

climb up inside for the view, but I never have.

*XX*]

Il Battistero

(“The Baptistery” - 5th century, although the Florentines of the

Renaissance mistakenly thought it was a building from classical antiquity)

Exterior: good example

of Italian Romanesque (only better one in Florence is San Miniato al Monte, q.v., below): more horizontal and

squat, with the exterior shaped by the form of the interior space [not unlike

the Romanesque in northern Europe], but with a characteristic, Florentine,

patterned use of colored marble—done in a lovely, far less gaudy way,

however.

Bronze

doors: (It is not clear that any of the three

sets of doors are in fact real; I have never been able to get a

satisfactory answer to this question.

The east doors, Ghiberti’s

“Gates of Paradise,” most certainly are only copies; the real

ones are in the Museo dell’ Opera del

Duomo [q.v., below]. As for the rest, there is no other place to

see the real ones, even if these are only copies; so it’s worth a look here.)

[-South doors:

By Andrea Pisano, done in 1330. Basically International Gothic

in style, but with some marked influence of Giotto. Upper 20 panels are of the life of John the

Baptist; the lower 8 representing the virtues.]

-North

doors: (also the entrance to Il Battistero *XX*) Done between

1403 -24, these represent the project Ghiberti

won the right to do in the competition of 1401 (his entry in the

competition—better than any he did for the actual doors—is in Il Bargello (q.v., below), along

with that of the runner up, Brunelleschi.) The upper 20 panels depict New Testament

scenes; the lower 8 the 4 Evangelists and 4 doctors of the Church. (For stylistic comments, see remarks about

his competition panel in Il Bargello.)

[-East doors: copies of Ghiberti’s “Gates

of Paradise,” 1424-52. Copies of the 10 gilded bronze panels

representing Old Testament scenes. *XX*]

Interior: *XX* usually not worth the crowds; but, if

they are not too bad, there is the tomb of Anti-Pope John XXIII (Cardinal

Baldassare Coscia), done as a collaboration between Donatello and Michelozzo;

and the Romanesque decoration of the walls (especially the simplified animal

figures and geometric designs on the colonnade level) are lovely.

Piazza della Signoria

- a place you need to stroll through a couple of times, despite the crowds of

tourists to be found here.

Loggia

dei Lanzi - 14th century

Gothic loggia full of basically bad sculpture.

[-Ignore in front of the Palazzo

Vecchio the copies of Michelangelo’s David (the real one is in the Academia) and Donatello’s Judith and Holofernes (the real one

being upstairs in the Palazzo Vecchio;

and I am mortified that in the original edition of this guide I had

suggested that it might suffice to look at this terribly inferior copy).]

Palazzo

Vecchio (“Old Palace”) {0900-2400, Thursdays 0900-1400}

- done in 1298 by Arnolfo di Cambio

(you’ll notice this guy gets around: he

was the most important architect of the Italian Gothic in Florence).

The Palazzo

Vecchio once housed the government; Cosimo di Medici lived there for a

while in the 16th century, before his wife talked him into moving to

the Palazzo Pitti. Take a good look at

it and take a quick walk around inside on the ground floor, which is

interesting Gothic architecture—often full of beautiful flowers. Upstairs in the museum (which requires an

admission fee), you can stroll through the rooms of the Palazzo and take in the

interesting decoration of the rooms (although it is not worth focusing on any

particular part of it except the map room [near the exit on the third floor],

which is extremely interesting. Just

outside the entrance to the map room is what makes it really worthwhile

going into the museum level—Donatello’s

marvelous bronze statue of Judith and

Holofernes, ca. 1456-60, a great, totally free-standing work, which

combines multiple views into a plastic unity.

The

two figures are twisted and intertwined, and yet the action is curiously

restrained, given what is actually taking place, heightening the sense of

dramatic tension within the figures. The

pose—Judith with her left leg over Holofernes’ right shoulder, stepping on his

right hand, and her right leg between the legs of the seated Holofernes,

placing his torso between her legs (cf. with the pose of Donatello’s bronze David in the Bargello [below])—captures the sexual

aspect that is one side of the story; while her upraised sword and her

wrenching his head back and sideways to expose his neck to the impending blow

captures the rest. We spent over an hour

just looking at this one masterpiece from many different angles and

distances—and we did on many subsequent visits, as well. If you feel up to a very long climb, you can

walk up to the top of the tower and be rewarded with totally magnificent views

of the city and surrounding hills The view below is in the direction of the Bargello, the building in the center of

the foreground).

Loggia del Ospedale

degli Innocenti (“Loggia

of the Foundling Hospital”—out of chronological sequence here:

it should follow Santa

Croce, but since your visit there will also expose you to one of Brunelleschi’s important, developed,

later works [the Pazzi Chapel], it’s

important to see this first) —it was a

1419 design by Brunelleschi,

completed 1424. (It is the outside loggia

that is important; the rest of the building was done by Brunelleschi’s students.)

This

single example marks the true beginning of Renaissance architecture. (q.v., Bates Lowry, Renaissance Architecture.) It all begins here! Brunelleschi

has gone back to classical forms—rounded arches with a horizontal element above

them, Corinthian capitals, pilasters, and, behind, a vault that is formed by a

series of small domes (carried on the columns of the loggia and on corbels on

the surface of the hospital wall, creating square bays that are not

cross-vaulted as they would have been in a Gothic design, but purely classical

shapes) —that had not been utilized since antiquity.

He

has integrated these classical elements with elements of the Italian Romanesque

(e.g., using dosserets over the capitals) and some of its feel (e.g.,

the horizontal emphasis). It should be remembered, however, that Brunelleschi—like other

Florentines—believed these Romanesque elements were examples of

classical antiquity.) But he comes up

with a sense of lightness, rhythm, and rational “grasp-ability” that was new

and different from anything before it.

No distracting ornamentation, no mystifying and humbling sense of

inhuman scale—but rather an understandable, mathematically proportioned space

that feels immediately comprehensible by the viewer. Grand only in its

simplicity. One can detect the

influence of this design in the work of Masaccio

and Donatello—as early as in Masaccio’s Holy Trinity and the

niche Donatello and Michelozzo designed for Or San Michele,

both done in the mid-20’s.

Santa Croce {0930-1700, Sunday & holidays 1300-1700} (there

is now an admission fee charged to enter the church, but it includes entry into

the museum and Pazzi Chapel [q.v., below]; buy tickets around the

left outside wall of the church) Santa Croce is another major example of the

Italian Gothic by Arnolfo di Cambio,

begun in 1294. This is a Franciscan church

(absolute poverty as a principle—remember?), which was built in competition

with the Dominican

Exterior: Like so many,

actually 19th century.

Interior: Again, a very

Italian Gothic feel; but note the open timber ceiling (rather than having the

weight of masonry vaulting, this form is much lighter, permitting lighter

support columns that lend an airier feel), and the different proportion between

the nave and the aisle bays (bays are longer and shallower, giving a little

less typical Italian feel—but still unmistakably Italian).

Going

down the right aisle [quickly get by Michelangelo’s tomb *XX*] and arrive at–

Annunciation by Donatello: Toward the

apse end, on the right wall of the aisle of the nave is Donatello’s amazing Annunciation, done in gilded pietra serena (that gray stone mentioned

above), ca. 1428-33. Check out the marvelous composition: the balance of the angles and forms, the

movement from the angel to Mary—and yet the emptiness of the tension-filled

space in-between them, and the reaction of her body—startled and starting to

move away, but drawn back by the angel’s gaze (note the visual connection

between their eyes and faces), the emphasis on the dramatic moment.

Look

at her face—one of the few really beautiful female representations in the art

of this period; and look at her emotions.

And

do not ignore the compositional suggestion of the force of the angel’s

“message” to Mary—the intense triangular area of radiation from his center

outward towards her. The mutedly implied

sexuality is picked up in the placement of her hands and the folds of her

drapery. The sexuality—implied, denied,

and sometimes rather blatantly expressed—of this pointedly “non-sexual” moment,

is a very curious element in all Annunciation scenes [cf. the extremely un-sexual, but incredibly beautiful version by Fra Angelica in San Marco). Remember, this

is the moment that the Virgin is being “told” by the angel that she is pregnant

with Jesus; but is actually the moment of her immaculately being impregnated by

the Holy Spirit. Sexual

or non-sexual? You decide.

[Cappella Castellani: In right (west) side of the right transept;

frescoes by Agnolo Gaddi and his

pupils depicting the lives of the Saints.]

Cappella

Baroncelli: At the end of the right transept; frescoes by

Taddeo Gaddi (Agnolo’s father, and

Giotto’s pupil) of the life of the virgin.

The father’s work is much better than the son’s.

Cappella

Bardi and Cappella

Peruzzi: These two chapels are immediately to the

right of the altar.

The Cappella

Bardi, the closer to the altar, contains frescoes by Giotto

of The

Life of St. Francis; and the one farther from the altar, the Cappella

Peruzzi, contains The Life of Saint John the Evangelist—the best of Giotto’s work in Florence, although

they were badly damaged at one point, and their restoration was not altogether

well-done. (The only better Giotto frescoes—and they are much

better—are in the Cappella Scrovegni in Padova.) Although clearly a medieval

painter, Giotto represents a major

move forward towards the Renaissance; and, while not actually a part of the

Renaissance, his work has elements and implications that formed the major

influence in the tradition of Florentine painting that led eventually to Masaccio. Figures begin to have much more material existence

and corporeal presence in the painting of Giotto. He employed contour line, modeling, and

shading to create a sculptural presence in his figures. His people have far more personality than

those of any prior medieval artist, or any subsequent one for almost 100

years. He also demonstrates a masterful

grasp of composition: the arrangements of the elements to each other (and to the plane of the

fresco wall) is carefully integrated into the overall design. Each grouping within each fresco has its own

compositional integrity, and together they form a powerful and expressive

rhythmic whole. While apparently in better condition, the

frescoes in the Cappella

Bardi (e.g., The Stigmatization of St. Francis

below)

are

actually far inferior to those of the Cappella

Peruzzi—I suspect due to poor restoration work on those in the

former. In my opinion, the best of these

frescoes is The Apotheosis of St. John the Evangelist

(the lower panel on the right wall of the Cappella

Peruzzi, the chapel on the right).

The

action is framed and balanced by the two groups of figures, one on either side

of the main action, and each contained within its own architectural space. In contrast to this grounded and static base,

the center of the space opens to allow the movement of Saint John ascending

heavenward—rising through the opening architecture toward the angel coming

forward to receive him from above. Note

the personalities in the faces, the sculptural feel of the drapery, and the

beautiful use of color. The detail below

of

St. John from St. John on Patmos is a quite wonderful.

These two works, alone, merit spending significant time standing and

absorbing, as do some of the lesser works of these two chapels.

Crucifix

by Donatello: In the left transept. Ca. 1412, and thought

to have been done as part of a friendly competition with Brunelleschi. Wonderful, but difficult to

see well.

Cappella

Pazzi and Museo dell’ Opera di Santa Croce: (these are

now entered through the right side of the nave in the church itself, without

any separate admission fee)

Crucifix

by Cimabue: Although

tragically damaged in the flood of 1966 (the image below shows on the right a

pre-1966 photograph; the image on the left is in its current state), this

magnificent painting by Giotto’s

predecessor (and probable teacher) is quite moving. Cimabue

has far more Byzantine influences in his style (this Byzantine influence is characteristic of

the Sienese tradition of painting, by the way) than Giotto ever was

affected by, but his painterly quality and interest in the human form was

extremely important in Giotto’s

development.

St.

Louis of Toulouse by Donatello: (this statue—without its niche—is currently

at the Palazzo Strozzi in the Springtime of the Renaissance exhibition.) Niche and statue were done for the Parte

Guelfa to be placed on Or San Michele.

Donatello did them between 1422-1425;

and Brunelleschi’s influence seems

evident in the classicism of the elements of the niche (cf. the very Gothic niche Ghiberti made at the same time for Or

San Michele). Statue itself is done in fire-gilt bronze,

which, because of its size, required that it be constructed out of several

separate plates, assembled on a framework of metal bars—a totally novel

approach. Note the extraordinary drapery

of the clothing, hinting at the structure of the body underneath, and the

personality expressed in the face.

This

figure is radically different from most of Donatello’s

other works: it is calm and

contemplative, with an almost mystical air.

But this presentation fits the character of the subject: St.

Louis was a contemplative, holy man who renounced his kingdom to become a

friar.

Last

Supper by Taddeo Gaddi: Wonderful

fresco at far end of the room.

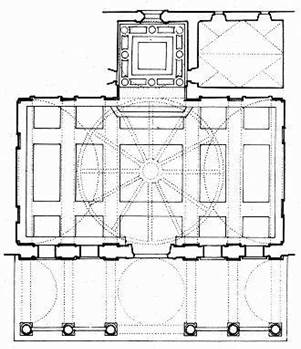

Pazzi

Chapel by Brunelleschi: This marvelous little building was planned in

the mid 1430’s by Brunelleschi (and thus is out of

chronological sequence here. If

possible, it is far preferable to see the Sagrestia

Vecchia at San Lorenzo before

seeing this later work—but, hey, you’re there now. ). It is a more complicated and

elaborate version of his plan in the earlier Sagrestia Vecchia (q.v., below), which consisted of a main

square area covered by a hemispheric dome, with a small choir with a similar

square shape covered by a dome.

Taking the radius of the dome over the central square here to be one unit, “r,” the sides of the central square are 2r in length. On the wall opposite the entrance, there is an opening for the scarsella (the altar), which is a square 1r on each side, and covered by a dome, the diameter of which is r. On either side of

the central square Brunelleschi added small ‘transepts’ which extend the width of the interior space ½r on either side of the central main square under the dome–effectively resulting in lateral areas equal to the opening of the scarsella (1r) on either side of the scarsella, and creating a total width of 3r. In elevation, the chapel is divided into two zones of equal height (2r each): the lower consisting of the flat side walls up to the top of the main entablature; the upper half being sub-divided by a smaller entablature into two equal zones of 1r each—the upper of these being the hemispheric dome, and the lower containing in the four corners pendentives, spherical triangles which transform the square into a circle to accommodate the circumference of the dome. The square scarsella space is balanced by a square entry vestibule outside the doorway, which is extended on the exterior by 1r square areas on each side—creating an overall width that is 3r (three of these units), and covered by a very classical, heavy barrel vault with a central, defining dome shape over the entry vestibule.

The thing that struck me on our most recent visit was that there is a tension in the rhythm of Brunelleschi’s building between twos and threes (and between threes and fours). Using the same unit “r” from the previous analysis, one could conceive of the building having a central area (or, for those who can handle all three dimensions, one could think of this in terms of volumes) 2r deep and 3r wide (this relationship being obscured by the way the floor is patterned—the three transverse units are there, although the outer ones are obscured by being subdivided in half, and the longitudinal ones are totally obscured by the centering of a 1r square under the dome, which results in two ½r rectangles on either end of that central square); and the longitudinal dimension increase to 3r if one includes the depth of the scarsella—creating an implied square, 3r on a side. There is also a 3r square if we envision the 1r x 3r area of the portico as part of the floor area—but that leads to a 4r x 3r total implied floor area if we then include the scarsella.

What

results is a space that exists in a mathematical relationship to its

constituent parts. This form results in

an almost musically harmonious feeling:

one is within a spatial harmony, with various overtones. The rhythms and harmonies are emphasized—and,

perhaps, over-emphasized—by the pilasters and trim on the walls and the

patterns on the floors–which are created by and therefore echo the underlying

mathematical relationships.

This

is a space that the human mind can grasp and be at peace with. It is stately and grand, but in a quiet,

stable, and tranquil way. Spend some

time just sitting in this space to get the feel of it. It’ll do you good! But the amount of decorative detail results

in its being not nearly as calming or successful as the less adorned, subtler

space of the Sagrestia Vecchia of San Lorenzo; and the decorative

patterning also serves to amplify the problems of the design. (If you are interested in the

problems of his design, look at the corners: he still hasn’t figured out how to deal with

the converging pilasters in a satisfactory mathematical way. [He doesn’t figure this out until Santo Spirito.] Also notice that there

are some minor discrepancies in the actual mathematical integrity of the

horizontal plan of the width of the chapel: he was forced to compromise the

exactness of some of these mathematical relationships in order to preserve the

continuity in the appearance of the decorative trim [essentially he had to

extend the vertical dimension to allow for the full width of the pilasters on

either side of the choir and the archivolt they support]—which, as Nancy

pointed out, was a good artistic decision.) The exterior, which was completed later by Brunelleschi’s students, is less

completely effective; but his basic plan is still in evidence and wonderful.

Special Note: Anytime you

are in the area of Santa Croce, don’t miss the opportunity to stop in at Vivoli

(via Isola delle Stinche 7r, between via Burella and via della Vigna Vecchia) to have the best gelato

in

Il

Bargello: (“The Captain

of Justice”) {open 0815-1650; Closed: 2nd & 4th

Sundays and 1st, 3rd, and 5th Monday of every

month} This trecento palace was the

first town hall, and the site of numerous public hangings. It also contains some of the world’s greatest

sculpture. Take in the look and feel of

the main courtyard.

Ground

Floor: Some lovely Michelangelo works: Brutus, Bacchus, the Pitti Tondo

(i.e., round medallion), and a David

(that isn’t so good); [also, lots of Giambologna,

if you are so inclined (actually, the Hermes

is quite wonderful); and Cellini, if you must.]

First

Floor: (go up outside staircase from central

courtyard, if it’s open [otherwise, use the stairs inside, across the

courtyard]; and take in architecture at the top of stairs. Then turn to your right to enter Sala di Donatello.) On your way out of the Sala di Donatello, it is well worth looking at

the bronze birds by Giambologna in the open balcony—they are truly

wonderful in a humorous, almost modern way, that always puts me in mind of Picasso’s ceramic birds, and especially

his owls. [There are

some other interesting things on this floor and the one above, but nothing

important.]

Competition

Panels: (On the back wall, to the right of S. Giorgio; but currently these panels

are at the Palazzo Strozzi in the Springtime of the Renaissance exhibition.) These are Ghiberti’s winning submission and Brunelleschi’s runner-up entry in the 1401 competition held to

award the commission for the north doors of the Baptistery. (There were many

other entries, all lost to posterity.)

The general form of the panels, and of the ones eventually on the doors,

is a Gothic motif—a quatrefoil; the theme was The Sacrifice of Isaac. The two finalist works are both incredible,

although Ghiberti’s is more the

ultimate culmination of what has been while

Brunelleschi’s is a somewhat rougher hint of what is to come. Spend some time taking in the two of them.

Ghiberti: The winner,

and deservedly so. This panel works

better: it is beautiful and powerful and

has a more polished style. His

composition uses the Gothic form of the quatrefoil to maximum advantage. There is more depth to the space he

creates. The strongly modeled figures

twist gracefully in a in rhythmic overlay that

represents the ultimate refinement of an International Gothic feeling. The angel sweeps forward out of the pictorial

depth. The mood is actually gentle,

given the subject matter: it represents

a pause in the action, reflected in the balance of the composition.

Brunelleschi: Also

magnificent, if not nearly as elegant. A

shallower, more rigid composition, with the figures and landscape elements more

sharply separated—in a way that lends an almost abstract quality to the

space. Note the focus on the intensity

of the human emotion (e.g., the expression of horror on Abraham’s face

as he moves into the action, and the fear in Isaac’s face) and on the crucial

moment of the action: the powerful

thrust of Abraham’s arm as he forces Isaac’s head back to expose his neck; the

knife poised at the moment of being thrust into Isaac’s throat; the force of

the angel coming in from the left, his outstretched arm countering the thrust

of the knife. The tension of the drama

is caught at its highest point. The

conception of human life with which this relief is imbued has far more to do

with what is to come in the Renaissance—and with the work of Donatello, in particular.

Donatello:

Marble David: (1408-9) Perhaps his first

major work. The idea of presenting David as the youthful victor over

Goliath may have originated here with Donatello. This is a work poised between the

International Gothic and the Renaissance:

its style is quite linked to the works of Ghiberti, and yet there are, particularly in the face, hints of individuality,

humanity, and classical beauty. Also,

more effeminate than one would have imagined David as being (note the similarity to the face of the Virgin in the Annunciation in Santa Croce).

St. George Tabernacle: (1415-17) Done for the Armorers’ Guild for Or San Michele.

Niche: The depth of

the architectural setting for San Giorgio was restricted because

the site it was designed for had a staircase in the wall behind which didn’t

allow for the same depth as the normal niches.

Donatello has used this

situation to marked advantage here, however:

he allows the shallowness of the space to project the figure out into

the space of the real world. (It has been suggested that

the statue originally held a sword in its right hand, which would have even

more dramatically projected the figure out into the space in front of the niche.) This figure

dynamically emerges out into the world in a way no other statue on Or San Michele even approaches.

San Giorgio: Strikingly

posed with his weight unevenly distributed towards his left foot while his body

turns toward the right, the statue conveys the sense of fear, doubt, and inward

struggle for decision to take action. And inward struggle, decision, and interior

crisis are what Donatello is most

wonderfully about. (My undergraduate

dissertation was about Donatello as

a creator of art imbued with a tragic sense of life—which, I believe, is all

about such inner struggle and taking action in a world in which rationality can

be sought, but in which not everything succumbs to the desire for rationality.) This young

warrior-saint is heroic, yet not without anxiety; his complex human emotion is

clearly evident in the dramatic moment of inner tension captured by Donatello. San Giorgio sees the task before him

and is summoning up his courage to confront it—but he is in no way certain that

he will prevail. The only certainty is

that he will undertake the task. Below I

offer two images of this fabulous sculpture, one from the left and the other

form the right, because on our most recent visit Nancy advanced the theory that

in the former there is a bit more resolve in his countenance, whereas in the

latter there is more doubt (and youthfulness); in any event, the effect is to

convey the combination.

The

Relief Sculpture: (Currently this relief is at the Palazzo Strozzi in the Springtime of the Renaissance exhibition; the

relief under the statue here is currently a plaster copy.) Don’t overlook the

incredible marble schiacciato (“flattened-out”) relief under the statue

itself: it is the representation of St.

George slaying the dragon. Here is a different dramatic moment, at the

height of the action.

Note

the incredible space and depth Donatello

has created in this very shallow, schiacciato relief (this panel is the first real

example of this form which was to become an important Florentine style): both through

the use of linear perspective in the building on the right (it is worth noting that

this example of linear perspective predates its appearance in any painting—let

alone any other sculpture—by a minimum of five or six years!) and through the use of chiaroscuro (light and shade)

and atmosphere (check out the wonderful trees in the background between St.

George and the maiden).

Notice

the horse, and especially how well he is able to sculpt its head using

virtually no actual depth at all on the relief plane. This schiacciato technique respects the integrity

of the surface of the relief in a way that creates a tension between actual

surface and pictorial depth that becomes increasingly important in Donatello’s later reliefs. Even the dragon’s cave is wonderful.

A

new speculation: On our 2003 visit to S. Giorgio, a radical

possibility occurred to us. We were

discussing the way Donatello has

used this sculpture actively to move out into the space in front of the niche

and to control and shape it. Having been

introduced to the Japanese architectural idea of the “stolen garden,” the way

an architectural construction can actually make use of the pre-existing

buildings and other features around it (a great example of this in Western

architecture is the way Mies van der

Rohe captured the surrounding space in his Federal Center complex in

Chicago—something which had been pointed out to us by Alex Garvin, who was accompanying us on this visit to Italy), I

raised the question whether it was perhaps possible that Donatello had done something similar here. We all agreed that he certainly was

commanding the space of the street—particularly with the powerful and riveting

gaze of S. Giorgio outward, obviously in the direction of the

dragon. We then went off to look at the

copy of the statue and its niche, in place on the exterior wall of Orsanmichele. Believe or not, at the exact point (both in

terms of angle and focal length) of S. Giorgio’s gaze, there is

round-arched doorway, articulated in rough-hewn stone, in a quattrocento house

at via Orsanmichele, 6!! Could it be

that Donatello was actually using

the architectural elements of the street as an implicit part of the sculpture

construction he was creating? Stand in

that doorway and look S. Giorgio in the eye, and then you

decide. But if he actually was using

that doorway to represent the dragon’s cave, it would be an unbelievably

radical example of the “stolen garden.”

Il

Marzocco: (“The Lion of Florence” - 1418-20) Distinguished by the

way the animal visage is suffused with the expressiveness and nobility of Donatello’s human forms—this is one

hell of a lion!

Bronze

David: (1430-32) This is the first

totally free-standing sculpture (intended to be viewed in the round as opposed to in a niche) and the first nude sculpture since classical

antiquity! While what is most

immediately striking about this David is that he is presented as a

highly erotic, extremely effeminate, beautiful young boy, note also the

tremendous classicism of the form and pose.

Also, the specific proportions of the figure exactly replicate those of

the norm in classical

Niccolò

da Uzzano: (ca. 1460-80) Very moving human depth in this

bust.

Crucifixion: This very

late (ca. 1470-80) bronze relief was probably designed by Donatello, as it has some of his feel; but it was almost certainly

executed by his students, as it just isn’t quite up to his standards in certain

important ways.

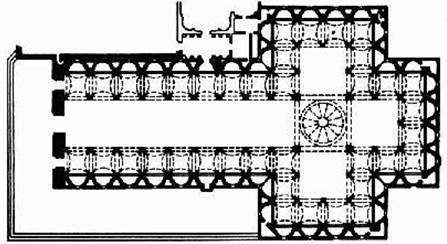

San Lorenzo: {1000-1650;

Closed: 2nd & 4th Sundays and 1st, 3rd,

and 5th Monday of every month} Brunelleschi

did his design for this church starting about 1419, although much of the work

on it did not get done until the ‘40s, and it was not completed until long

after his death in 1446.

The

basic type of the church is quite closely related to that of the Italian

Romanesque: the flat roof of the nave

rising above the aisles, the aisle bays are topped with simple domes, the use

of dosserets above the capitals.

The

details, on the other hand, are elements straight out of classical

antiquity: the pilasters, the elegant

columns, the capitals, the coffered ceiling.

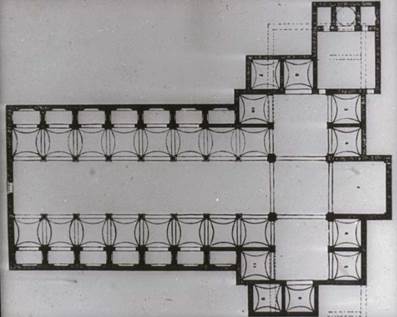

The precise mathematical harmonies of the space are pure Brunelleschi, however: the domed crossing of the church is a square

unit that is repeated on each side to form the transept,

and

repeated behind the crossing for the choir; the nave consists of four of these

units, flanked by 8 square aisle bays on each side—each one half the side of

the major square, and, naturally, one fourth the area.

(For

those who like the problems: the fact

that the side chapels were so high off the floor meant that, in order to have

the columns be the same height as the pilasters on the side walls, he had to

utilize very large dosserets over the capitals to make up for the difference in

elevation; he solves this problem at

Santo Spirito.) Here, once again, we are in one of the spaces he

created that is both light and grand, understandable

yet impressive, rhythmic yet stable; and the trim and architectural decorations

all combine to enhance these effects.

Twin

Bronze Pulpits by Donatello: ca. 1460-66 (on both sides of nave at front)

South

Pulpit: (on right; at the moment this pulpit is being

restored [interestingly, on site, where it normally stands in San Lorenzo, but not in public view.)

This is an incredible masterpiece. The

side facing in towards the nave is a Resurrection,

in which Jesus harrows Hell and then rises.

The picture of Jesus is unique in all of the art of this period: one can see the human dimension of his

struggle and suffering.

He

does not rise from his time in the underworld triumphant and untouched (as in

the typical iconography): rather he is

haggard, weary, and tattered from what he has endured. Jesus drags himself out of Limbo, his face

drawn and his eyes squinting from the strain.

It is a vision that is unique even for the Renaissance: it is not a picture of the triumph of reason,

or of the victory of human (or divine) striving over all obstacles; it is a

picture of the most intense striving against forces that do not so easily yield

to these efforts. Again, it is a tragic

view of life.

North

Pulpit: (on left) Crucifixion

stories. Note particularly the marvelous

architecture spaces created in the reliefs and the way they frame, emphasize,

and enhance the action. One of the most

wonderfully unusual reliefs on this pulpit, Christ Before Pilate, Donatello treats the psychology of the theme of Pilate in a totally

anomalous way: Pilate is usually

represented as evil (and often portrayed as in league with the devil), and

sometimes represented as a saint (as in the Ethiopian Church); but Donatello, always attuned to the nuance

of moral dilemma in the human situation, treats him as an individual facing an

impossible decision.

His

“alternation” and indecision is represented by the extraordinarily unusual

symbol of the servant who is bringing Pilate the water with which he will

eventually ‘wash his hands’ of the situation:

this servant, immediately behind him, is presented as a two-faced Janus

figure.

In

this unprecedented iconographic departure, Donatello

is clearly emphasizing the indecision and moral dilemma Pilate faced in making

his judgment: he found no evil in Jesus,

yet he was unable to dispute the charges of his accusers.

Sagrestia

Vecchia: {now open whenever the

main church is} Brunelleschi’s Old Sacristy (entered from the left

side of the transept) If you are like us, you will want to be able to

be inside this architectural masterpiece for the better part of an hour or more. The plan was

done in 1419, and the actual building was done 1421-1428, well before the rest

of the church, and therefore really a building in its own right. It is the first centrally planned

building of the Renaissance—and it is a true marvel.

The main area is a square with a hemispheric dome over it. Assigning “r” as the radius of the dome, the

sides of the square are 2r in length. The one side is divided into thirds (each

section therefore being 2r/3 in width), the central one being opened up to form

the entrance to a small altar, which itself is then a square (2r/3 on a side)

with a hemispheric dome (radius=r/3). The main space is horizontally divided

into three elevations: the lowest level consists of the side walls, which rise

flat up to the entablature; the middle level consists of the continuation of

the side walls up to the level of the springing of the dome—the four corners of

which are formed into pendentives, spherical triangles which transform the

square into a circle to accommodate the circumference of the dome [It has been

speculated that this particular section of Brunelleschi’s

design may have been influenced by his friend, Donatello, who also did the round reliefs that decorate the four

pendentives.]; the third is the hemispheric dome itself. The dome is, of course, 1r in elevation, as is

the middle level with its pendentives.

There are many claims made as to the elevation of the lowest level and

its relationship to the whole—all of them erroneous! [The people at the church

itself claim that the building consists of two cubes (of 2r on a side) on top

of one another: the top one consisting of the upper two sections, and the

bottom one consisting of a cube in its own right, therefore claiming the

elevation of the lowest level to be 2r. One scholarly work by Peter Murray

claims (and has a diagram to demonstrate it) that the lower two levels

form a cube—with the elevation of the whole being divided into three equal

heights of 1r each.] On extremely careful observation, Nancy and I are

completely convinced that the height of the lowest level of the space is, in

fact either 2r/3 or 3r/4 (it being impossible to estimate any more closely than

that); but that it is definitely not either 1r or 2r. The pilasters

which carry the entablature are modified Roman forms, much like those Brunelleschi used in the Loggia of the Foundling Hospital. Springing from the tops of the pilasters on

each of the four flat surfaces of the middle elevation are pairs of

semicircular archivolts, with radii of 1r and r/3.

But

what is going on in this building goes far beyond the mathematics of the

underlying relationships: just as the

mathematics underlying musical composition are only implicit in the actual

experience of the music when heard, it is the magnificent feel and experience

of this space that matters. The space Brunelleschi creates is truly

encompassing in a way that is not at all overwhelming. This is a space designed to be grasped

by the people in it: it is

understandable, comfortable, yet inspiring.

Once again, I return to a musical metaphor: the mathematical interrelationships are

experienced as harmonious, even without one’s direct consciousness of their existence. (In his latter version, the Pazzi Chapel, Brunelleschi’s use of ornament makes these relationships more

insistently present in the experience, in a way that makes it not nearly as

effective or successful as it is here.)

It is a space that has been created by man’s rationality, and it feels

understandable to those in it. Here is

truly a place to spend some time in order to absorb the feel of what the

Renaissance is all about

.

Donatello’s

Pendentive Sculptures: These scenes from the life of St. John the

Evangelist (Vision on the Isle of Patmos, Raising of Drusiana, Liberation

from the Cauldron of Oil, and Apotheosis) are done in painted

stucco, and were probably executed in the mid-1430s. They are great examples of Donatello’s ability to create space both architecturally and

through subtle shading and painterly suggestion, and have it function in real,

impressionistic, and symbolic ways. (It is of great importance to note that Donatello very early on had mastered the principles of linear

perspective, but that he often purposely violated their rules to achieve

particular effects—often for thematic or dramatic reasons.) While all

four reliefs are magnificent, the Apotheosis

is by far my favorite.

The

strong horizontal base (which projects forward in the foreground of the space

across the bottom of the relief) creates a solid grounding upon which the

action occurs. In the next level, the

figures are contained within the highly symbolic architecture. But this very containing architecture itself,

through the exaggeration of perspectival effect, leans inwards to emphasize the

movement of the main action, which is that of

Other

Sculpture by Donatello: The bronze

doors of the martyrs and of the apostles; the reliefs in painted stucco over

the doors of Saints Stephen and Lawrence and Saints Cosmas and Damian; Four Evangelists

(about which there is much question as to the artist); there is also an

absolutely beautiful bust of San Lorenzo on a counter on the entry wall

(despite the magnificence of this piece, its attribution to Donatello has been

severely questioned.)

Cappelle

Medici: *XX* One enters through the back of

Sagrestia

Nuova: Begun by Michelangelo in 1521 and completed

by Vasari in 1555, it is architecturally restful after the Cappella Principi,

but not in comparison the Sagrestia Vecchia of Brunelleschi. Some good Michelangelo sculptures: Dawn and Dusk (on Lorenzo’s tomb) and Night

and Day (on Giuliano’s tomb, opposite).

If you check out the female anatomy, you realize the big M wasn’t

terribly into the female form. There is

also a Madonna and Child by him.

Museo di San Marco:

{Monday-Friday 0815-1350; Saturday & Sunday 0815-16:50; closed 1st, 3rd, 5th

Sundays of each mo., and 2nd, 4th Mondays} The (eventually Dominican)

church and monastery of San Marco, built in 1299, were the home base of Fra

Angelico (and Savanarola, too). As

such, it houses the best, most loving, beautiful paintings he ever did. While Fra Angelico (cited as “Beato [Blessed]

Angelico” in this museum) is not part of the same humanistic spirit that lay at

the heart of the Renaissance, his paintings, particularly here in his own

monastery, are so wonderful and sensitive that they bear special attention

(look particularly closely at the faces: not the monumental humanity of

Masaccio and Donatello, but a spiritual beauty, instead). On the ground floor, immediately to the right

as you enter is an area that houses twenty of his magnificent works. There is also a wing that houses architectural

fragments from various sites in

Also upstairs are the monks’

cells—many with frescoes done all or in part by the master (see cells numbers

1, 3, 6, 7, and 9, using Access: Florence to guide you).

Museo dell’ Opera del Duomo:

{0900-1930, Sunday 0900-1345} This may be my favorite place in Florence, and it

is definitely not on the tourist itinerary, which is a great plus. It contains all of the great sculpture that

had originally been on the Duomo, Baptistery, and Campanile–much of which was

done by Donatello. It has been recently

been completely renovated, most successfully.

It is now beautiful even as a modern exhibition space.

Ground

Floor:

Brunelleschi Memorabilia: Fascinating

collection of things made, designed, and used by Brunelleschi in constructing the dome, including a model for the

dome itself.

Sala

dell’Antica Facciato del Duomo: (Room of the Old Façade of the Duomo) Various sculptures

and architectural details from the old façade, including works by Arnolfo di

Cambio (architect for the Duomo and many other Italian Gothic buildings in

Florence), and

Nanni

di Banco: Marble statue of a seated St.

Luke (1408-15) by this contemporary of Donatello. He was an important reviver of

ancient Roman forms, and therefore valued the effects of weight and mass in

sculpture. This work is quite wonderful–note especially

the tilt of the head, the face, and the way the lowered eyes create a look that

meets and holds your gaze.

Donatello: Seated St. John the Evangelist

(1408-15). This work was clearly

designed to be seen from below, in a way that the Nanni di Banco’s was not.

The placement of the niches for these works was to be slightly over the

head of the observer (here they are at least placed at a relatively elevated

position which, while not high enough to recreate the original effect, is much

better than the low placement of Donatello’s

Campanile prophets upstairs), and to see the full effect of Donatello’s composition you have to

bend down, or kneel. Looked at head on, the

composition does not even make sense (the torso is too long, the drapery too

complicated, and the position and expression of the face isn’t comprehensible),

while viewed from below it resolves into a powerful and stable triangular

composition in which the torso shortens and assumes a meaningful structure and

the folds of the drapery over the knees take on shape and direction, and the

head begins to show energy and nobility and the glance becomes purposeful. It clear that Donatello’s entire composition was adjusted to the viewpoint the

observer was meant to have in relation to the sculpture in situ. (This is particularly

important to note, not only because it demonstrates his elegant grasp of

perspective and optical effect, but because it makes an irrefutable case for

viewing his Campanile prophets from the acutely low angle they require. Upstairs I’m going to insist you actually

need at least to sit on the floor—if not actually lie down!—

in order to view the works properly.) The result is a figure whose dignity and

sense of purpose is clear: as

Mezzanine: Half way up

to the second floor is Michelangelo’s Pietà

(ca. 1550), originally designed for his own tomb. The story goes that Michelangelo smashed the

work, which was later reassembled by a pupil, who completed the figure of Mary

Magdalene.

Second

Floor:

Main

Room - Donatello:

IMPORTANT: The four statues of prophets (and the Abraham and Isaac) made for the façade of the Campanile (the first

five in the following list) must be viewed from sharply below in order

to see them as Donatello meant them to look! As you saw from the placement

of the copies on the Campanile itself, they were positioned very high up

(~10 meters), and, as discussed in describing the St. John the Evangelist (q.v.,

above), Donatello clearly

took the angle of viewing into account in his plan of these figures. They simply do not compose properly viewed

head on. You actually need to sit

down on the floor to view them.

This is not an exaggeration—if anything, it is an understatement: it’s probably best to lie on the floor

to view them (although a bit awkward)!

(Try for yourself the comparison of looking at them head-on with viewing

them from below.) Sitting actually

allows you to spend the time to take them in more fully, too. Do not neglect to move to a position 30-40º to

either side of each statue, as well as head on in order to see the full

richness of what he has created. If you have hesitation about

spending that much time on the floor, do it at very least for the two most extraordinary

of these work, Lo Zuccone

and Il Popolano (q.v., below). To make the point, in the section below I

juxtaposed two similar photographs of Il

Popolano, the one taken from below, and the other head-on—and if

that doesn’t convince you to get down on the floor, nothing will!

Beardless Prophet: (1416-18) The earliest of the

prophets. The head is particularly

interesting: it clearly is based on

classical Roman portrait types, but it also has an extraordinary level of

individuality and of realism in the portrayal of age and suffering—yet not

without firmness and resolve. Donatello at this early stage in his

career is beginning to explore the realism of physical and psychological

experience, in a way that is to reach fruition in Lo Zuccone and Il

Popolano (q.v., below). The hands are also marvelously

strong—particularly the right hand, with which the prophet insistently points

to the scroll containing the message he has been

charged to deliver. It has been

speculated that the weaker drapery of this figure is attributable to its having

been executed by Donatello’s

assistant Nanni di Bartolo, known as Il Rosso.

Bearded Prophet: (1418-20) This figure is far

more pensive than its slightly earlier companion, yet it lacks none of its

power. There is the suggestion that this

prophet is someone who has faced adversity; yet the monumentality and a

nobility of the form, reflected in the power of the drapery, reassures us that

he has not been shaken in his resolve.

There is an unmistakable individuality and vivid personality in the

face.

Abraham and Isaac (done with Il Rosso): (1421) While the design of this piece was

certainly Donatello’s, the execution

was done in part by his assistant. The complex,

intertwined composition must be Donatello’s. In this piece, the height of the dramatic

moment has passed. Unlike Brunelleschi’s competition panel of

this scene, which captures the very highest point of the tension and drama,

here the tension is beginning to relax:

Abraham’s right arm is starting to slacken, and the knife is slipping

away from Isaac’s throat; Isaac is in a state of passive acceptance; the angel

has come and gone. Nevertheless, what

remains is the close, human contact of this father and son, with nothing to

mitigate the immediate implications of what Abraham had been about to do. Abraham’s pained expression gives the

impression that he is well aware of the horror of the deed he had been about to

commit.

These next two, Lo Zuccone and Il Popolano, are perhaps my

two favorite sculptures in the world! Again,

I remind you that they must be viewed from sharply below in order to see

them as Donatello meant them to appear.

Lo Zuccone (?Jeremiah?): (1423-26) The reason for the question

marks in the title of this and the next prophet relates to the fact that there

is a controversy as to which is which.

The descriptive names, Lo Zuccone (“The Pumpkin-head”) and Il

Popolano (“The Man of the People”), are not in dispute, but the names of the

prophets they represent are, as are the dates which apply to each. (The Habakkuk [as referred to in the

records of the time] is the later of the two works, but it is not clear to

which of the actual statues this name—and therefore this dating—applies. I have chosen to list and date them as Janson

and Seymour do; but this is not conclusive.

Traditionally, the opposite view is held to be true—and that is how they

are labeled in the Museo del Duomo.) So

I’ll stick to using the descriptive names for practical purposes. Here, then,

is a photo of Lo Zuccone:

Il Popolano (?Habakkuk): (1427-35) To make the point that these statues must be

viewed from below, I have here juxtaposed two similar photographs of Il Popolano, the one on the

left taken from below, and the one on the right head-on:

You will note that when viewed head-on, the body of

the prophet dissolves and loses its strength and three-dimensional presence;

the drapery becomes shallow and loses its power; and the intensity of the left

hand and the statement it makes clutching the scroll of the prophet’s message

all but disappears. Having made this

point, though, I encourage you to focus only on the photograph on the left.

By

your leave, I am here going to quote from my undergraduate dissertation, Donatello

and the Tragic Sense of Life.

(Please pardon my 21 year-old prose, which itself

is now more than four and a half decades old!):

Donatello most fully realizes the tragic potential of the prophetic theme in his last two prophets, Il Popolano and Lo Zuccone. In these two figures Donatello embodies all the powerful human drama of tragedy.

Il Popolano is a strong-willed, determined man who faces

his task with unswerving directness. Donatello has depicted him in the very

act of delivering his message: in his

left hand he clutches the scroll which contains that message. This is not a scroll which he displays, as

did the Beardless Prophet. That

earlier prophet was cast as a Roman orator, and his scroll was a formal device

of rhetoric, used by him as a prop. The

scroll of Il Popolano is not something he uses visually to inspire his

audience; on the contrary, it is something from which he draws his personal

inspiration. This scroll is his own little fragment:

it is a humble document, crumpled from long use. It draws its significance not from its

physical characteristics, but from the moral importance of its contents; and it

becomes an important part of the statue not through optically asserting itself

on the viewer’s senses, but through psychologically asserting itself on the

viewer’s overall comprehension of the work.

It is important to the statue because it is so greatly important to the

prophet. The scroll symbolizes the

message to which he has chosen to devote his life. He faces his people to propound that message,

holding his scroll before him almost as if for moral support.

It must be remembered that the message of the

prophet was never an easy one for his audience to accept. The Old Testament prophet had a message that

was primarily moral and a role that was essentially that of social reform. His was the difficult task of convincing his

fellow men of their injustice and iniquity.

Moreover, he had to get them to change their ways. People are never readily convinced that they

should change. Thus the work of the

prophet was always met with much resistance.

Il Popolano would appear to react angrily to the

resistance he meets in propounding his message. The intense furrow of his brow, his tight

frown, the tensed muscles of his face, the strained sinews which stand out on

his neck—his expression reveals an angry disapproval, not only of his people’s

iniquity, but also of their blindness.

He has tried to warn them, and they have not accepted his message.

Il Popolano looks angrily away from his people. His gaze is off to the left and up—above the

heads of his audience. He averts his

gaze not to ignore his people and become introspective, nor to turn to an

ascetic mysticism by withdrawing from the demands of the situation, but rather

to gather his energy for another volley.

He is disgusted with his people and his entire figure reflects the

tension of his anger: the muscles of his

right arm are tense and strained, causing the veins to stand out sharply; his

right hand is angrily pressed so hard against his thigh that it gives energy to

the powerful undulations of drapery that seem to spread away from this gesture

as ripples spread from a disturbance on water.

Nevertheless,

he will not abandon those who have caused this anger. The determination in his gaze is as obvious as

the anger, and in his entire figure one feels a solidity that reflects his

resolve. His strong conviction obviously

will triumph over those feelings which try to shake it. He looks away to regain his composure, but he

will again return to his task. He faces

great adversity, but he will never yield to that adversity.

There is in Il Popolano a powerful realization

of the tragic implications of the role of the prophet. In it one can see what it means, in human

terms, to devote one’s life to propounding a message that people do not wish to

hear. One feels with the prophet the

anger and frustration of being rejected by the very people to whom he has

dedicated his life. One feels the

suffering of a man who is willing to step outside the system and question

accepted norms. In the fiery spirit of Il

Popolano, Donatello seems to

have recaptured something of the Old Testament, tragic concept of the prophetic

life.

Il Popolano—as Lo Zuccone— is a work of art that is imbued with psychological complexity,

intense emotion, human nobility, and a view of the world—and of human action

within it—that is radically different from everything which has gone before

it. Allow yourself to stand (or, more

correctly, sit) it awe of it.

Mary

Magdalene: (1454-55)

This wooden statue once stood in Il Battistero; but, after having been

terribly damaged in the flood of 1966, it was moved to the Museo del Duomo. It has been

extensively restored and painted–and finally it again looks like I originally

remember it. It is still a striking

work, however: the harshness and extreme

suffering so clear in this haggard creature was a major departure for Donatello, and was said to have evoked

a large degree of religious fervor in those viewing it. It has even been suggested by Janson that it

foreshadows the shift towards such fervor that ultimately culminates in the

ascendancy of Savanarola, whose turning away from the rationality of the

Renaissance towards older religious fundamentalism marked the later years of

the quattrocento in

Cantoria: (1433-39,

over the statue of Mary Magdalene) This was probably really an organ

loft. It is by Donatello, and it is a brilliant work, although it is not the part

of his talent I am most interested in.

Main

Room - Work of others:

Cantoria

by Luca della Robia: (opposite one by Donatello)

Even less interesting than Donatello’s.

Sala

delle Formelle: (“Room

of the Panels”)

Eight

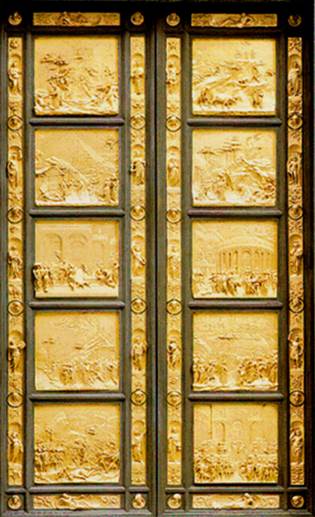

Panels from Ghiberti’s “Gates of Paradise”:

(1424-52) All ten of the recently

restored, magnificent gilt bronze reliefs Ghiberti

did for the East Doors of Il Battistero are now assembled in a

climate-controlled display on the first floor of the museum.

(For over 30 years, there

were four on display and the rest were “undergoing restoration”; and another

four reappeared 8 years ago; now, finally, the project has been completed!) Each panel is

a square, in contrast to the Gothic quatrefoil form used for the other doors of

Il Battistero. The original plan called for 28 panels, as in the two other sets

of Baptistery doors, each with an Old Testament story; but Ghiberti reduced the number of panels to 10, combining multiple

segments of these stories on each panel.

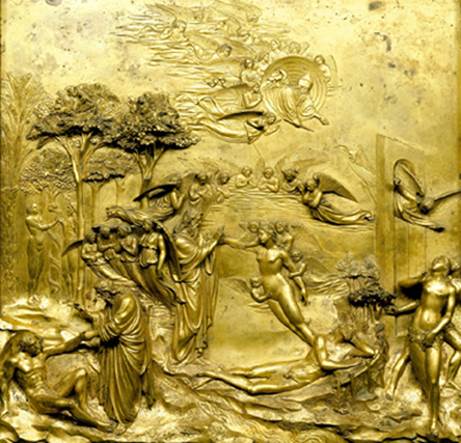

In the Cain and Abel

relief, he combined five separate elements:

Cain at Work, Abel at Work, the First Parents at Work, Cain

Killing Abel, and God Cursing Cain. In the beautiful Adam and Eve relief, he combines what was

to have been three separate reliefs: The

Creation of Adam, the Creation of Eve, and The Expulsion from Paradise.

All

ten of these reliefs are truly beautiful sculptures, although Ghiberti never quite makes the transition into the

Renaissance—and his attempt at these more Renaissance forms lacks the power and

success of his earlier competition panel, done in a more Gothic style. Ghiberti

included a self-portrait among the other details in the border surrounding the

reliefs:

The

room off the other side of the Main Room: This room is full of very interesting

architectural details, mostly from the façade of Il Campanile.

Orsanmichele: In the center

of

Cappella

Brancacci (Brancacci Chapel) in Santa Maria

del Carmine: {Monday-

Saturday 1000-1700; Sunday 1300-1700; closed Tuesday} (the entrance is through

a door to the right of the façade of the church; there had been a fascistic and

ridiculous system imposed on visitors, which, at least for this visit in May

2013, was no longer being enforced: you waited for ~15 minutes until you were

allowed to go in through the cloister to the ticket office, where you bought

your ticket and then had to wait another 15 minutes until you were allowed into

the chapel, where you were allowed exactly 15 minutes to view these magnificent

frescoes. It was truly absurd, and, had

it not been for the importance and beauty of the art, I’d have refuse to consider doing it.

Thankfully, this was not the case on this visit, and we were able to

spend unlimited amounts of time luxuriating in the presence of these incredible

frescoes. Nevertheless, I am unhappy to

report that the signage still suggested that this regime may be imposed when

there is a higher volume of visitors to the Chapel.) This chapel is in the “Oltrarno” (“other side

[of the Arno]”—i.e., the ‘left bank’), in the otherwise entirely uninteresting church of Santa Maria del Carmine.

The Cappella Brancacci contains some of the greatest paintings of the

Renaissance. The fresco cycle,

essentially about the Life of Saint Peter,

was begun in 1424 by Masaccio

working together with Masolino. There was an obvious collaboration on the theme and

plan of the cycle—and they divided the space up so there was to be a pattern of

interspersal of their individual works. Masaccio left the project unfinished to

go to Rome in 1427 or 28; and some of his frescoes were completed later by Filipino Lippi.

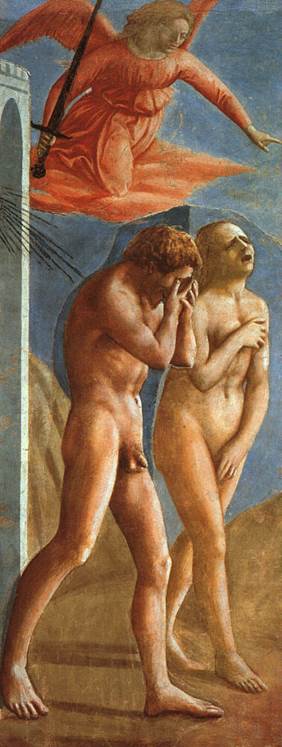

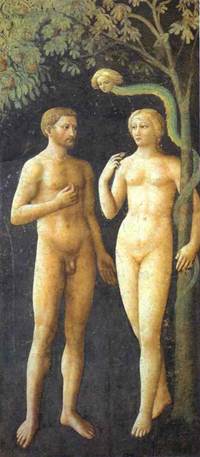

The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden: The first of

the great contributions of Masaccio,

on the top left of the chapel as you enter.

This fresco captures the essence of the Renaissance spirit: man, even as sinner, has unlimited dignity

and stature. There is a strength and

monumental presence in the form of these figures—not to mention a classical

beauty. They,

and Eve in particular, capture the full extent of pain and suffering in the

human condition.

Masaccio captures emotion and dramatic intensity to an extent

unparalleled by other painters of his day—but very akin to the spirit captured

by Donatello. Note also the composition: the fiery red angel above pressuring them out

of the Garden with the weight of his powerful gesture and creating the movement

at the heart of the theme. (cf., the

Temptation of Adam and Eve [below] by Masolino,

opposite: a wonderful work, but with

none of this humanistic emphasis.)

The Tribute Money: (immediately

to the right of the Expulsion) Here Masaccio presents three separate moments in the story: in the central space, the tax collector makes

his request and Jesus replies with directions to St. Peter; to the left, Peter catches the fish and takes

the coins out of its mouth; on the

right, Peter hands the money over to the tax collector. (It has been suggested that the theme was chosen and

presented this way to help elicit support for the collection of a new tax in

Note

carefully: the classicism of pose and

the sculptural monumentality of the figures; the individuality and emotion in

the faces (look especially carefully at these [the head of Jesus in the center

of this work is shown below]);

the

perfect use of linear perspective in the architectural elements, combined with

the painterly creation of space in the landscape in the background (cf., the similar

combination in the relief panel Donatello

did for the St. George now in Il

Bargello); and the beauty of that

landscape, itself.

The

Raising of the Son of Theophilus and Enthronement

of St. Peter: (directly below the Tribute Money) This fresco was

most probably designed by Masaccio, although

there are many hands involved in the execution.

In

the Enthronement scene

(at the right of the work), it is clearly mostly Masaccio—particularly the magnificent St. Peter (below)

|

|

|

and the

four figures at the far right (which are actually portraits of [from left to right] Masolino, Masaccio, Alberti, and Brunelleschi, with the self-portrait

of Masaccio facing out at the

viewer).

|

Other

stuff by Masaccio: Most

authorities believe The Baptism of the Neophytes (above, to the right of the

window; shown below) is by Masaccio;

Similarly, the one of St. Peter Healing the Sick with his Shadow (to the left of the

window, below).

Most

of the rest is by Masolino, with

some later work by Filipino Lippi (e.g.,

St. Peter in Prison—under the Expulsion, on left); all far less

interesting than the astounding works of Masaccio.

Santo Spirito: {8:30-12, 4-6; closed Wed. afternoons} This church is the culmination of Brunelleschi’s development. It was commissioned in 1434